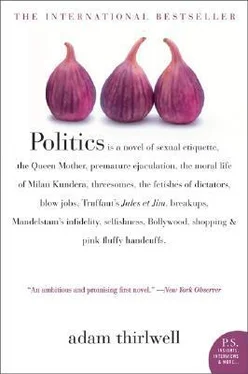

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Moshe was wishing he had not said it was a great role. He was wishing he had just agreed with her.

He backtracked.

‘It’s true,’ said Moshe. ‘I mean, the play does turn class into fashion. It romanticises class.’ The duo paused. The conversation paused. Neither of them understood. Moshe certainly did not understand. He swayed. He steadied himself. Nana looked at her empty champagne glass.

Pauses are very difficult. They require agility. Unfortunately, neither Moshe nor Nana was being agile.

Moshe nervously added, ‘I mean isnit just propaganda by deed?’ as Nana responded, in slow motion, repeating, ‘Romanticises class.’ Moshe lowered his eyebrows and pushed his lips forward to show her that he was troubled, intellectually. Then Moshe looked sideways at Papa.

Papa was chatting to Anjali about the racial politics of acting. He was promising reforms.

And that was the beginning. That conversation was the beginning of the romance of Nana and Moshe. But Nana hadn’t noticed.

It is a pity, Nadezhda Mandelstam would have thought it was a pity, but as Nana returned to Edgware with Papa, she was not thinking about Moshe. She had almost forgotten him already. She was thinking about theatres.

Theatres nonplussed her.

There was the foyer. Relaxed in the foyer, Papa had chatted, his neck angled up to the taller fat men. And Nana listened to him, while she looked with compassion at the boy with a plastic box of programmes and Loseley Dairy ice cream harnessed to his neck. With compassion, Nana noticed how his gelled precise fringe draped over some acne.

And then the auditorium, the pretentious auditorium. She watched the small lights in the rig dim down. In husky whispers, people almost finished their conversations. While Nana counted the white fire-exit arrows, and then the white running men on green backlit backgrounds.

Papa taptouched Nana’s right hand. He told her to put on her glasses, tucked up on her lap. He grinned at her.

And then the star arrived on stage, disguised as Prince Paul Maraloffski. His name was something, Moshe something, Papa muttered to himself, chinking the open programme towards the safety lights. Moshe, the socialist socialite, drawled his readymade jokes. ‘In a good democracy, every man should be an aristocrat.’ No one laughed. Prince Paul Maraloffski intoned his epigrams. ‘Culture depends on cookery. For myself, the only immortality I desire is to invent a new sauce.’

Nana considered the ending of Vera, or the Nihilists. She was amazed by its sentimentality. Vera, tortured by love, saves Russia but kills herself. And Nana had turned to her dearest Papa. She hoped that he was smiling too.

Papa was not smiling. Papa was an angel. He was moved by the ending. He was, thought Nana, almost crying. But because she was a girl who cared about her Papa, she cared for him more than anything, Nana was not embarrassed by this. No, she just tried to look after him. ‘It’s okay, Papa. Sokay,’ whispered Nana. ‘Don worry. She’s still breathing.’

Nana just didn’t get theatres.

12

When Anjali went home, it was around midnight. She lived in a flat in Kentish Town with her brother. Her brother was called Vikram. You are never going to see Vikram in this story. But I am mentioning him just now in case you are worried. He is there to reassure you that Anjali was not a loner.

Anjali went into the kitchen and looked in the fridge. Then she closed the fridge. She took off her denim jacket and sat on the sofa in the living room. She got up for a piss. She came back to the kitchen and opened the freezer. She took out a small cardboard pot of Ben Jerry’s Phish Food ice cream. She opened it and left it on top of the freezer. Then she sat on the sofa and picked up a bulldog-clipped pile of papers, which were Anjali’s copy of a new script by Gurinder Chadha. She almost read through her fourteen lines. A telltale sign that she did not do this was that she did not open the bulldog clip. She looked at the letter requesting Ms Sinha to accept this working copy. She sat. She stared at the blank TV.

She remembered the ice cream.

She got up and took a spoon out of a drawer. The ice cream was still solid. She returned to the sofa anyway with the ice cream and the spoon. Anjali prodded at the ice cream, bored. She licked the spoon. She tumbled to her hands and knees and got out a video, sent to her by her mother, of Sholay. She considered watching a four-hour film. She mused on how much she disliked serious Bollywood films. She only liked the frivolous ones. She laughed at her mother’s taste, out loud. Laughing out loud made her feel weird. She pushed the video into the machine and pressed play. She turned on the TV and found channel 0.

She missed her ex. She missed Zosia.

She remembered going to the Belle Vue cinema in Edgware to the late-night Hindi films. The Belle Vue cinema was located close to Nana and Papa but Anjali did not know that yet. Anjali’s family lived in Canons Park and they went to the flicks together. She wondered why they had always called them flicks. She remembered how she fancied Madhuri Dixit more than she fancied Amitabh Bachchan. She remembered them all eating samosas in the Belle Vue cinema, and her mother stuffing a ticklish paper napkin down Anjali’s T-shirt. Anjali remembered her fondness for little comic Johnny Walker. She remembered Johnny in Guru Dutt’s Mr Mrs ’ 55 , especially the hit song ‘Dil Par Hua Aisa Jadu’, in which Johnny listens to Guru Dutt in love, from a bar to a bus stop to a bus to the road. Or there was Madhuri Dixit in Devdas, a diamond-shaped gold ingot pressed between her eyes. Anjali considered whether Bollywood masala films were a little untechnical. Their appeal was not exactly formal.

Anjali was a mildly successful actress with a mildly unsuccessful love life.

This is not a very strange set-up, I think.

After all, sex isn’t everything.

II

3. They fall in love

1

Nana fell in love with Moshe on 28 April.

That was Moshe’s theory. That was the date he remembered. On that day, thought Moshe, his performance in the living room had made Nana swoon.

This might not seem very plausible. And it was not very plausible. When you know what his performance was, it will seem especially implausible.

They were in Moshe’s Finsbury flat. It was on the first floor of a Victorian house. And Moshe announced the cushion shtick. ‘The what?’ said Nana. ‘Oh the cushion trick,’ said Moshe.

This was the cushion trick. Moshe pushed the window open and then picked up a cushion. His grandmother had embroidered it with a large red velvet heart. He hugged the cushion. He cradled the cushion round the room. Moshe cooed and kissed, he tossed his baby up and caught it. The cushion’s gold tassels flapped. Nana stared at Moshe. He was in paternal bliss. But then suddenly and tragically the bubba slipped from Moshe’s hands and tumbled out the window, clumping on the pavement. It lay there beside an empty box of Heineken. While Moshe mouthed his misery, keening for his child.

Obviously this could not have been the moment that Nana fell in love with him. There is never a climactic moment. And even if there had been, I do not think this would have been the one. But that was Moshe’s conclusion. He concluded that his talent had charmed her.

This does not mean that Moshe was not talented. He was a good actor. It was just not his talent that charmed her.

You see, when Moshe showed off his cushion trick or shtick, Nana was not even watching. Well, she was watching but not concentrating. Instead, she was wondering why she was there, on a Sunday afternoon, with her MA thesis due. She was especially baffled because Moshe was behaving so oddly.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.