“Borrow ’em, sure. Why don’t I see if can find the negatives.” She opened a drawer in which negatives were under such pressure that some of them sprang out and fluttered to the floor. She left them there while, on second thought, she opened a tin of butter cookies and arranged them on a painted plate. Renée held her glass of Amaretto to the graying light in the window. A label on the bottle said According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects .

“I have to go,” she said.

The sky was deepening as if the land were on a slope and sliding towards a precipice. In the parking lot of an office complex affording a good view of Sweeting-Aldren, she sat on the hood of the Mustang with the Caddulo pictures and a 7 1/2-minute USGS topo map, comparing perspectives on a cooling tower, trying to triangulate a location for the derrick. Thousands of pig-sized and cow-sized boulders, some of them possibly glacial and native, shored up the hillside on which the complex stood.

A voice spoke from right behind her: “What ugly children.”

She turned and weathered a spasm of fright. Rod Logan was standing by the car, holding a picture that had been lying on the hood.

“Give me that,” she said.

Behind her in the parking lot, junior executives were walking to their shiny cars. Rather than risk a scene, Logan handed her the picture. He strolled to the brink of the asphalt and peered down at the yellow pond below the boulders.

“You know,” he said, “in the old days, people like you, they’d come around, they’d get warned, and if they kept coming around they’d have the shit beaten out of them, and nobody would really complain or litigate, it was just part of the way the game was played. But everybody’s gotten so gosh-damed kind and gentle lately. It’s reached a point where all I can really do is ask you politely to clear out, and if you choose not to, we’re no longer on terra firma, if you know what I mean. We don’t know what kind of procedures are required. There’s no literature on it.”

Renée got in the car.

“This is quite the stylish car, incidentally. Nice duds, too. Looks like you’ve found a wealthy patron.”

She started the engine. Logan leaned over her, looking straight down on her lap.

“Goodbye, Renée.”

She made another trip to the Square, stopping at the clinic in the Holyoke Center and then dropping off the Caddulo negatives for enlargements. The rest of the weekend, late into both nights, she worked at a console in the lab. Not a single person disturbed her until Sunday afternoon, when a few students drifted through, said hello, executed Diane, etc. No one looked at what she was writing.

Her abstract read:

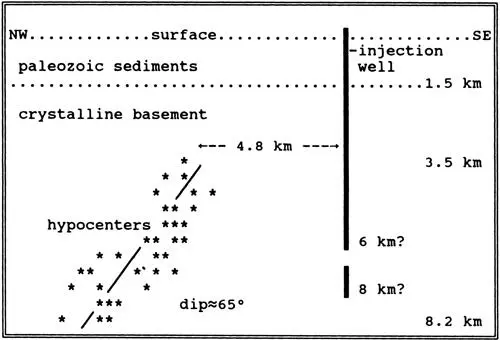

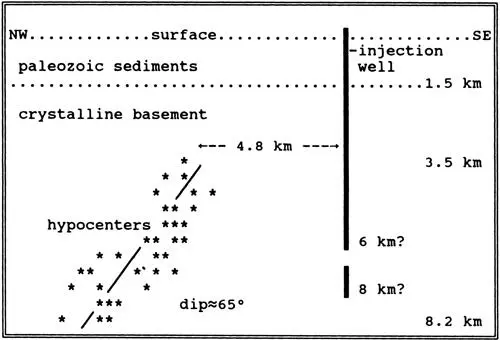

Recent seismicity in Peabody, Mass., and the prolonged sequence in 1987 have displayed the swarm-like character of known instances of induced seismicity. Until now the resemblance has been disregarded because of the relatively great focal depths of the earthquakes (3-8km) and the absence of reservoirs and injection wells in the focal area. However, photographic and archival evidence strongly indicates that in 1969-70 Sweeting-Aldren Industries of Peabody drilled an exploratory well to a depth in excess of 6 km, and that the well has subsequently been used for waste disposal. Current research locates observed activity on a steeply dipping basement fault striking SW-NE. Models of fluid migration and fault activation are proposed, the temporal distribution of observed seismicity is explained, and the legal implications of Sweeting-Aldren’s role are briefly discussed.

She described the tectonic environment of the Peabody earthquakes. She marked likely well-sites on the best of her aerial photographs. In footnotes she mentioned Peter Stoorhuys and David Stoorhuys by name. She made pictures:

She wrote that the absence of earthquakes between 1971 and 1987 indicated that there were no stressed faults in the immediate vicinity of the injection well. It had taken as long as sixteen years for fluid to be forced far enough into the surrounding rock for it to reach the fault(s) on which the earthquakes were taking place. This indicated that very significant volumes of waste had been injected, and that the rock formation at a depth of 4 km was loose enough to accept this volume at pumping pressures low enough to be commercially attractive. The conventions of scientific prose served to clarify and heighten the passion with which she wrote. She was so absorbed in her arguments that it shocked her, at the mirror in the women’s bathroom on the second floor, to see the expensive, tarty clothes she was wearing.

Monday afternoon, after sleeping late, she picked up the Caddulo enlargements, bought some red nail polish, and stopped by the Holyoke Center again. Back in Hoffman she saw a flabby, sunburnt woman standing in the hall outside her office, looking very lost. Brown daisy-shaped pieces of felt were sewn onto the chest of her yellow sweat suit and the thighs of her yellow sweatpants; a button pinned to her shoulder said adoption not abortion. Renée had heard that people like this were still dropping in from time to time, but she hadn’t seen one personally since the week her phone and mail harassment started.

The woman sidled up to her and spoke confidentially. She had a twang. “I’m looking for a Dr. Seitchek?”

“Oh,” Renée said indifferently. “She’s dead.”

“She’s dead!” The woman drew her head back like an affronted hen. “I’m very sorry to hear that.”

“No, I’m joking. She’s not dead. She’s standing right in front of you.”

“She is? Oh, you. What’d you say you’re dead for?”

“Just a joke. Let me guess what you’re here for. You came to my abortion clinic to complain to me personally.”

“That’s right.”

“Clairvoyant,” Renée said, touching her temple. She saw that Terry Snall had stopped at the bottom of the staircase. He had his hands on his hips and was exuding tremendous discombobulation over the way she was dressed. She turned her back to him. “Let me ask you,” she said to the visitor. “Does this building look to you like an abortion clinic?”

“You know, I was just wondering that myself.”

“Well, you see, it’s not. And I’m not a medical doctor. I’m a geologist.” On an impulse, she spun and pointed. “Terry, though. Terry performs abortions. As a sideline, don’t you, Terry?”

“That’s not funny, Renée. That’s not at all funny.”

“He denies it,” she explained, “because he doesn’t want you to harass him. But he’s part of the whole — abortion — conspiracy.” She hugged herself tightly, turning one shoe on its heel. There was an awkward silence, disturbed only by the whining of the line printer behind a closed door.

“Well,” the visitor said. “She already lied to me once. She said she was dead!”

“That’s what Renée is like,” Terry said. “She thinks she can do anything she wants. She thinks she’s a cut above.”

Renée spun again, still hugging herself. “But that’s because I can do anything I want. And I’m going to, Terry! You watch me.” She approached the woman, who, though she was bigger and taller, took a wary step backward. “Where are you from?”

“You mean originally? I’m from Herculaneum, Missouri. But I live in Chelsea now.”

“You belong to Stites’s church.”

“The Reverend Stites.”

“The Reverend Stites who claims he has nothing to do with phone and mail harassment.”

“Oh, he don’t, see.” Oblivious to having let the word “harassment” pass, the woman unzipped her swollen beige purse. “This letter here I got forwarded from Herculaneum.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу