I naturally thought he was talking to me, but when I said, “Yes, that’s right,” he snapped his head around as if he’d forgotten that I was there.

What could I have said to such a reaction? I should have spoken of it to him right away. But I treated it as I would treat Mai waking from a dream and not knowing where she is. I said, “We’re less than twenty miles from Lake Charles, Mr. Chinh.”

He did not reply, but his face softened, as if he was awake now. I said, “Mai can’t wait to see you. And our children are very excited.”

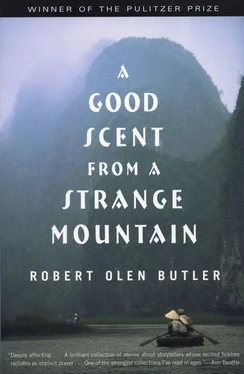

He did not acknowledge this, which I thought was rude for the grandfather who was becoming the elder of our household. Instead, he looked out the window again, and he said, “My favorite car of all was a Hotchkiss. I had a 1934 Hotchkiss. An AM80 tourer. It was a wonderful car. I would drive it from Saigon to Hanoi. A fine car. Just like the car that won the Monte Carlo rally in 1932. I drove many cars to Hanoi over the years. Citroën, Peugeot, Ford, Desoto, Simca. But the Hotchkiss was the best. I would drive to Hanoi at the end of the year and spend ten days and return. It was eighteen hundred kilometers. I drove it in two days. I’d drive in the day and my driver would drive at night. At night it was very nice. We had the top down and the moon was shining and we drove along the beach. Then we’d stop and turn the lights on and rabbits would come out and we’d catch them. Very simple. I can see their eyes shining in the lights. Then we’d make a fire on the beach. The sparks would fly up and we’d sit and eat and listen to the sea. It was very nice, driving. Very nice.”

Mr. Chinh stopped speaking. He kept his face to the wind and I was conscious of the hum of my Acura’s engine and I felt very strange. This man beside me was rushing along the South China Sea. Right now. He had felt something so strong that he could summon it up and place himself within it and the moment would not fade, the eyes of the rabbits still shone and the sparks still climbed into the sky and he was a happy man.

Then we were passing the oil refineries west of the lake and we rose on the I-10 bridge and Lake Charles was before us and I said to Mr. Chinh, “We are almost home now.”

And the old man turned to me and said, “Where is it that we are going?”

“Where?”

“You’re the friend of my nephew?”

“I’m the husband of Mai, your granddaughter,” I said, and I tried to tell myself he was still caught on some beach on the way to Hanoi.

“Granddaughter?” he said.

“Mai. The daughter of your daughter Chim.” I was trying to hold off the feeling in my chest that moved like the old man’s hair was moving in the wind.

Mr. Chinh slowly cocked his head and he narrowed his eyes and he thought for a long moment and said, “Chim lost her husband in the sea.”

“Yes,” I said, and I drew a breath in relief.

But then the old man said, “She had no daughter.”

“What do you mean? Of course she had a daughter.”

“I think she was childless.”

“She had a daughter and a son.” I found that I was shouting. Perhaps I should have pulled off to the side of the road at that moment. I should have pulled off and tried to get through to Mr. Chinh. But it would have been futile, and then I would still have been forced to take him to my wife. I couldn’t very well just walk him into the lake and drive away. As it was, I had five more minutes as I drove to our house, and I spent every second trying carefully to explain who Mai was. But Mr. Chinh could not remember. Worse than that. He was certain I was wrong.

I stopped at the final stop sign before our house and I tried once more. “Mai is the daughter of Nho and Chim. Nho died in the sea, just as you said. Then you were like a father to Mai. . you carried her on your back.”

“My daughter Chim had no children. She lived in Nha Trang.”

“Not in Nha Trang. She never lived in Nha Trang.”

Mr. Chinh shook his head no, refuting me with the gentleness of absolute conviction. “She lived on the beach of Nha Trang, a very beautiful beach. And she had no children. She was just a little girl herself. How could she have children?”

I felt weak now. I could barely speak the words, but I said, “She had a daughter. My wife. You love her.”

The old man finally just turned his face away from me. He sat with his head in the window as if he was patiently waiting for the wind to start up again.

I felt very bad for my wife. But it wasn’t that simple. I’ve become a blunt man. Not like a Vietnamese at all. It’s the way I do business. So I will say this bluntly. I felt bad for Mai, but I was even more concerned for myself. The old man frightened me. And it wasn’t in the way you might think, saying to myself, Oh, that could be me over there sitting with my head out the window and forgetting who my closest relatives are. It was different from that, I knew.

I drove the last two blocks to our house on the corner. The long house with the steep roof and the massively gnarled live oak in the front yard. My family heard my car as I turned onto the side street and then into our driveway. They came to the side door and poured out and I got out of the car quickly, intercepting the children. I told my oldest son to take the others into the house and wait, to give their mother some time alone with her grandfather, who she hadn’t seen in so many years. I have good children, obedient children, and they disappeared again even as I heard my wife opening the car door for Mr. Chinh.

I turned and looked and the old man was standing beside the car. My wife embraced him and his head was perched on her shoulder and there was nothing on his face at all, no feeling except perhaps the faintest wrinkling of puzzlement. Perhaps I should have stayed at my wife’s side as the old man went on to explain to her that she didn’t exist. But I could not. I wished to walk briskly away, far from this house, far from the old man and his granddaughter. I wished to walk as fast as I could, to run. But at least I fought that desire. I simply turned away and moved off, along the side of the house to the front yard.

I stopped near the live oak and looked about, trying to see things. Trying to see this tree, for instance. This tree as black as a charcoal cricket and with great lower limbs, as massive themselves as the main trunks of most other trees, shooting straight out and then sagging and rooting again in the ground. A monstrous tree. I leaned against it and as I looked away, the tree faded within me. It was gone and I envied the old man, I knew. I envied him driving his Hotchkiss along the beach half a century ago. Envied him his sparks flying into the air. But my very envy frightened me. Look at the man, I thought. He remembered his car, but he can’t remember his granddaughter.

And I demanded of myself: Could I? Even as I stood there? Could I remember this woman who I loved? I’d seen her just moments ago. I’d lived with her for more than twenty years. And certainly if she was standing there beside me, if she spoke, she would have been intensely familiar. But separated from her, I could not picture her clearly. I could construct her face accurately in my mind. But the image did not bum there, did not rush upon me and fill me up with the feelings that I genuinely held for her. I could not put my face into the wind and see her eyes as clearly as Mr. Chinh saw the eyes of the rabbits in his headlights.

Not the eyes of my wife and not my country either. I’d lost a whole country and I didn’t give it a thought. V  ng Tàu was a beautiful city, and if I put my face into the wind, I could see nothing of it clearly, not its shaded streets or its white-sand beaches, not the South China Sea lying there beside it. I can speak these words and perhaps you can see these things clearly because you are using your imagination. But I cannot imagine these things because I lived them, and to remember them with the vividness I know they should have is impossible. They are lost to me.

ng Tàu was a beautiful city, and if I put my face into the wind, I could see nothing of it clearly, not its shaded streets or its white-sand beaches, not the South China Sea lying there beside it. I can speak these words and perhaps you can see these things clearly because you are using your imagination. But I cannot imagine these things because I lived them, and to remember them with the vividness I know they should have is impossible. They are lost to me.

Читать дальше

ng Tàu was a beautiful city, and if I put my face into the wind, I could see nothing of it clearly, not its shaded streets or its white-sand beaches, not the South China Sea lying there beside it. I can speak these words and perhaps you can see these things clearly because you are using your imagination. But I cannot imagine these things because I lived them, and to remember them with the vividness I know they should have is impossible. They are lost to me.

ng Tàu was a beautiful city, and if I put my face into the wind, I could see nothing of it clearly, not its shaded streets or its white-sand beaches, not the South China Sea lying there beside it. I can speak these words and perhaps you can see these things clearly because you are using your imagination. But I cannot imagine these things because I lived them, and to remember them with the vividness I know they should have is impossible. They are lost to me.