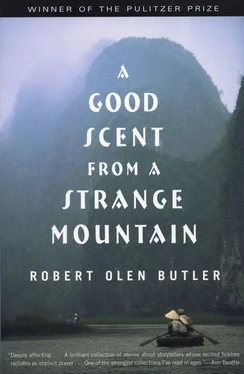

Except perhaps when I am as old as Mr. Chinh. Perhaps he, too, moved through his life as distracted as me. Perhaps only after he forgot his granddaughter did he remember his Hotchkiss. And perhaps that was necessary. Perhaps he had to forget the one to remember the other. Not that I think he’d made that conscious choice. Something deep inside him was sorting out his life as it was about to end. And that is what frightens me the most. I am afraid that deep down I am built on a much smaller scale than the surface of my mind aspires to. When something finally comes back to me with real force, perhaps it will be a luxury car hanging on a crane or the freshly painted wall of a new dry-cleaning store or the faint buzz of the alarm clock beside my bed. Deep down, secretly, I may be prepared to betray all that I think I love the most.

This is what brought me to the slump of grief against the live oak in my front yard. I leaned there and the time passed and then my wife crept up beside me. I turned to her and she was crying quietly, her head bowed and her hand covering her eyes.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“I put him in the guest room,” she said. “He thanked me as he would an innkeeper.” She sobbed faintly and I wanted to touch her, but my arm was very heavy, as if I was standing at the bottom of the sea. It rose only a few inches from my side. Then she said, “I thought he might remember after he slept.”

I could neither reassure her with a lie nor make her face the truth. But I had to do something. I had thought too much about this already. A good businessman knows when to stop thinking and to act instead. I drew close to my wife, but only briefly did my arm rise and hold her. That was the same as all the other forgotten gestures of my life. Suddenly I surprised myself and my wife, too. I stepped in front of her and crouched down and before either of us could think to feel foolish, I had taken Mai onto my back and straightened up and I began to move about the yard, walking at first, down the long drooping lower branch of the oak tree and then faster along the sidewalk and then up the other side of the house, and I was going faster and she only protested for a moment before she was laughing and holding on tighter, clinging with her legs about my waist and her arms around my neck, and I ran with her, ran as fast as I could so that she laughed harder and I felt her clinging against me, pressing against me, and I felt her breath on the side of my face as warm and moist as a breeze off the South China Sea.

I like the way fairy tales start in America. When I learn English for real, I buy books for children and I read, “Once upon a time.” I recognize this word “upon” from some GI who buys me Saigon teas and spends some time with me and he is a cowboy from the great state of Texas. He tells me he gets up on the back of a bull and he rides it. I tell him he is joking with Miss Noi (that’s my Vietnam name), but he says no, he really gets up on a bull. I make him explain that “up on” so I know I am hearing right. I want to know for true so I can tell this story to all my friends so that they understand, no lie, what this man who stays with me can do. After that, a few years later, I come to America and I read some fairy tales to help me learn more English and I see this word and I ask a man in the place I work on Bourbon Street in New Orleans if this is the same. Up on and upon. He is a nice man who comes late in the evening to clean up after the men who see the show. He says this is a good question and he thinks about it and he says that yes, they are the same. I think this is very nice, how you get up on the back of time and ride and you don’t know where it will go or how it will try to throw you off.

Once upon a time I was a dumb Saigon bargirl. If you want to know how dumb some Vietnam bargirl can be, I can give you one example. A man brought me to America in 1974. He says he loves me and I say I love that man. When I meet him in Saigon, he works in the embassy of America. He can bring me to this country even before he marries me. He says he wants to marry me and maybe I think that this idea scares me a little bit. But I say, what the hell. I love him. Then boom. I’m in America and this man is different from in Vietnam, and I guess he thinks I am different, too. How dumb is a Saigon bargirl is this. I hear him talk to a big crowd of important people in Vietnam — businessman, politician, big people like that. I am there, too, and I wear my best aó dài, red like an apple, and my qu  n, my silk trousers, are white. He speaks in English to these Vietnam people because they are big, so they know English. Also my boyfriend does not speak Vietnam. But at the end of his speech he says something in my language and it is very important to me.

n, my silk trousers, are white. He speaks in English to these Vietnam people because they are big, so they know English. Also my boyfriend does not speak Vietnam. But at the end of his speech he says something in my language and it is very important to me.

You must understand one thing about the Vietnam language. We use tones to make our words. The sound you say is important, but just as important is what your voice does, if it goes up or down or stays the same or it curls around or it comes from your throat, very tight. These all change the meaning of the word, sometimes very much, and if you say one tone and I hear a certain word, there is no reason for me to think that you mean some other tone and some other word. It was not until everything is too late and I am in America that I realize something is wrong in what I am hearing that day. Even after this man is gone and I am in New Orleans, I have to sit down and try all different tones to know what he wanted to say to those people in Saigon.

He wanted to say in my language, “May Vietnam live for ten thousand years.” What he said, very clear, was, “The sunburnt duck is lying down.” Now, if I think this man says that Vietnam should live for ten thousand years, I think he is a certain kind of man. But when he says that a sunburnt duck is lying down — boom, my heart melts. We have many tales in Vietnam, some about ducks. I never hear this tale that he is telling us about, but it sounds like it is very good. I should ask him that night what this tale is, but we make love and we talk about me going to America and I think I understand anyway. The duck is not burned up, destroyed. He is only sunburnt. Vietnam women don’t like the sun. It makes their skin dark, like the peasants. I understand. And the duck is not crushed on the ground. He is just lying down and he can get up when he wants to. I love that man for telling the Vietnam people this true thing. So I come to America and when I come here I do not know I will be in more bars. I come thinking I still love that man and I will be a housewife with a toaster machine and a vacuum cleaner. Then when I think I don’t love him anymore, I try one last time and I ask him in the dark night to tell me about the sunburnt duck, what is that story. He thinks I am one crazy Vietnam girl and he says things that can bum Miss Noi more than the sun.

So boom, I am gone from that man. There is no more South Vietnam and he gives me all the right papers so I can be American and he can look like a good man. This is all happening in Atlanta. Then I hear about New Orleans. I am a Catholic girl and I am a bargirl, and this city sounds for me like I can be both those things. I am twenty-five years old and my titties are small, especially in America, but I am still number-one girl. I can shake it baby, and soon I am a dancer in a bar on Bourbon Street and everybody likes me to stay a Vietnam girl. Maybe some men have nice memories of Vietnam girls.

I have nice memories. In Saigon I work in a bar they call Blossoms. I am one blossom. Around the comer I have a little apartment. You have to walk into the alley and then you go up the stairs three floors and I have a place there where all the shouting and the crying and sometimes the gunfire in the street sounds very far away. I do not mix with the other girls. They do bad things. Take drugs, steal from the men. One girl lives next to me in Saigon and she does bad things. Soon people begin to come in a black car. She goes. She likes that, but I do not talk to her. One day she goes in the black car and does not come back. She leaves everything in her place. Even her Buddha shrine to her parents. Very bad. I live alone in Saigon. I have a double bed with a very nice sheet. Two pillows. A cedar closet with my clothes, which are very nice. Three aó dàis, one apple red, one blue like you see in the eyes of some American man, one black like my hair. I have a glass cabinet with pictures. My father. Some two or three American men who like me very special. My mother. My son.

Читать дальше

n, my silk trousers, are white. He speaks in English to these Vietnam people because they are big, so they know English. Also my boyfriend does not speak Vietnam. But at the end of his speech he says something in my language and it is very important to me.

n, my silk trousers, are white. He speaks in English to these Vietnam people because they are big, so they know English. Also my boyfriend does not speak Vietnam. But at the end of his speech he says something in my language and it is very important to me.