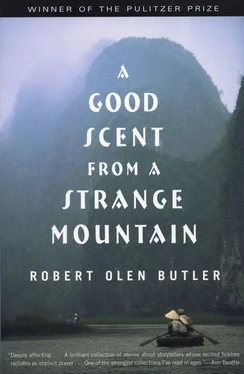

I look at the gate in our white picket fence and soon your father will come through. I want to tell you that you are a lucky girl. Even as my tears change. B  o and I were betrothed to be married. And then he was called into the Army and he went away before the ceremony could be arranged and he died in a battle somewhere in the mountains. The gate is opening now and your father, my husband, is coming through and he is a good man. He keeps this fence and our house free from the mildew. He scrubs it with bleach and hoses it every six months and he stops at my hibiscus, not seeing me here at the window. I must soon stop speaking. He is a good man, an American soldier who loved his Vietnamese woman for true and for always. He will find me by the window and touch my cheek gently with the back of his fine, strong hand and he will touch my belly, trying to think he is touching you.

o and I were betrothed to be married. And then he was called into the Army and he went away before the ceremony could be arranged and he died in a battle somewhere in the mountains. The gate is opening now and your father, my husband, is coming through and he is a good man. He keeps this fence and our house free from the mildew. He scrubs it with bleach and hoses it every six months and he stops at my hibiscus, not seeing me here at the window. I must soon stop speaking. He is a good man, an American soldier who loved his Vietnamese woman for true and for always. He will find me by the window and touch my cheek gently with the back of his fine, strong hand and he will touch my belly, trying to think he is touching you.

You will love him, my little one, and since I know you understand my heart, I do not want you to be sad for me. I had my night on the moon and when I came back down the rainbow, the world I found was also good. It is sad that there is no return, but we can still light a lantern and look into the night sky and remember.

Though I have never seen you, my son, do not think that I am unable to love you. You were in your mother’s womb when the North of our country took over the South and some of those who fought the war found themselves running away. I did not choose to run, not with you ready to enter this world. I did not choose to leave my homeland and become an American. I have chosen so few of the things of my life, really. I was eighteen when Saigon was falling and you were dreaming on in your little sea inside your mother in a thatched house in An Khê. Your mother loved me then and I loved her and I would not have left except I had no choice. This has always been a strange thing to me, though I have met several others here where I live in New Orleans, Louisiana, who are in the same condition. It is strange because I know how desperately many others wanted to get out, even hiding in the landing gears of the departing airplanes. I myself had not thought of running away, did not choose to, but it happened to me anyway.

I am sorry. And I write you now not to distract you from your duty to your new father, as I am sure your mother would fear. I write with a full heart for you because I must tell you a few things about being a person who is somewhere between a boy and a man. I was just such a person when I held a rifle in my hands. It was a black thing, the M16 rifle, black like a charcoal cricket, and surprisingly light, with a terrible voice, a terrible quick voice like the river demons my own father told stories about when it was dark and nighttime in our village and I wanted to be frightened.

That is one thing I must tell you. As a boy you wish to be frightened. You like the night; you like the quickness inside you as you and your friends speak of mysterious things, ghosts and spirits, and you wish to go out into the dark and go as far down the forest path as you can without turning back. You and your friends go down the path together and no one dares to say that you have gone too far even though you hear every tiny sound from the darkness around you and these sounds make you quake inside. Am I right about this? I dream of you often and I can see you in this way with your friends and it is the same as it was with me and my friends.

This is all right, to embrace the things you fear. It is natural and it will help build the courage you must have as a man. But when you are a man, don’t become confused. Do not seek out the darkness, the things you fear, as you have done as a boy. This is not a part of you that you should hold on to. I myself did not hold on to it for more than a few minutes once the rifle in my hand heard the cries of other rifles calling it. I no longer dream of those few minutes. I dream only of you.

I cannot remember clearly now any of the specific moments of my real fear, of my man’s fear with no delight in it at all, no happiness, no sense of power or of my really deep down controlling it, of being able to turn back with my friends and walk out of the forest. I can only remember a wide rice paddy and the air leaning against me like a drunken man who says he knows me and I remember my boots full of water and always my thought to check to see if I was wrong, if there was really blood in my boots, if I had somehow stepped on a mine and been too scared to even realize it and I was walking with my boots filled with blood. But this memory is the sum of many moments like these. All the particular rice paddies and tarmac highways and hacked jungle paths — the exact, specific ones — are gone from me.

Only this remains. A clearing in a triple-canopy mahogany forest in the highlands. The trees were almost a perfect circle around us and in the center of the clearing was a large tree that had been down for a long time. We were a patrol and we were sitting in a row against the dead trunk, our legs stuck out flat or tucked up to our chests. We were all young and none of us knew what he was doing. Maybe we were stupid for stopping where we did. I don’t know about that.

But our lieutenant let us do it. He was sitting on the tree trunk, his elbows on his knees, leaning forward smoking a cigarette. He was right next to me and I knew he wanted to be somewhere else. He was pretty new, but he seemed to know what he was doing. His name was Binh and he was maybe twenty-one, but I was eighteen and he seemed like a man and I was a private and he was our officer, our platoon leader. I wanted to speak to him because I was feeling the fear pretty bad, like it was a river catfish with the sharp gills and it was just now pulled out of the water and into the boat, thrashing, with the hook still in its mouth, and my chest was the bottom of the boat.

I sat trying to think what to say to Lieutenant Binh, but there was only a little nattering in my head, no real words at all. Then another private sitting next to me spoke. I do not remember his name. I can’t shape his face in my mind anymore. Not even a single feature. But I remember his words. He lifted off his helmet and placed it on the ground beside him and he said, “I bet no man has ever set his foot in this place before.”

I heard Lieutenant Binh make a little snorting sound at this, but I didn’t pick up on the contempt of it or the bitterness. I probably would’ve kept silent if I had. But instead, I said to the other private, “Not since the dragon came south.”

Lieutenant Binh snorted again. This time it was clear to both the other soldier and me that the lieutenant was responding to us. We looked at him and he said to the other, “You’re dead meat if you keep thinking like that. It’s probably too late for you already. There’ve been men in this place before, and you better hope it was a couple of days ago instead of a couple of hours.”

We both turned our faces away from the rebuke and my cheeks were hotter than the sun could ever make them, even though the lieutenant had spoken to the other private. But I was not to be spared. The lieutenant tapped me on the shoulder with iron fingertips. I looked back to him and he bent near with his face hard, like what I’d said was far worse than the other.

He said, “And what was that about the dragon?”

I was too frightened now to make my mind work. I could only repeat, “The dragon?”

“The dragon,” he said, his face coming nearer still. “The thing about the dragon going south.”

For a moment I felt relieved. I don’t know how the lieutenant sensed this about me, but somehow he knew that when I spoke of the dragon going south, it was not just a familiar phrase meant to refer to a long time ago. He knew that I actually believed. But at that moment I did not understand how foolish this made me seem to him. I said, “The dragon. You know, the gentle dragon who was the father of Vietnam.”

Читать дальше

o and I were betrothed to be married. And then he was called into the Army and he went away before the ceremony could be arranged and he died in a battle somewhere in the mountains. The gate is opening now and your father, my husband, is coming through and he is a good man. He keeps this fence and our house free from the mildew. He scrubs it with bleach and hoses it every six months and he stops at my hibiscus, not seeing me here at the window. I must soon stop speaking. He is a good man, an American soldier who loved his Vietnamese woman for true and for always. He will find me by the window and touch my cheek gently with the back of his fine, strong hand and he will touch my belly, trying to think he is touching you.

o and I were betrothed to be married. And then he was called into the Army and he went away before the ceremony could be arranged and he died in a battle somewhere in the mountains. The gate is opening now and your father, my husband, is coming through and he is a good man. He keeps this fence and our house free from the mildew. He scrubs it with bleach and hoses it every six months and he stops at my hibiscus, not seeing me here at the window. I must soon stop speaking. He is a good man, an American soldier who loved his Vietnamese woman for true and for always. He will find me by the window and touch my cheek gently with the back of his fine, strong hand and he will touch my belly, trying to think he is touching you.