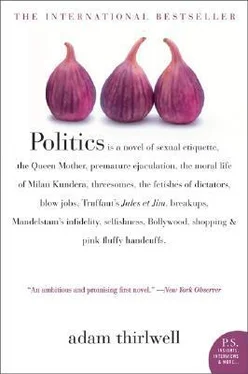

Adam Thirlwell - Politics

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Adam Thirlwell - Politics» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Politics

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Politics: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Politics»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Moshe loves Nana. But love can be difficult — especially if you want to be kind. And Moshe and Nana want to be kind to someone else.

They want to be kind to their best friend, Anjali.

Politics

Politics — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Politics», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Blumenthals were noble. They had both survived the concentration camps. But also they were racist. They disliked blacks. And this, obviously, stymied Papa. He did not know what to think. The Blumenthals confused him. They were noble and despicable.

No question, the Blumenthals were tricky. They were morally ambiguous.

‘And the girl?’ said Mrs Blumenthal. ‘How is Nina?’ ‘Nana,’ said Papa. ‘Nana,’ said Mr Blumenthal. ‘She has got a new boyfriend,’ said Papa. ‘That is good, a boyfriend,’ said Mr Blumenthal. ‘And what is this one like, the boyfriend? I do not think he will be good enough.’ ‘He’s an actor,’ said Papa. ‘He is not good enough,’ said Mr Blumenthal. ‘And I think he’s Jewish,’ said Papa. ‘Then he is certainly not good enough!’ shrieked Mrs Blumenthal, finding her joke snortingly funny.

Papa managed a giggle. It was all just too bewildering, this constant unserious humour.

Me, I like that humour very much. But then, I am not kindly. I am not sweet. I am not sweet like Papa.

4. Romance

1

In1963 mymother went to Prague on a school trip. In Prague, she stayed with a Jewish girl called Petra.

In fact, Petra was only half Jewish. Her mother was Jewish. When the Nazis occupied Prague, they informed Petra’s father that he had to leave Petra’s mother. He did not. So they sent him to the concentration camp at Terezln. They sent Petra’s mother too. And they both survived. This was obviously quite unusual. Not many people survived Terezln. To celebrate, Petra’s mother and father decided to have a second child. This child was Petra.

There were not many Jews left in Prague, after Terezln. Because of this, Petra felt particularly curious about Jewishness. So when she agreed to participate in a school exchange, she requested a Jewish girl. That was why my mother stayed with her. My mother is Jewish too.

Afterwards, Petra and my mother wrote to each other regularly. In 1968, after the Russians entered Prague, Petra came to London. She lived with my mother’s family. A year later, however, the Russians announced that all Czechs living abroad had three weeks to decide if they wanted to come back. If they ever wanted to see their families again, they would have to come back now. And she went back.

Here are two facts about Petra. She never joined the Communist Party. That is the first fact. The second fact is this. She preferred Vaclav Havel’s plays to the novels of Milan Kundera because Kundera left Czechoslovakia in 1975 and this was a betrayal of the resistance.

But Petra’s decision to return in 1969 was not motivated by commitment to the resistance. Nor was it motivated by belief in the Communist cause. In 1969 Petra went back because a boy in London had broken up with her. That was why she returned. She always believed, however, that she went back because she could not abandon her family. She could not abandon her Jewish heritage. She had to do the good thing, the right thing. That was Petra’s rationale.

But there was also a less romantic, more financial explanation. In London, Petra was working as a temp. In Prague, Petra’s mother had negotiated a job for her in the American embassy. It was salaried. It was very well salaried. With this salary, Petra could afford a house in the old Jewish Quarter. And Petra had always dreamed of a house in the Jewish Quarter. This was not quite for religious reasons either. It was because she loved art nouveau. You see, Petra — who wore stonewashed narrow-leg jeans, skyblue polyester socks and black pumps with snakeskin-effect uppers — longed for style. She adored the tracery of the balustrades in the Jewish Quarter, the floral moulding round the ceilings.

Petra went back, then, for two reasons. Neither was the obvious reason. She returned to Prague because of her love of early-twentieth-century interior decoration, and also because she had been dumped.

2

‘Yeh yeh, yeh, yeh yeah,’ said Anjali. ‘You love that?’ said Nana. ‘You really?’ ‘Yeh yeah,’ said Anjali. As she said this Anjali swept a rhetorical hand and knocked an empty glass that had once held a vodka tonic. It wobbled then luckily steadied.

Have I described what Anjali looks like? I do not think I have. Well, I’ve described her make-up, but not her clothes.

Anjali was slimmish, shortish, darkish. Her style was a mixture of clubby and sporty. A normal outfit for Anjali was her old denim jacket, which she had worn since she was fifteen, and a pair of red Perry Ellis trainers with black stitching. She had a small collection of freckles across her nose. She often wore a silver bangle on her wrist. There were pale lilac acne scars on her cheeks. Halfway down her back, on her spine, there was a mole.

Eventually, Nana would be bored by this mole.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

‘I think that sometimes Mies is a little bit, a little bit too programmatic,’ said Nana. ‘Like his skyscrapers?’ said Anjali. ‘Oh no those are wonderful,’ said Nana. ‘Oh good,’ said Anjali. ‘They’re so austere,’ said Nana. ‘I love that skyscraper, the Friedrichstrasse skyscraper, it’s so beautiful,’ said Anjali. ‘The building all made of glass?’ said Nana. ‘Yeah that one,’ said Anjali. ‘Oh yes, that’s beautiful,’ said Nana.

As you can see, they were talking architecture. They were being highbrow. And Moshe was there too. It was just that he was not included in this discussion. He had disincluded himself. A slump on the red leather sofa, beside a two-foot test tube full of crumpled white lilies, Moshe was being quiet. Instead, he was getting his money’s worth, eating Ј6.50 of Japanese mixture graciously provided in a white china bowl by the proprietors of mybar, in myhotel. Although not mine, thought Moshe, not fucking mine. It was not his idea to price a my mary at Ј6.50. It was not his personal price range.

He carried on eating, in crunchy munchy silence.

While Anjali and Nana got to know each other.

Nana said, ‘I think what’s intresting is how form is inter- naschnal. I think they were right, calling it the Inter- naschnal Style. I mean I think people think that with, with with, with the Bauhaus it’s all specific to Berlin. But then Mies van der Rohe goes to New York and he does the same designs. So it had nothing to do with Berlin. It was all to do with form.’

Anjali nodded. She rather liked being taught. She rather liked Moshe’s new pretty girlfriend and her difficult monologues. It was fun that this girl was clever.

‘But what about the roofs?’ said Anjali. ‘What do you mean?’ said Nana. ‘Well I thought there was some German reason for them,’ said Anjali. ‘Oh, designing buildings with flat roofs? Being anti pointed roofs?’ said Nana. ‘Yes,’ said Anjali. ‘Oh I think that’s terrible,’ said Nana. ‘I hate that. It was all to do with Communism,’ she said. ‘With Communism?’ said Anjali. ‘They thought pointed rooves were like crowns,’ said Nana. ‘So they made their rooves flat.’ ‘Because of crowns?’ said Anjali. ‘Don’t,’ said Nana.

‘But’, said Anjali, ‘what about when it rains? What about that?’ ‘Oh no exacly,’ said Nana.

Nana nodded. She rather liked this girl. She rather liked Moshe’s pretty friend. It was fun that this girl was clever.

Nana said, ‘Mies also refused to let the blinds be uneven. He refyoosed. They were either up or down, he wanted. On the Seagram Building, in New York. The skyscraper. And then all the people inside complained. So Mies compromised. He added another position. So it was up or halfway or down. I mean.’

‘Only three positions?’ said Anjali. ‘Oh I know,’ said Nana. ‘I know.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Politics»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Politics» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Politics» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.