That’s the place Janice wanted me to go to! Yes. Is she okay? Did she get hurt? Where the hell is she? A terrorist attack? On a disco? Makes no sense.

Then the anchorman is on. Making a clumsy segue. Meanwhile, the investigation of the murders in Greenwich Village of… She clicks off the sound and looks away, sips the beer, gets up, walks to a window to watch the driving snow. She counts to fifty and turns to the set. The anchorman again. Then a head shot of Myles! A kind of mug shot, without numbers underneath. Flicks on sound. Police in Putnam County believe they have found the body of a Wall Street man who failed to show up at a federal grand jury today. The man: Myles Compton. The body was found by two snowboarders. The man was shot twice in the head. Federal investigators had no comment but—

She turns off the set.

Sits there in silence.

Thinking: God, I’m too old for this.

Refusing to shed even one more tear.

9:16 p.m. Sam Briscoe. Our Lady of Guadalupe, 14th Street.

There is no Mass under way, but the lights are shining. He has slipped into a pew in the rear. The familiar image of the Lady of Guadalupe is high on the altar, her dark Indian skin a sign of triumphant consolation, with some kind of painted blue stream spreading beneath her. He has seen her in many places. In Mexico, above all. In the old Mexico City cathedral where pilgrims come each December to celebrate her goodness, hundreds doing the last few miles on their knees, to leave painted tin retablos asking for her intercession. The lights in this church do not burn now at full strength, except on the Virgin herself. Green-painted pillars rise to the high dark ceiling. But Briscoe can see people scattered through the pews. Everyone is alone. No couples. No mothers and children. Few men at all. Up near the front on the right, there’s someone in a wheelchair. Out in the aisle. To the right and left of the altar, candles burn in rows, and one older woman goes up and drops a coin in a slot and lights a fresh one.

Briscoe is certain he can smell the burning wax. Even here, far from the altar. He considers lighting some candles of his own. For Cynthia and Mary Lou. Of course. But for Ali Watson too. For Sandra. For her asshole boyfriend. For all the others, in those solitary rooms above the streets. For women scrubbing offices until the midnight hour. For baffled junkies in doorways. For my long-dead wife. For everyone at the paper. For the Fonseca kid, who thought he’d wear the same press card for years, and now… For all of them. People of the night.

He hears the elegance of Gregorian chant seeping into the dark places of the church, imposing grace and order out of the past. A CD, for sure. Briscoe thinks: Maybe we could bury Cynthia out of this place.

Maybe.

She would like that.

Briscoe tries again to pray. Once more, the words won’t come. And he can’t convince himself to walk up to the rack of guttering candles. He stands and hurries back to the doors. The cold hits him hard. He shudders, moves his hands like a prizefighter, snorts. Then goes down a shoveled path on the steps. He starts walking east, into the snow-drowned city. The wind is at his back.

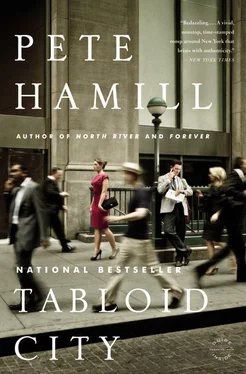

Pete Hamillis a novelist, journalist, editor, and screenwriter. He is the author of twenty previous books, including the bestselling novels Forever and Snow in August and the bestselling memoir A Drinking Life. He lives in New York City.

www.petehamill.com

A conversation with Pete Hamill

Pete Hamill’s apartment is a New York bibliophile’s dream. It has high ceilings, wall-to-wall books (loosely organized by global region), and priceless natural light. When I arrive to talk with him about his latest novel, Tabloid City, he apologizes for not having any coffee to offer, explaining that his wife, the novelist Fukiko Aoki, is currently in Japan. (She is apparently the coffee lover of the two.) I tell him that “it’s cool” and also that “water will be fine.” And it is.

Hamill’s book takes place in a manic twenty-four-hour span in present-day New York City, and it’s a singularly bad day for newspaper editor Sam Briscoe. His beloved newspaper is being turned into a website, the love of his life has met with horrible tragedy, and the city is changing faster than he can adapt to, even assuming he wants to. Add to that the threat of an imminent terrorist attack and a vindictive blogger, and you have the makings of a tabloid experience in novel form, something that Hamill, the lifelong newspaperman, knows a little something about.

On your website, you describe yourself as a generalist and not a specialist. This book, Tabloid City, seems to encapsulate many of your diverse interests, including newspapers, art, comics, and New York. You’ve reported on many of these things throughout your career, so what’s the benefit of putting them into fiction for you?

Well, obviously one great advantage of fiction over journalism is the great difference between them. Fiction is an act of the imagination. I can go into the interior lives of people, which I can’t do in journalism. I can’t do that. People can tell me what their internal lives might be, or suggest them, but people lie, too. [Laughs.] And so as a journalist, you’re always skeptical about what people tell you. In this particular novel, I did use the tools of journalism. It’s a cliché about suspending the reader’s disbelief by getting the reportable world down as accurately as possible. And then within that, getting the imaginative sense of these characters, who can be anything — they can be composites, they can be lives that are suggested by people you knew long ago but who are dead and gone — you can take parts of their character and use them the way you want to. And that’s why I think so many journalists do eventually write fiction. Stephen Crane, Charles Dickens, Hemingway, and a whole slew of other much greater writers than I am. But they learned something from the journalism about its limitations. And then you try to use fiction to make some of that work in a believable way. So that’s what I try to do.

So Sam Briscoe, now that he’s retiring from newspapers, is going to go write a novel?

[Laughs.] I think he’s going to Paris with the rest of the people. Get a little night rewrite at the Paris Herald Tribune. There’s only about four people left on the staff. No, I think because it’s twenty-four hours, and the two most important things in his life have ended — this woman that he has been together with for more than twenty years, and the newspaper. And at seventy-one, he’s not going to go apply for jobs anywhere. He just won’t do that. I think he’ll go out and read books…

Is it safe to say that there is a fair amount of Pete Hamill in Sam Briscoe?

Sure. But there is also a fair amount of me in the Mexican immigrant from Sunset Park. The old Madame Bovary “C’est moi” effect that all fiction writers are conscious of. But some of the biography is different, obviously. Sam grew up in Manhattan, I grew up in Brooklyn. His father is Jewish, my father is Belfast Catholic. He’s younger than I am. But also, part of Sam’s character comes from people I knew. Most importantly, Paul Sann, who was the editor of the [New York] Post when I started, in 1960. I remember so clearly one day. Paul’s wife had died just hours before. She was someone he loved deeply. You could tell when you saw them together. It was the small things. Like no New Yorker proclaims how much he loves his wife in public. If he does, we know he’s cheating. And Paul came in to the paper, and I was there, and I saw him walk to his desk, sit down, and write the story of her life and death. Then he checked what was going in the paper and went home. It was a lesson to me as a kid that you can’t escape personal tragedy. And my guy, when he gets the news, he knows that he has to put out the paper too. It’s two murders at a good address, and that’s one of the staples of tabloid journalism.

Читать дальше