“That’s not Santa,” said Radar, and then hid his face in Kermin’s jacket. “Santa has a beard.”

“No, I’m sorry to report that I’m not Santa. He was otherwise engaged.” The man smiled, extending his hand to Charlene. “Leif Christian-Holtsmark.”

“We weren’t sure if. .” she trailed off.

“If I existed? I do. I very much do. My apologies,” said Leif, turning. “And this must be the famous Radar. How old are we, little man?”

Radar burrowed into Kermin’s jacket.

“How old are you, Radar?” said Charlene.

“Dis many,” said Radar, holding up a hand that showed a varying number of fingers, anywhere from two to five.

“He’s four.” Charlene apologized. “He knows he’s four, but he seems to insist on presenting a range of choices.”

“It’s understandable. One can never be sure,” Leif said, and laughed. “But four years old! Now, that is something. Well, Radar, velkommen til Finnmark. You are now on top of the world.”

He drove them in his battered Land Rover out into a light boreal forest of pine and downy birch. The road hugged the bank of a fjord and then turned onto a small dirt track that wound around several kettle-hole lakes thick with summer algae. The trees began to thin, and they found themselves on a long, flat plain.

“We are right on the edge of the tree line,” Lars explained. “To the north is tundra, to the south is the great taiga, which stretches two thousand kilometers into Russia.”

The fog burned off. Charlene could see that the ground was marked by splashes of bright lime-colored lichen. It was unlike any landscape she had ever seen before.

“There,” said Leif. He pointed up to a raised kame terrace. A herd of bone-white reindeer were tracking their progress. Leif stopped the car and rolled down his window. He was silent.

“Do you hear it?” he said finally.

They listened.

“What?” Charlene asked.

“The reindeer,” said Leif. “They have their own frequency. About fifty-eight hertz. Listen.”

They listened. After a while, Charlene could hear it, or at least she could imagine hearing it. Something like a moan that had not quite escaped the lips, but rendered simultaneously by hundreds of animals. The sum of a sound never fully finished.

“Santa’s reindeer!” Radar yelled.

As if in response, several of the reindeer began to run over the terrace, and soon the whole herd, sensing some unspoken signal, was thundering away as one.

Radar looked heartbroken.

“Don’t worry, honey,” said Charlene. “It wasn’t you. They had someplace to go.”

“The Sami have a saying: ‘En rein som står stille, er ikke en rein.’ ‘A still reindeer is not a reindeer,’” said Leif. “Migration is a part of their being. To move is to exist.”

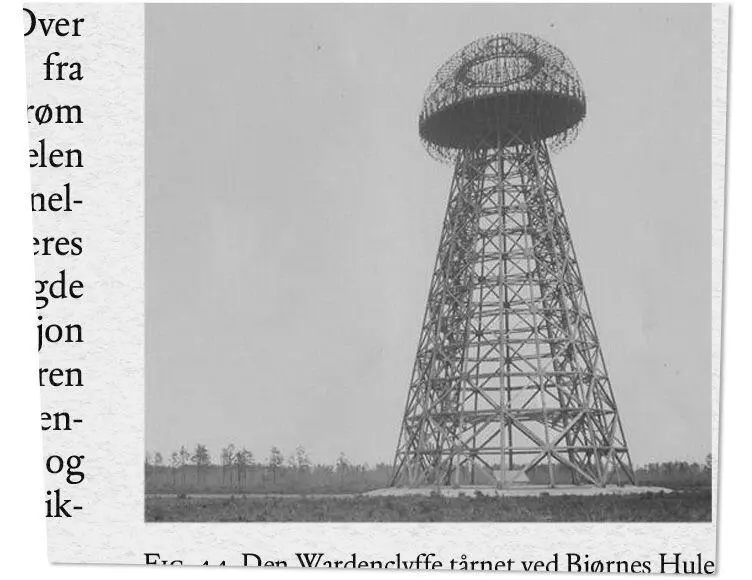

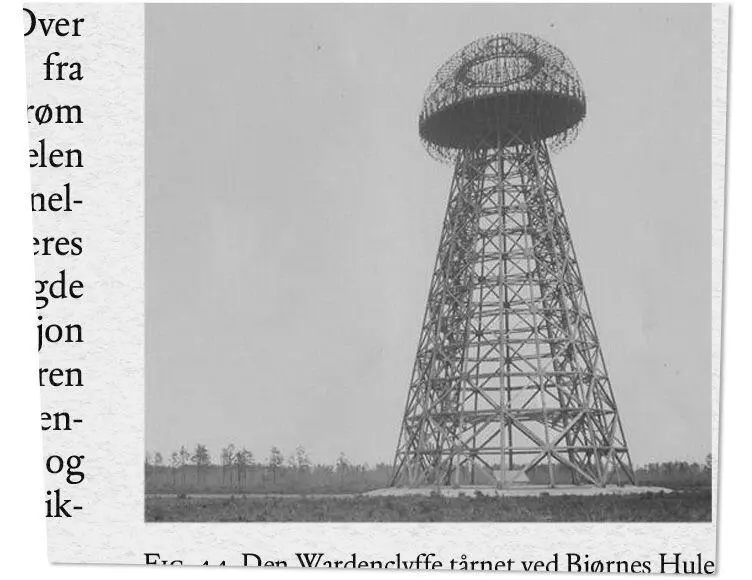

They drove further into the wilderness. Charlene noticed telephone poles running alongside the dirt track, which surprised her, given the remoteness of their surroundings. The poles carried a black cable that was as thick as a grown man’s leg. Gradually, a tower became visible in the distance. The top of the tower was bulbous; it looked like a mushroom-headed rocket ship.

Fig. 1.3. The Wardenclyffe Tower at the Bjørnens Hule, Kirkenes, Norway

From Røed-Larsen, P., Spesielle Partikler, p. 148

“What is that?” asked Charlene.

“It’s our Wardenclyffe tower,” said Leif.

“What’s a Wardenclyffe tower?”

“Nikola Tesla invention,” said Kermin, craning his head to get a look. “It makes free electricity for whole world. But how did you do this?”

“So you know about Tesla?” Leif said into the rearview mirror.

“Of course. He was Serb,” said Kermin.

“And a poor businessman. But he was also the greatest mind of the last two hundred years.”

“Wait — free electricity for the whole world?” said Charlene. “Is that even possible?”

“Yes, well, it’s all in theory right now,” said Leif. “But Tesla’s design was quite genius. The towers use the earth like a battery, drawing electricity from deep currents—”

“Intra-crustal telluric currents,” said Kermin.

“That’s right.” Leif paused. “And then the tower transmits this current through the atmosphere. The idea is that everyone has a small antenna on their roof and receives their electricity almost like a radio wave—”

“How deep into ground do wires go?” Kermin interrupted.

“Three hundred meters.” Leif smiled. “Deep enough.”

The road ended at the base of the Wardenclyffe tower, where there was a cluster of a dozen or so traditional wooden lodges with sod growing on the roofs. Lying between the buildings were large piles of mechanical equipment — ten-foot diesel engines and generators and strange, loop-de-loop electrical transistors. Wires ran from each house into the tower, then back into the transistors, then into totemlike wooden carvings of animals frozen in ferocious poses, their eyes replaced by lightbulbs. They disembarked from the jeep and stood, blinking.

“Welcome to home base,” said Leif. “We affectionately call it the Bjørnens Hule, or ‘the Bear’s Cave’ in English. We’re somewhere between the Finnish-Norwegian border.”

“What do you mean, between ?” Charlene asked.

“Borders are complicated up here. Especially now. The Cold War has made everything a bit testy. You can’t spit near the Russian border without being picked up. But borders are not natural things. Birds do not listen to borders.”

“But we’re in Norway now?”

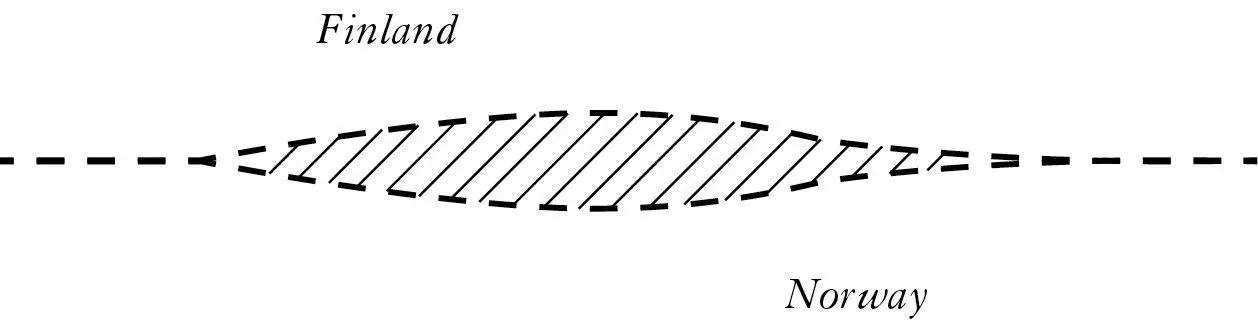

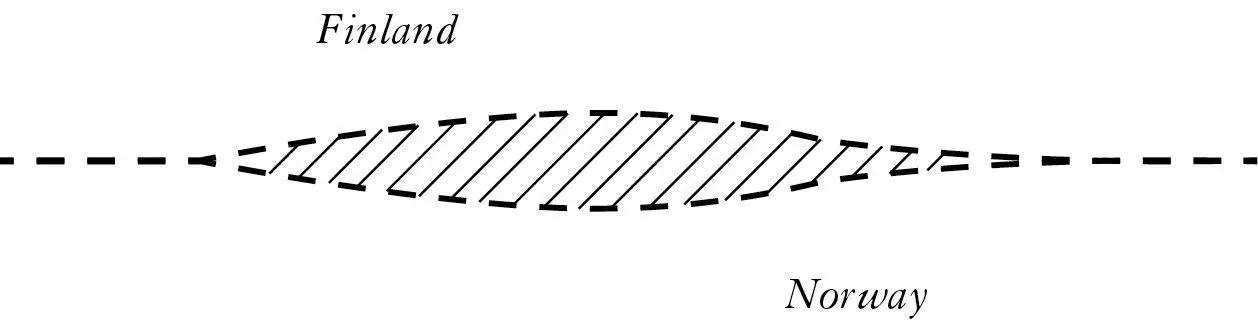

“Well, something strange happened. A cartographer made a mistake. The Finns thought the border was one line, the Norwegians thought it was another. Normally when this happens you get a big argument and maybe a war or two because someone is claiming too much, but, typical Scandinavians, both countries have claimed too little. And now there’s a space, like this.”

He used his fingers to demonstrate:

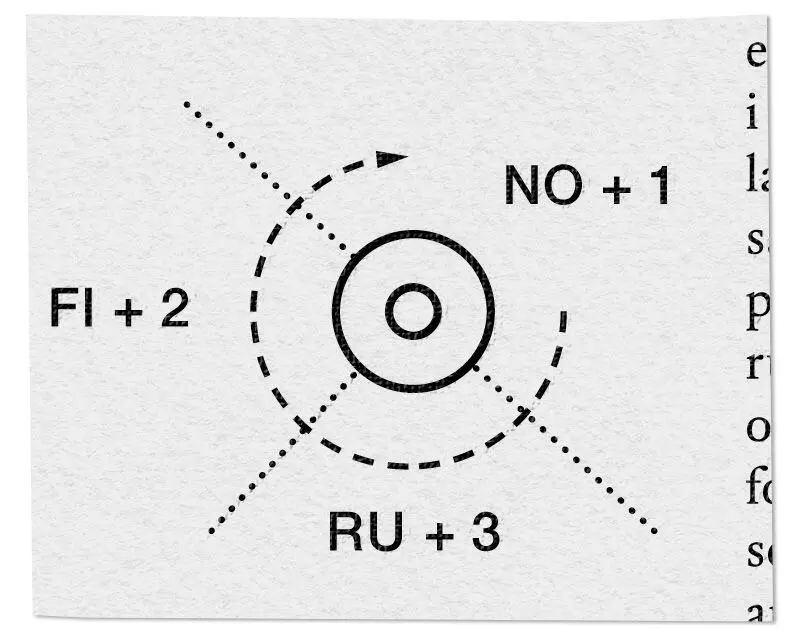

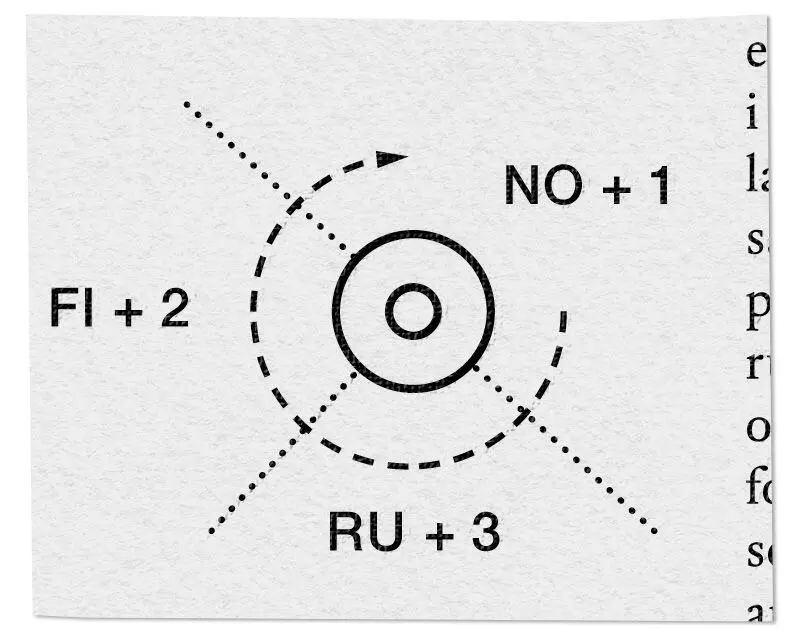

“It’s where we get our emblem. The eye.” He pointed at the base of a totem pole, where a stenciled eye watched them without comment.

“Over there,” he said, waving his hand vaguely, “is the Treriksrøysa. A point where Norway, Finland, and Russia all come together. You aren’t allowed to walk around this point fully, like this,” he said, promenading his fingers, “because you would violate international law. Wandering in and out of countries. But how about this: at this point, if such a point could even exist, time fluctuates . Norway is on Central European time, Finland is on Eastern European time, one hour ahead, and Russia is on Moscow time, two hours ahead. One point, three times. How can that be? And yet we’re okay with this being true.”

Charlene looked at her watch, suddenly feeling as if she were losing her bearings.

“What time is it right now? I forgot to set my watch.” She fiddled with the dial, spinning the hour hand forward.

He shrugged. “In the summer, when the sun never sets, time becomes quite relative.”

“Twelve thirty?”

Читать дальше