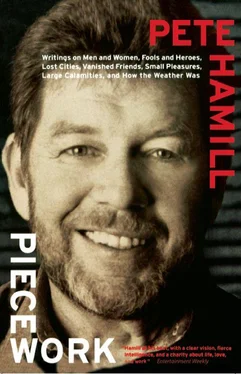

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Hernandez, by all accounts, loves his children; he dotes on them when he is with them, even took a few days out of spring training to take them to Disney World. Marriages end; responsibility does not. Hernandez says that he would like to marry again someday and raise a family, but not until he’s finished with baseball. One sign of maturity is the realization that you can’t have everything.

He also won’t discuss cocaine anymore. At one point, he told writer Joe Klein what it was like around the major leagues in the late ’70s. “All of a sudden, it was everywhere. In the past, you might be in a bar and someone would say, ‘Hey, Keith, wanna smoke a joint?’ Now it was ‘Wanna do a line?’ People I’d never met before were offering; people I didn’t know. Everywhere you went. It was like a wave: it came, and then people began to realize that cocaine could really hurt you, and they stopped.”

Nobody has ever disputed Hernandez’s claim that his cocaine use was strictly recreational; he never had to go into treatment (as teammate Lonnie Smith did); his stats remained consistent. But when Hernandez was traded to the Mets in June 1983 for Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey, the whispering was all over baseball. Cards manager Whitey Herzog would not have traded Hernandez for such mediocre players if the first baseman didn’t have some monstrous drug problem. It didn’t matter that Hernandez almost immediately transformed the Mets into a contender, giving them a professional core, setting an example for younger players, inspiring some of the older men. The whispering went on.

Then, deep into the 1985 season, Hernandez joined the list of professional ballplayers who testified in the Curtis Strong case in Pittsburgh, and the whole thing blew open. In his testimony, Hernandez described cocaine as a demon that got into him, but that was now gone; he had stopped well before the trade to the Mets. He wasn’t the only player named in the Strong case, but he seemed to get most of the ink. When he rejoined the team the next day in Los Angeles, he did the only thing he knew how to do: he went five for five.

When the Mets finally came home to Shea Stadium, Hernandez was given a prolonged standing ovation during his first at-bat. It was as if the fans were telling him that all doubt was now removed: he was a New Yorker forever. Flawed. Imperfect. Capable of folly. But a man who had risen above his own mistakes to keep on doing what he does best. That standing ovation outraged some of the older writers and fans but it moved Hernandez almost to tears. He had to step out of the box to compose himself. Then he singled to left.

Last spring, as Hernandez was getting ready for the new season, baseball commissioner Peter Ueberroth made his decision about punishing the players who had testified in the Strong case. Hernandez was to pay a fine of 10 per cent of his salary (roughly $180,000, to be donated to charity), submit to periodic drug testing, and do 100 hours of community service in each of the next two years. Most of the affected players immediately agreed; Hernandez did not. He objected strongly to being placed in Group 1, those players who “in some fashion facilitated the distribution of drugs in baseball.” In the new afterword to his book If at First… , Hernandez insists: “I never sold drugs or dealt in drugs and didn’t want that incorrect label for the rest of my life.”

There were some obvious constitutional questions. (Hernandez and the other players were given grants of immunity, testified openly, and were punished anyway — by the baseball commissioner — even though they had the absolute right to plead the Fifth Amendment in the first place.) There was also something inherently unfair about punishing a man who came clean. Hernandez threatened to file a grievance, conferred with friends, lawyers, his brother. After a week of the resulting media shitstorm, Hernandez reluctantly agreed to comply, still saying firmly, “The only person I hurt was myself.”

Last year, he took a certain amount of abuse. A group of Chicago fans showed up with dollar bills shoved up their noses. Many Cardinal fans, stirred up by the local press, were unforgiving. And I remember being at one game at Shea Stadium, where a leather-lunged guy behind me kept yelling at Hernandez, “Hit it down da white line, Keith. Hit it down da white line.” Still, Hernandez refused to grovel, plead for forgiveness, appear on the Jimmy Swaggart show, or kiss anyone’s ass. He just played baseball. The Mets won the division, the playoffs, and the World Series, and they couldn’t have done it without him. When The New York Times did a roundup piece a few weeks ago about how the players in the Pittsburgh case had done their community service, Hernandez was the only ballplayer to refuse an interview. His attitude is clear: I did it, it’s over, let’s move on. He plays as hard as he can (slowed these days by bad ankles that get worse on Astroturf) and must know that the Drug Thing might prevent him from ever managing in the major leagues — and could even keep him out of the Hall of Fame.

“I like playing ball,” he says. “That’s where I’m almost always happy.”

III.

Now it’s the spring and everything lies before him. The sports pages are full of questions: what’s the matter with Gooden and why isn’t Dykstra hitting and will the loss of Ray Knight change everything and why does McReynolds look so out to lunch. Nobody writes much about Hernandez; his career and his style don’t provoke many questions. He will tell you that he thinks Don Mattingly is “the best player in the game today,” but admits that he seldom watches American League games and isn’t even interested in playing American League teams in spring. The next day, for example, the Mets are scheduled to play the Blue Jays in nearby Dunedin. “I’d rather not even go,” says Hernandez. “It’s a shit park and we’re never gonna play these guys, so why?”

In the clubhouse, nothing even vaguely resembles a headline; Hernandez does talk in an irritated way about Strawberry, as if the sight of such natural gifts being inadequately used causes him a kind of aesthetic anger. “Last year, he finally learned how to separate his offense from his defense and that’s a major improvement,” Hernandez says. “Before, if he wasn’t hitting, he’d let it affect his fielding. Not last year.”

His locker is at the opposite end of the clubhouse from that of Gary Carter, who is the other leader of the club. I’m told that some players are Carter men, some Hernandez men. There could not be a greater difference in style. Carter is Mister Good Guy America, right out of the wholesome Steve Garvey mold. You can imagine him as a Los Angeles Dodger — but not a Brooklyn Dodger. He smiles most of the time and even his teeth seem to have muscles; he radiates fair-haired good health; if a demon has ever entered him, he shows no signs of the visit.

You can see Carter on a horse, or kicking up dust with a Bronco on some western backcountry road or strolling toward you on the beach at Malibu. Hernandez is dark, reflective, analytical, urban. Through the winter, you see him around the saloons of the city, sometimes with friends like Phil McConkey of the Giants, other times with beautiful women. His clothes are carefully cut. He reads books, loves history, buys art for his apartment on the East Side. Carter is the king of the triumphant high-fives; Hernandez seems embarrassed by them. In a crisis, Carter might get down on a knee and have a prayer meeting; Hernandez advocates a good drunk. Between innings, Carter gives out with the rah-rah on the bench; Hernandez is in the runway smoking a cigarette.

They are friendly, of course, in the casual way that men on the same team are friendly. But it’s hard to imagine them wandering together through the night. Hernandez speaks about his personal loneliness and fear; Carter smiles through defeat and promises to be better tomorrow. Both are winners. In some odd way, they were forever joined, forever separated, during the Greatest Game Ever Played (well, one of them): the 6th playoff game against Houston. In the 14th inning, Billy Hatcher hit a home run off Jesse Orosco to tie the game. There was a hurried conference on the mound. Hernandez later said he told Carter, “If you call another fastball, I’ll fight you right here.” Carter insists that the words were never uttered, telling Mark Ribowsky of Inside Sports: “Keith never said that, he just told the press that he did out of the tension of the game. I call the pitches and / decided not to throw anything after that but Jesse’s slider, his best pitch. Let’s get that straight once and for all.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.