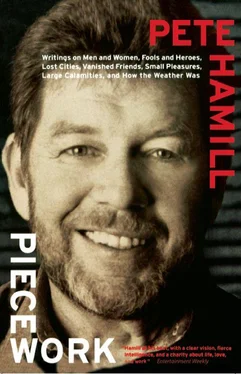

Pete Hamill - Piecework

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Pete Hamill - Piecework» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, ISBN: 2009, Издательство: Little, Brown and Company, Жанр: Современная проза, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Piecework

- Автор:

- Издательство:Little, Brown and Company

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:9780316082952

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Piecework: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Piecework»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

offers sharp commentary on diverse subjects, such as American immigration policy toward Mexico, Mike Tyson, television, crack, Northern Ireland and Octavio Paz.

Piecework — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Piecework», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Also surviving from the pre-Conquest days is the monument to Tepozteco on top of the mountain of the same name, rising a thousand abrupt feet above the village. This was built by the Aztecs on a familiar pyramid base to honor the god of drunkenness, the inventor of pulque, a white, slightly sweet brew made from the maguey plant. The old tales insist that when the Spaniards arrived, they hurled the idol off its pedestal into the valley below. But to the delight of the inhabitants, it did not break. The conquerors were forced to attack it with hammers and saws, breaking it into chips and dust. Today, the base of the old pyramid remains on top of the mountain, badly eroded, but with some of the ancient decorations still visible; you can reach it on a hiking trail. The view of the valley from the peak is glorious. But Tepozteco is more than a view. In September of each year, a fiesta honors the old idol, and much pulque is drunk by nominal Catholics, and many dances danced. Here, human beings hold on to sensible gods.

In the slow afternoons in Tepoztlán, moving through the amber torpor of the sun, you can still see those small powerful women, built like tree trunks, pounding fresh tortillas on three-legged metates as their ancestors did for centuries. You can buy chickens killed that morning. You can see boys negotiating the cobblestones of Avenida de la Revolución on burros, comic books jutting from their back pockets. There are a few good restaurants, but most people here eat at home, as they always did. They seem entirely indifferent to the groups of city people who own second homes here as refuges from the horrors of modern Mexico City: writers and painters, businessmen and intellectuals, and a few American expatriates. This is a proud town in a state of proud people. They don’t kowtow to strangers but they almost never descend to rudeness either. At the same time, you witness none of the fawning theatrics of those who live in tourist towns. And you see no beggars.

What you do sense, if you read the history and allow the town’s layered past to seep into you slowly, is the eventual triumph of Zapata. The agrarian reform for which he lived and died came slowly. In the early years, the campesinos were given the worst land: on untillable mountain slopes, in places devoid of water or topsoil. The new politicians, the thick-fingered hustlers of the revolution, grabbed the best land for themselves.

Irony was without limit. In Anenecuilco, where Zapata was born, the worst abuser of the campesinos in the 1940s was a man named Nicolas Zapata. He was 13 when his father, Emiliano, was killed. Everywhere, human beings have a gift for outrage. But during the presidency of Lázaro Cardenas (1934-1940), the worst abuses were ended. Schools and hospitals were opened, transportation made easier, farmers helped with credit and supplies. Eventually, Nicolas Zapata was hustled out of Morelos.

The people of Zapata country soon had to face a harder task than the fighting of a revolution. As Mexico’s population soared in the 1940s, a new generation soon learned the obvious: There simply wasn’t enough arable land to be divided up, generation after generation; even the holy Mexican tierra was finite. Many young people from Morelos began to emigrate, to Cuernavaca, to Mexico City, to the United States. Some never came back. Obviously, agrarian reform wasn’t the answer to all of the problems of Morelos or Mexico; in this world, nothing is the answer.

And yet, for all of the disappointments, there is something about the people of Morelos that is healthy and enduring: They bow their heads to no man. That is surely the most valuable inheritance passed down by the generation of Emiliano Zapata. That is Zapata’s triumph. He wanted humble people to be proud. Not vain. Not haughty. Proud. And you sense that pride here in the way ordinary citizens move, in the confident (if reserved) way in which they deal with strangers. You see it in the way they take care of their children and their homes. You see it in the poorest barrios, where flowers are planted in tin cans on doorsteps and windowsills.

The pride is not merely in self, but in place. The anthropologist Oscar Lewis believed that the name Tepoztlán means “place of the broken rocks,” after the spectacular peaks and buttes that rise above the town. If so, the name is no longer completely accurate. The name doesn’t truly describe the abundant beauty of bougainvillea and avocado trees, the citrus green in the sun, the mango and papaya trees, the fields of coffee and bananas appearing around a sudden bend. Nor does it portray the handsome homes of the city people who have moved here in the past few decades, adding the bright shimmer of swimming pools to the town, behind walls of volcanic rock. Nor does the name explain why so many of those who went away have begun to return, as dismayed as Zapata by what they encountered in the cement streets of big cities, explaining that at least here they had “petates y parientes “ — a place to sleep, and parents, too.

In short, the name of Tepoztlán doesn’t explain the beauty of the place, or its mood, or its ghosts. Sometimes they all appear after the sun has vanished. You walk here at night with no sense of the menace that stains the night in almost all the cities of el Norte. On the dirt roads of the lower town, faceless strangers pass in the dark and murmur hello. A few drunks sing the old canciones. Somewhere, but never seen, dogs are always barking, and the odor of jasmine thickens the air. On such a night not long ago, as I sat behind the house, gazing up at the black silhouette of the mountains, the wind shifted subtly and a cloud acquired the gleaming texture of mother-of-pearl: still, beautiful, perfect. The moon was hidden. A lone dog howled. And I swear that up on the ridge, high above this dark valley in Morelos, I saw a white horse.

TRAVEL HOLIDAY,

October 1990

EL NOBEL

Out on Fifth Avenue, the crowd is unusual for an urban evening in the last decade of the American century. Nobody fires a gun. Nobody plays a giant radio. Nobody speaks at full moronic bellow or offers dope for sale or screams in utter loneliness for help. But the people here are as excited as any group in thrall to the usual New York distractions of noise or violence. They are gathered outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art to hear a talk by Octavio Paz.

Paz is seventy-six, Mexican, a poet, an essayist, a critic, and an editor. Naturally, most Americans have never heard of him. Not even on this evening, a few days after Paz has been awarded the 1990 Nobel Prize for literature.

“What’s the line for?” a young American asks me, outside the museum. “Who they waitin’ to see?”

“Octavio Paz.”

“Who?”

In Mexico, of course, Paz is a gigantic, luminous star. So it was no surprise that the Mexican newspapers carried the story of the Nobel award in type sizes usually reserved for declarations of war or victories in the World Cup. Paz is not the first Latin American to win, but he is the first Mexican. And though he has directed the energies of a long lifetime against dumb nationalism, Paz did not defuse the surge of Mexican national pride by turning down the award or the $700,000 that goes with it. And why should he have? In a time of slick frauds, Octavio Paz is an authentic world-class writer; nobody can say of him that he did not deserve the Nobel Prize. And nobody knows this better than Paz.

A great writer belongs to people everywhere. I remember seeing Paz on Avenida Juárez in Mexico City in the early 1970s, after he’d returned from a few years of exile. He came out of a bookstore looking exactly the way a poet should look: handsome, distracted, his hair in need of tending, the collar of his shirt curling, a small bundle of books in his hand. He was alone. A young man recognized him, perhaps for the same reason I did: an appearance on television two nights earlier.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Piecework»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Piecework» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Piecework» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.