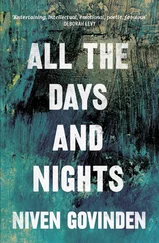

We all have our secrets.

Kel makes me walk on air and I start forgetting the real things. It’s gone eleven at night when I realise that Mum hasn’t washed my kit. Or any other clothes at all. I’m half asleep when I work this out; one of those late-night flashes that hits you before nodding off, gets you out of bed and staggering about the utility room with your eyes shut.

Mum is watching TV and says she won’t help.

‘I’m moving on,’ she goes. ‘I can’t be your maid for ever. You’re going to have to learn to take care of your own laundry.’

There’s an empty bottle of wine on the coffee table, one of the pocket ones, so I ain’t too worried. I’m not casting aspersions, I’m just saying.

‘Watch what you’re doing with the washing liquid. Don’t overfill the machine like last time. If you make a mess, clean it up.’

‘Okey-dokey, lemon-cokey.’

When she’s in this mood, it’s pointless trying to argue.

The reason for the wine bottle and the mood is this:

Mum has decided it’s been long enough since Dad. We’ve been here before, eight months after he ran to Germany with the optician slut, when she said quite resolutely it was time to move forward, but she hadn’t reckoned on the fear taking her over. Ever since Dad left it’s only ever been the two of us.

This time there seems to be more weight behind it. Far from coming out of the blue, it’s been on her mind for a while; something to do with one of the younger doctors at the health centre fancying her. He wasn’t her type, but did something to remind her that she could still cast a spell if she put her mind to it.

She doesn’t tell me this obviously, our open relationship only works one way, but I overhear her on the phone to Jason’s mum one night. Billie was distraught because she’d spent all afternoon chucking her guts up and needed to talk to someone about it. Listening to one-sided phone calls is amazing. If you can concentrate hard enough, you can pick up just about everything. It’s something Moon taught me. She’s an expert at it.

Dad’s also been threatening to come by for a visit, which may also explain Mum’s spring cleaning of self. Bored of life in the Black Forest or wherever the fuck he lives in Germany. Wants to come and bond with his firstborn. A solo trip; new wife staying at home with the kids. Twins, aged five. Killer time manager, my father.

This will be purely a father/son thing, the first time for about three years. He doesn’t want to make a big fuss, and he’s right not to. For once in his life, he’d judged the mood correctly. I’ve got no intention of seeing him.

Mum gets herself in on a speed-dating evening in town with another district nurse, one of the showy younger ones who’s always down the pub, and persuades Billie to go with them. It’s being held at Po Na Na, the smartest bar we have, and also the slimiest. Mum dresses up to the nines, long black dress, feathery shawl, heels. Hair piled up so high that you know she ain’t messing. Face made-up by her mate at the House of Fraser counter two hours earlier. I’m left to fend for myself for the evening. Kel comes round and I get lucky. So does Mum by the look of her. Her face is flushed. She tries to tell me off about not clearing up the snacks after Kel’s left, but can’t help grinning; keeps putting her hand over her mouth to giggle whenever I ask her how the night went. She got numbers, two of them, but won’t tell me any more than that.

I hate this trend for skirting around issues. I don’t see the point. Mum’s prone to procrastinate. She knows which tube of toothpaste she wants, but picking the lottery numbers can take most of the afternoon. I’m the other way, happy to charge into anything. Something I picked up from Dad. He’s the master at it. He upped and left the country the moment he’d poked the homewrecker optician and got serious. It’s the reason I hate him, but if it were anyone else I’d admire his style. I suppose it’s like this with any parent. Feelings change from one day to the next.

Coming straight to the point, cutting the bullshit, is one of the few similarities between us. Correction, a similarity I remember being between us. I haven’t seen him for so long I don’t know what he’s like any more.

So at next training, I’m ready to grill Casey about what he was doing at Britney with that random kid. It said on the news last year that the subject of Casey’s investigation was eleven or twelve, but this kid looked way younger. Either he is a half-pint, or he’s really eleven and I’m growing up too quickly for my own good.

It had been on my mind all night. I thought about txting him when I got in but knew it would spook him to know he’d been spotted. Had this feeling it would make him clam up. Dad’s approach was far better. Direct questioning never fails. Even if he’s lying to me, I’ll be able to see it in his eyes.

I get to the park at half-five and warm up, flex. Get through all the preliminary business so that I’ll be ready for him. Six passes and no sign of Casey. Six-fifteen, nothing. Six-thirty, footsteps, but only the park-keeper checking to see that I’m not making mischief (he was the one who caught me breaking out of Harriers last summer). Because it’s early and I never need it, I’ve left my phone charging in my room, the battery having been worked to its last nerve.

Casey plans each session in advance so I pretty much know what I have to do. I set myself exercises based on whatever he’s been threatening the day before. Today it’s starting block technique into the first fifty metres, and I get on with it in the hope that he’ll turn up sometime soon.

‘Stop slacking, V-pen. Don’t think you can put in only fifty per cent just because I’m not here to check up on you, Mr V-pen.’

He’s caught me making a balls-up in the starting block. Dammit. I look at my watch, six fifty-five.

‘What’s with the time-keeping, fruitcake? Thought this was meant to be a full-time gig.’

‘Enough of the cheek, young Turk. Get back on those blocks and let me see what you think’s the correct starting position. Then we’ll compare notes.’

When he’s in this mood there’s no messing with him. He throws down his trackie jacket, red and white, and we get down to business. I suppose that’s why I hired him the first place, because I wanted some seriousness. All this other foolishness is an added extra.

I only get the chance to quiz him once training’s over. We’re walking up the path towards the car park. Park-keeper hasn’t cleaned up the dog shit from yesterday so every step smells foul. He’s in an awful good mood about something, telling me some story about a notorious Surrey ref who’s as blind as a bat and giving examples of his various fuck-ups. We’re both holding our noses and laughing, and he pats me on the shoulder as we walk. Only once, only lightly, but a pat nonetheless. If I wasn’t so secure I’d be screaming for Childline about now.

‘You never did tell me why you were late,’ I go, as he’s getting into his car, glad for some distance. ‘If I was fifty-five minutes late for training, like you were, you’d bust my fucking balls.’

‘I hear that, V-pen, sir, and I sincerely apologise. I’ll fix my alarm clock and promise it won’t happen again.’

‘This training thing works both ways, Casey. Neither of us can afford to be late.’

He laughs at that.

‘Shouldn’t I be the one telling you that?’

‘Not really, since I’m the talent and you’re the help.’

Spoken like my father’s son. He’s a bastard about status, something to do with him being a Tamil and never having had any to begin with.

Читать дальше