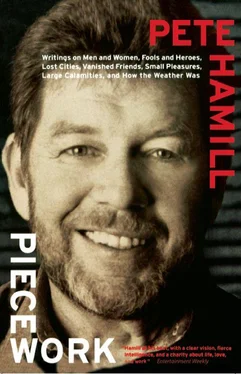

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He talked about Sugar Ray Robinson and Lester Young, Akira Kurosawa and Brigitte Bardot. He asked me about Pratt, where he had taught a few years earlier (as had Isamu Noguchi, George McNeil, Adolph Gottlieb, and Richard Lindner, among other stars of the New York art world). “You can help teach people how to draw,” he said, “but you can’t teach them to be painters. All you can do is let them know they better love it or get the hell out.”

At some point we started talking about cartoonists. His face brightened as he sipped his beer. “I wanted to be a cartoonist when I started out. I wanted that more than anything.” He loved the cartoons of Willard Mullin in the World-Telegram. (“I don’t know how he does it, day after day, on that level. The guy’s a genius.”) He was the first man to tell me he was a fan of the amazing Cliff Sterrett, whose surrealistic comic strip, “Polly and her Pals,” was usually overlooked by the solemn analysts of popular culture. And of course he paid homage to George Herriman, whose “Krazy Kat” was the highbrows’ favorite comic strip. “But you know,” he said, “I even like ‘Orphan Annie.’ The politics are neanderthal. But the man knows how to use blacks.”

I was astonished. This was years before pop art was proclaimed by critics as the successor to abstract expressionism. No painter’s vision seemed more distant from cartooning than the great bold abstractions of Franz Kline. But as he talked that night, I realized that it was comics that had made him want to be an artist. Born in 1910, he grew up in the ’20s with John Held Jr. as his hero. Held’s drawings in the old Life and Judge and Vanity Fair made him the most famous cartoonist of his time. In their way, Held’s short-skirted flappers and bell-bottomed college boys expressed the hedonism and silliness of the Roaring Twenties as powerfully as the stories of Scott Fitzgerald. But Kline saw form as well as content; he liked the way Held designed a page, placing a number of figures in the space but using blacks to establish a pattern that became the true structure of the drawing.

Kline also talked with affection of certain illustrators and figurative painters. He admired Jack Levine and praised John Sloan and Reginald Marsh, who in different ways had embraced the energy and tension of the city the way the New York School did with pure paint. (Kline once said to Irving Sandier, “Hell, half the world wants to be like Thoreau at Walden, worrying about the noise of traffic on the way to Boston; the other half use up their lives being part of that noise. I like the second half.”) As we talked, he was amused, perhaps even delighted, that I knew the work of the British pen-and-ink illustrators — men like John Leech, Donald Keene, and above all Phil May, who tried to turn the city into art.

“Phil May got me to go to England,” Kline said. “I wanted to draw like he did, that big open confident way.” Franz Kline in England? Yes: before the war. After two years at Boston University’s School of Fine and Applied Art, he moved to London in 1935 and enrolled in art school. He was apparently not much touched by the political fevers of the day: the Spanish Civil War, the threat of fascism, the romance of communism. Instead, he absorbed the look of architecture, trains, bridges, ships, theaters, music halls. He spent hundreds of hours drawing the figure and mastering the principles of composition. He walked the streets that once teemed with Phil May’s ragamuffins. He looked hard at the drawings of the Frenchmen: Daumier, Steinlen, and Forain. In London, the dream of a career as a cartoonist gave way to the desire to be an illustrator.

London also had a certain logic for the young man who became Franz Kline. With the grand exception of Turner, it had produced great draftsmen rather than colorists (Hogarth, Rowlandson, Tenniel, du Maurier, Gillray, Phiz). For Franz, London must have been a gloriously dark indoor city of black and white. I often wonder what his art would have been like if he’d gone instead to Venice or Mexico.

“I had a good time there,” he said of London. “I was never so hungry in my life. But I really did learn to draw.”

When I mentioned that I’d spent a year in art school in Mexico, his eyes brightened and he laughed. “When I came back from London, everybody around was trying to be Orozco or Siqueiros, except the guys who wanted to be Mondrian.” He and his wife (whom he’d met in England) moved to Manhattan in 1938, with Franz now determined to be a fine artist. He missed being part of the great brawling fraternity of New York artists who worked for the WPA, but he slowly got to know most of them in the bohemian bars of Greenwich Village. “Some of them liked the Mexicans because of the politics,” Kline said. “Some, like Jackson, for the size of the work.” He shrugged. “I didn’t care for all of them, but I liked the attempt, you know? They could all draw. They had power. They were trying to do something big.”

Listening to Kline talk at the height of his fame, in a voice whose confident baritone seemed to match the blacks of his paintings, I felt something else brewing under the polished, generous surface. I was too young to identify it, but I think now that he probably knew his own huge achievement was only provisional. He’d done Something Big too. But now there were dozens of kids at Pratt belting out “Klines” (or Pollocks or Rothkos or de Koonings) and talking in the opaque codes of the new art theorists. Rebellion was undergoing its familiar transformation into orthodoxy.

The young hadn’t struggled through the rigorous art schools of the ’30s, hadn’t been challenged by the Depression or the war, hadn’t been forced to support themselves by doing murals for bars (as Kline had done at Minetta’s and the Bleecker Street Tavern). Not one of them would have done a mural for an American Legion Post, as Kline had done in 1946 back home in Lehighton, Pennsylvania, four years before he broke through into the style that made him famous.

For Kline’s generation, the work of the artist could be defined not simply by what he did, but what he refused to do. They had struggled to make an art that was uniquely American: not pseudo-European, neo-Mexican, or some additional knockoff of Picasso. They wanted to be as American as the comic strip or jazz. The best of them certainly didn’t want to be rich or famous; if anything, they shared a romantic view of the clarifying power of poverty. They wouldn’t pander to an audience, or shape their work to please collectors or museum directors or even critics (although Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg did have an enormous influence on the artists who came right after the first generation). They hated glibness and facility; they thought the American artist had a special responsibility to be original (the worst epithet was “derivative”). They expected the artist to live or die in every brushstroke (they’d have hung the likes of Mark Kostabi from a lamppost on Eighth Street), to paint as if he or she might die before morning.

It was a heroic enterprise. Macho: yes. Self-destructive: sometimes. Safe, timid, conniving, calculated: never. And they’d accomplished much of what they’d set out to do, shifting the center of Western art from Paris to New York. But by 1958, other words were being spoken: exhaustion, repetition, mannerism. And Franz must have heard them too.

“It’s closing time, isn’t it?” he said one night, gazing around at the almost empty Cedar. And then he led a few of us up to Fourteenth Street for a nightcap at his studio. I’d never been in a real painter’s studio before. That dark loft was clearly a place of work. I could see rolls of canvas, buckets of paint, large house-painters’ brushes, cans of turpentine, baking pans caked with paint. The floor looked like a Pollock. There were small painted drawings scattered around, some of them on the floor, proof that Franz knew what he was going to paint when he approached the canvas. The public image of the action painters was, of course, a crude cartoon. In their work, they could express anger, serenity, anxiety, a contempt for the slick and the sentimental. But for men like Franz Kline, painting was never mere performance or raw therapy. They were making art.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.