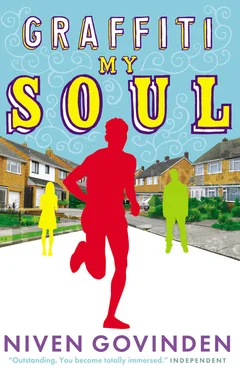

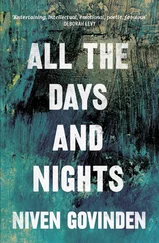

Graffiti My Soul

by

Niven Govinden

My problem is that I can’t see myself before the funeral. Really, nothing. Moon’s the one who’s dead, and I can see her clearly. I thought it was supposed to be the other way round. I’ve seen those TV shows where a boyfriend or girlfriend kicks it. The one that’s left behind bawling alone in their room. How they can’t remember their loved one’s face and all the rest of it. Even though they’ve only been cold for about a day. Then they start dragging the pictures out in desperation, or begin to construct their head out of clay. That ain’t my style. I was never one for marking every moment with a snap. Never needed to. Moon’s got the sort of face that’s hard to forget. She’s not the one I’m worried about. It’s my head that needs moulding.

I know how I looked on the morning of the funeral. Black suit from M&S that isn’t one of the old-fashioned ones. Taken-up hems on the trousers, which Mum had stayed up past midnight to do, after she’d finished her paperwork. Two-button jacket that fitted just right across my shoulders. Made me look older than fifteen. Even in that tight moment when I was certain I was feeling nothing, I knew that I was carrying off that suit. I looked tall, and lean, and sharp. If you had been walking down the street that morning, and saw me in that suit, you would have thought I was on my way to a graduation or something. There’d be no chatting about a kid who’s off to bury the girl he’s just helped to put away.

Moon would have died if she’d seen me in that suit. Bad joke, but I’m too young to be owning this stuff. I should be wearing it when I’m, like, eighteen. I can see it now. A Friday night, me in that suit, her winched out of her jeans and into one of those dresses from Karen Millen that cost too much. We’d go into Kingston, where they’d let us into Oceana without a word. Drinking cocktails and dancing stupid to garage. We could have killed it. Again, bad joke. That’s the only thing I seem to be good at right now, cracking the bad ones. (Not even able to crack one off.) Alone in my bedroom. All dressed up and no Moon to see it.

This is the morning after the funeral. I put the suit on again once Mum has left for work. She takes her time, pretending to forget something in the bathroom so that she can pace past my door three or four times. Listening out for signs of life or death. Before Moon started to change things were easy enough and there was none of this pacing. I know Mum’s thinking about me, fretting over how things have ended up the way they have, but I haven’t got time to worry about her on top of everything else. I just don’t.

I can’t get myself to look how I looked yesterday. Skin paler, bags under the eyes blacker. Jacket doesn’t sit so smart. Pre-pressed trouser seams flap at my bare feet needlessly. Same suit, different look. I don’t understand it. But then I think that maybe it’s because I’m indoors that I don’t feel right.

When I walked to the church yesterday — there was no way I was sharing a car with Moon’s parents and Gwyn — it was the first really bright strong day of spring, and the sun was doing its I’m-back-and-bad dance. I took the back roads so that I could walk past the ropey on the way. The original ropey that’s in the middle of the wood, not the new one by the church that the younger kids use. It had only rained lightly during the night, so the ground was good to firm. If you looked close enough, because you couldn’t catch them from a distance, bare branches were just starting to peep pea-pod green from their tips. Birds were there, but distant, I didn’t pay much attention. It was mainly me on that walk, crunching dead wood underfoot, the sun, and the trees with their woosh woosh woosh. Taking my time, because I knew they’d have to wait for me.

Everything in that moment felt good. The sun was teasing the top of my head and I felt that some kind of thing was finally going to let itself out. That maybe I’d get through this. I didn’t quite manage the sigh, but the feeling that it was coming got me through the day. Even Moon wouldn’t have taken the piss out of the effort I was making. I didn’t let her down. I delivered.

And I don’t use these words lightly. When she was around, we never said these things about each other. Why would we? Why would we even notice them? There’s plenty of time to learn these things later. We’re fifteen. This life’s supposed to be infinite.

So now I’m walking down the street in the suit again. T-shirt instead of a shirt, the first hat I can find, and trainers. It’s not quite as yesterday, but it’s the best I can manage. Not that it matters particularly; it’s a loose experiment. The light’s no good down our road. Too many semis on top of each other. It’s no wonder I can’t get over anything in an environment like this. This place is no Mecca for healing. No comfort to be had in pebble-dashing and crazy paving.

As I turn the corner into Elm Drive, then left into Oakdene, and then into Broadhurst, where the wood lies at its very bottom, I drop the shuffling, and my steps become firmer and faster. By the time I’ve passed Jason’s house — number 32 — I’m breaking into a run. The sun is nowhere near coming out. Everything is flat and grey. Trees look beyond growth. I can’t help seeing death in everything. I’m not special in this suit. I look like an idiot who’s very much under eighteen, and unsure of himself. A little boy who needs someone to hold his hand. How was it that everyone took me seriously yesterday — looking like this?

Broadhurst is used as a rat-run during rush hour. If you drive all the way down the hill you can cut past the one-way into town, but at this time of the morning it can be deathly quiet. Another bad joke, and an inaccurate one. Everything about Moon’s going has taught me that there’s nothing quiet about death. Kicking and screaming to the last. Pressing against my ears until all other sounds are shut out. Singularly louder than anything I’ve ever heard.

There’s a car coming now, can’t quite make out what, and it slows on my side. Someone with a blocked nose shouting from the window as I carry on running towards the wood. Maybe I was careering into the road, it has been known to happen. I’m moving forward, that’s all I know.

‘Hey! Hey! Where are you going? Hey!’

52, 54, 56, 58, 60, 62, 64, 66, 68, 70. The road ends at 284. Sun now decides to make an entrance. Coming out from the clouds in full effect, blinding from the right. It’s handy. I don’t make eye contact with the car. Instead keep running, keep focusing on the numbers. You hear about all kinds of nutters these days, accosting kids.

‘Come back! I just want to know where you’re going!’

The car isn’t leaving. I should have brought my bike. They wouldn’t have seen me for dust then.

‘I don’t want an argument,’ calls the blocked nose again, loud enough so all of Broadhurst can hear how odd they are.

I think about heading back to Jason’s house. He smoked his way back to reality after his sister was in a hit and run. Twenty blunts a day at the worst point. Once the front door opens and he comes staggering out, I wouldn’t be bothered then. But the wood appears as the street dips into the hill, and the whoosh whoosh hits the back of my ears. A final incentive. I pick up a gear, and break into an all-out sprint. I’m the fastest at school. 100, 200 or 400m, take your pick. There’s not one fucker who can touch me. Lynford Paki they call me when I’m on one. 132, 136, 144. I reckon I’m at touchdown in about thirty seconds. Ain’t no one going to be bothering me then.

Читать дальше