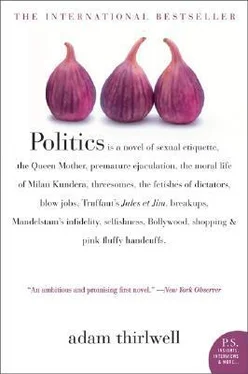

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sometimes he felt loyal. But, more often, he did not. He did not understand allegiance. When Papa at one point got sad about the trial of SS Lieutenant-Colonel Adolf Eichmann, Moshe agreed it was sad. It was sad, said Moshe, that there had been such a flagrant miscarriage of justice. But this was not why Papa was sad. Papa did not agree that the real person who should have stood trial was the maniac Nazi-hunter, Simon Wiesenthal. That was just Moshe’s opinion.

No, Moshe did not have an easy relationship with Judaism.

For example, Moshe owned a 1996 Union of Jewish Students Haggadah. I also own this book. The Haggadah outlines the correct procedure for the Passover service. Imitating Hebrew, the UJS Haggadah begins at the back. You read it back to front. I think this is an affectation. Moshe also thought it was an affectation. Anyway, in this book, there is a section called ‘Why Be Jewish?’ The impetus for this section came from the chief rabbi of Britain, Dr Jonathan Sacks.

One of the illustrious Jewish figures interviewed — and these figures are illustrious, they include Kirk Douglas, Uri Geller, Roseanne, Steven Spielberg and Elie Wiesel — was the talkshow hostess Vanessa Feltz.

This was Vanessa Feltz’s answer to Dr Sacks’ question ‘Why Be Jewish?’ And, I have to say, at this point in his sceptical analysis of Judaism, I think I agree with Moshe. Both Moshe and I thought Vanessa’s answer was a little unbalanced.

Intermarriage robs us of our future. It callously dismisses as not worth preserving the 5,000 years of scholarship, persecution, humour and optimism which have made Jews an extraordinary people. Every marriage of Jew to gentile erodes the foundations which make us who we are. After all, without Jewish children there is no Jewish posterity. From my three-piece suite in Finchley, that feels like a tragedy.

Vanessa Feltz! Cuddly Vanessa Feltz! Two years later, in 1998, her Jewish husband left her. And Vanessa turned to another man. This man was not a Jewish man. Obviously, I approved of this miscegenation. And when the non-Jewish man left Vanessa Feltz, I did not approve. I worried that this mishap would put Vanessa off goyim for ever.

7

And what about Anjali? Was she more distressed by her ethnicity? Was British Asian Anjali vexed by the mix-up of her heritage? No. She was not. Well, she was not distressed. She cared much more about films.

But even films can be ethnically problematic. There was the time that Anjali and her schoolfriend Arjuna went to see Spike Lee’s biopic Malcolm X when it came out in 1992. They saw it at the Staples Corner multiplex. No one in the audience was white. No one in the audience was strictly black, either. At least, they were not African Americans like Malcolm X. They were all like Arjuna and Anjali.

This embarrassed Anjali. Well, it was not this precisely that embarrassed Anjali. It was not the audience. It was the audience’s attitude. Inexplicably, they all identified with Malcolm X. And this seemed silly. Surely you could like the film without thinking you were Malcolm X? thought Anjali. As they walked out of the Staples Corner multiplex, Anjali looked at Arjuna. She liked him. It wasn’t that. It was just that in his navy-blue-rimmed glasses, with a small panda on each arm to indicate that the purchase of these glasses had gone some way to support the World Wide Fund, Arjuna did not seem like a Black Power freedom fighter. He seemed even less like a Black Power freedom fighter when his father arrived — in a white Mercedes with walnut veneer — to take them home to Canons Park.

Anjali could not understand it. Malcolm X was just a mediocre film. All she could remember was a 360-degree pan round Malcolm X in his hotel bedroom. That was the only significant shot.

But there was a complication, it is true. Get her on ethnicity, and Anjali could be touchy. She might not admit it, but Anjali was touchy. For instance, the only thing Anjali liked about India was Bollywood. And Anjali’s love of Bollywood had a very simple explanation. Bollywood was un-Indian.

Un-Indian? Bollywood un-Indian? Well yes, because, for Anjali, India was cows. India was scaffolding and mud. India was full of families. Whereas a sentimental and musical film was the opposite of a family. Bollywood was Hollywood.

Classified according to some as a Second-Generation Non-Resident Indian, and according to others, including Anjali, as a resident UK citizen, Anjali enjoyed the masala flicks. She read with amused interest an interview with Shyam Benegal, who told the devoted readers of CineBlitz that the ‘current interest in us is all down to the diaspora. Without them, no one would be paying any interest.’

I think Shyam’s word ‘diaspora’ is a bit odd. A diaspora is a people driven from its homeland. And India may have been cows and mud but cows and mud do not drive you from your homeland. Shyam was being a bit melodramatic. By ‘diaspora’, he meant Indians living abroad.

Anjali also thought that this word ‘diaspora’ was odd. She was not a diasporee. Educated on scholarships at North London Collegiate School and then Brasenose College, Oxford, Anjali was just a success story. She had nothing to do with exile.

Bollywood films were the opposite of diaspora. That was their appeal for Anjali. They had nothing to do with a homeland either. They were all about style.

Perhaps you think that Bollywood films have no style. Perhaps you think they are kitsch. Well, style is arguable. The crucial thing is this. If Anjali ever liked something Indian, she liked it for un-Indian reasons.

8

Actually, Anjali is often confusing. That is one of the reasons I like her. She is unpredictable. For example, it is not just Anjali’s ethnic identity that is confusing. Oh no. It is also her sexual identity.

On Old Bond Street, Nana was being a blurry reflection beside the reflected blur of Anjali. They were admiring some Tanner Krolle luggage in a window. The luggage was pink.

Anjali said to Moshe, ‘Look Mosh, look, it’s so pretty.’ And Moshe made a noise, he made an agreeing noise. He was not thinking about fashion. He was thinking about kissing Nana. But his mouth felt wretched from a recent Starbucks skinny latte. This made him stop wanting to kiss her. So he swayed his hips against her instead, hugging her from behind and nuzzling on her shoulder.

He said to Anjali, ‘Nos pretty as you.’ Then he smirked.

To Anjali? He said that to Anjali? Yes, yes. He was jokily flirting.

And Anjali smiled back. She was flirting too.

9

Oh shopping. Oh fashion.

Some people adore fashion simply because it is so expensive. This is not a likeable position. Luckily, it is not a position anyone admits to. Other people adore the workmanship, the craft of fashion. I rather like these people. These people are similar to the people who look at clothes as artworks. For them, clothes are aesthetic. They are opportunities to exercise technique. I have to say, I am not sure I ever really believe these people. I worry that these people secretly just adore fashion because of the expensiveness. You can never quite be sure. But basically I like them.

Then there are the people who care about fashion in an abstract, magazine kind of way because they want to be hip and I really do not get those people.

And then there are people who despise fashion. They despise it because it is far too expensive. Or because it is materialistic. Or because it is really just ugly, or impractical.

Me, my attitude is a technical interest and respect combined with an amazed sarcasm. That is the unimpeachable position.

Among the three of them, there were different attitudes to fashion. And you need to know this because, at this point in the story, Nana and Moshe and Anjali were window- shopping on Old Bond Street and along Savile Row. They did not quite know how they had ended up there, but that is where they were now. They were in the heart of London’s fashion world.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.