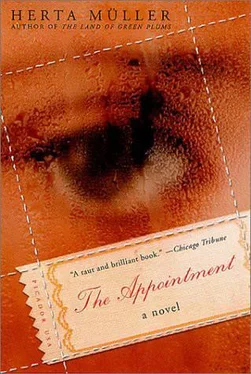

Herta Müller

The Appointment

I’ve been summoned . Thursday, at ten sharp.

Lately I’m being summoned more and more often: ten sharp on Tuesday, ten sharp on Saturday, on Wednesday, Monday. As if years were a week, I’m amazed that winter comes so close on the heels of late summer.

On my way to the tram stop, I again pass the shrubs with the white berries dangling through the fences. Like buttons made of mother-of-pearl and sewn from underneath, or stitched right down into the earth, or else like bread pellets. They remind me of a flock of little white-tufted birds turning away their beaks, but they’re really far too small for birds. It’s enough to make you giddy. I’d rather think of snow sprinkled on the grass, but that leaves you feeling lost, and the thought of chalk makes you sleepy.

The tram doesn’t run on a fixed schedule.

It does seem to rustle, at least to my ear, unless those are the stiff leaves of the poplars I’m hearing. Here it is, already pulling up to the stop: today it seems in a hurry to take me away. I’ve decided to let the old man in the straw hat get on ahead of me. He was already waiting when I arrived — who knows how long he’d been there. You couldn’t exactly call him frail, but he’s hunchbacked and weary, and as skinny as his own shadow. His backside is so slight it doesn’t even fill the seat of his pants, he has no hips, and the only bulges in his trousers are the bags around his knees. But if he’s going to go and spit, right now, just as the door is folding open, I’ll get on before he does, regardless. The car is practically empty; he gives the vacant seats a quick scan and decides to stand. It’s amazing how old people like him don’t get tired, that they don’t save their standing for places where they can’t sit. Now and then you hear old people say: There’ll be plenty of time for lying down once I’m in my coffin. But death is the last thing on their minds, and they’re quite right. Death never has followed any particular pattern. Young people die too. I always sit if I have a choice. Riding in a seat is like walking while you’re sitting down. The old man is looking me over; I can sense it right away inside the empty car. I’m not in the mood to talk, though, or else I’d ask him what he’s gaping at. He couldn’t care less that his staring annoys me. Meanwhile half the city is going by outside the window, trees alternating with buildings. They say old people like him can sense things better than young people. Old people might even sense that today I’m carrying a small towel, a toothbrush, and some toothpaste in my handbag. And no handkerchief, since I’m determined not to cry. Paul didn’t realize how terrified I was that today Albu might take me down to the cell below his office. I didn’t bring it up. If that happens, he’ll find out soon enough. The tram is moving slowly. The band on the old man’s straw hat is stained, probably with sweat, or else the rain. As always, Albu will slobber a kiss on my hand by way of greeting.

Major Albu lifts my hand by the fingertips, squeezing my nails so hard I could scream. He presses one wet lip to my fingers, so he can keep the other free to speak. He always kisses my hand the exact same way, but what he says is always different:

Well well, your eyes look awfully red today.

I think you’ve got a mustache coming. A little young for that, aren’t you.

My, but your little hand is cold as ice today — hope there’s nothing wrong with your circulation.

Uh-oh, your gums are receding. You’re beginning to look like your own grandmother.

My grandmother didn’t live to grow old, I say. She never had time to lose her teeth. Albu knows all about my grandmother’s teeth, which is why he’s bringing them up.

As a woman, I know how I look on any given day. I also know that a kiss on the hand shouldn’t hurt, that it shouldn’t feel wet, that it should be delivered to the back of the hand. The art of hand kissing is something men know even better than women — and Albu is hardly an exception. His entire head reeks of Avril, a French eau de toilette that my father-in-law, the Perfumed Commissar, used to wear too. Nobody else I know would buy it. A bottle on the black market costs more than a suit in a store. Maybe it’s called Septembre, I’m not sure, but there’s no mistaking that acrid, smoky smell of burning leaves.

Once I’m sitting at the small table, Albu notices me rubbing my fingers on my skirt, not only to get the feeling back into them but also to wipe the saliva off. He fiddles with his signet ring and smirks. Let him: it’s easy enough to wipe off somebody’s spit; it isn’t poisonous, and it dries up all by itself. It’s something everybody has. Some people spit on the pavement, then rub it in with their shoe since it’s not polite to spit, not even on the pavement. Certainly Albu isn’t one to spit on the pavement — not in town, anyway, where no one knows who he is and where he acts the refined gentleman. My nails hurt, but he’s never squeezed them so hard my fingers turned blue. Eventually they’ll thaw out, the way they do when it’s freezing cold and you come into the warm. The worst thing is this feeling that my brain is slipping down into my face. It’s humiliating, there’s no other word for it, when your whole body feels like it’s barefoot. But what if there aren’t any words at all, what if even the best word isn’t enough.

I’ve been listening to the alarm clock since three in the morning ticking ten sharp, ten sharp, ten sharp. Whenever Paul is asleep, he kicks his leg from one side of the bed to the other and then recoils so fast he startles himself, although he doesn’t wake up. It’s become a habit with him. No more sleep for me. I lie there awake, and I know I need to close my eyes if I’m going back to sleep, but I don’t close them. I’ve frequently forgotten how to sleep, and have had to relearn each time. It’s either extremely easy or utterly impossible. In the early hours just before dawn, every creature on earth is asleep: even dogs and cats only use half the night for prowling around the dumpsters. If you’re sure you can’t sleep anyway, it’s easier to think of something bright inside the darkness than to simply shut your eyes in vain. Snow, whitewashed tree trunks, white-walled rooms, vast expanses of sand — that’s what I’ve thought of to pass the time, more often than I would have liked, until it grew light. This morning I could have thought about sunflowers, and I did, but they weren’t enough to dislodge the summons. And with the alarm clock ticking ten sharp, ten sharp, ten sharp, my thoughts raced to Major Albu even before they shifted to me and Paul. Today I was already awake when Paul started thrashing in his sleep. By the time the window started turning gray, I had already seen Albu’s mouth looming on the ceiling, gigantic, the pink tip of his tongue tucked behind his lower teeth, and I had heard his sneering voice:

Don’t tell me you’re losing your nerve already — we’re just warming up.

Paul’s kicking wakes me only when I haven’t been summoned for two or three weeks. Then I feel happy, since it means I’ve learned how to sleep again.

Whenever I’ve relearned how to sleep, and I ask Paul in the morning what he was dreaming, he can’t remember anything. I show him how he tosses about and splays his toes, and then how he jerks his legs back and crooks his toes. Moving a chair from the table to the middle of the kitchen, I sit down, stick my legs in the air, and demonstrate the whole procedure. It makes Paul laugh, and I say:

You’re laughing at yourself.

Who knows, maybe I dreamed I was taking you for a ride on my motorcycle.

Читать дальше