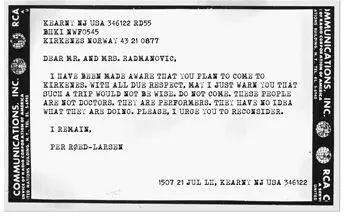

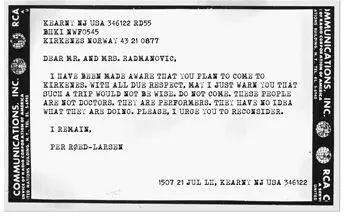

“Wait. What is this?” Charlene said, holding the envelope up. A shy but curious Radar was peeking out from behind her leg.

“It’s a telegram, honey,” the man declared, as if this were the most obvious fact in the world. Then he tromped down their steps and mounted his bicycle, which he had left lying across the sidewalk, leaving Charlene to stare in wonder.

“What’s a telly-gram?” Radar asked when they were back inside. “A letter?”

“It’s like a letter,” she said. “But it’s sent by machines.”

She would’ve thought it was all a dream if not for the envelope still in her hands. She brought it to her nose. The paper smelled of oily, metallic parts and oddly. . cinnamon . Telegrams were confusing documents. Their words had traveled great distances, and yet the physical paper had not. This cinnamon scent was Jersey-borne.

She opened the telegram in the kitchen.

Per Røed-Larsen. The name seemed oddly familiar.

“What dat machine say?” Radar asked.

“It said — well, I’m not sure what it said.” She flipped the telegram over, but there was nothing more.

• • •

THAT EVENING, while they were watching television, Charlene brought out the airplane tickets.

“I didn’t ask for these, I swear. I just asked for some more details,” she said. She sat down on the floor in front of his armchair.

He scrutinized the tickets for a long while, turning them over in his hands as if he were judging their authenticity.

“But isn’t that nice of them? They’re paying for us to come. It must be expensive.” She was readying herself for his explosion — to pounce on him in case he decided to try and tear up the tickets.

“I was in Norway once,” he said after a while.

“Yes,” she said, brightening. “It might be nice for you to go back.”

“I don’t need to go back,” he said.

She placed a hand on his foot. “Kermin.”

A silence.

“You really want this?” he said.

She nodded.

“Just to talk to them?”

“Just to talk.”

“And then you are okay?”

“And then I’ll be okay.”

“And then no more?”

“No more.” She shook her head. “After this, no more.”

“You promise?”

“I promise.”

“All right.”

“All right what?”

“We can go.”

“Oh, Kermin!” She jumped up, hugging him, kissing his rough cheek. “We’re just going to find out, I swear. Nothing more. I’ll feel so much better then. And I was doing a little bit of reading. It’s supposed to be really nice in the summer. Land of the midnight sun and all that.”

She did not tell him about the telegram. In truth, she did not know what to make of it herself. So she decided to act as if she had never received it. She hid the telegram in the utility drawer. But soon the drawer felt as though it could no longer safely contain such a document, so she hid the telegram beneath a floorboard in their bedroom that she had pried loose with a hammer. Inside this hole she also put a binder of newspaper articles she had collected about Radar’s birth. And the clipped ad for the IFAC flavorist position that she had stashed away in the recipe booklet. When she could not think of anything more to put down there, she hammered the floorboard back into place and covered it with a rug from another room.

Kirkenes turned out to be about four hundred kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, the last town in Norway before the Russian border. On the flight from New York to Oslo, they watched an overexposed screening of Days of Heaven, in which a man murders his boss in a steel mill and then flees with his wife and daughter to the wheat fields of the Texas Panhandle, only to murder his boss again. At least this is what Kermin thought that the movie was about. There was no sound in his stethoscope-like headset, and he was at a bad angle to watch the dreamy images of the wheat fields burning. There was something uncanny about flying over an ocean while watching wheat fields burn. He looked out the window, trying to catch a glimpse of the ocean that he had once escaped across in the hull of a boat. It was hard to imagine that the small layer of blue far beneath them was the same sea that had borne him to the New World.

Maybe sea and land were not altogether different, he thought, touching the cold glass of the airplane window. Only a small matter of density.

Inside the clean and empty Oslo airport, they blearily drank a coffee and thumbed through a rack of chunky Telemark sweaters before catching a toothpaste-colored prop plane up to Kirkenes. People in line to board the plane stared openly at Radar, until Charlene glared at them, and then they stared at everything but Radar.

The airplane sputtered and bounced against the hidden pockets of turbulence that lay sleeping above the Kjölen Mountains. Radar threw up twice. The Norwegian stewardess smiled as she took the wet airsick bag from Charlene.

“Poor boy,” she said. “He is so far away from home, yes?”

They came down in a sea of fog. The airplane descended and descended, and suddenly there was the tiny airstrip. The sun glowing dimly from somewhere behind that suspended scrim of moisture. They collected their bags directly from the plane. Under a light breeze, the air smelled sweetly of wet moss. The handful of other passengers made their way into cars and a small bus headed for town, leaving them alone inside the one-room terminal but for a janitor mopping at a floor that looked as if it had already been cleaned.

“They are meeting us here?” Kermin asked.

“That’s what they said.”

“There’s no one here.”

“I can see that, Kerm. Maybe they got the time wrong.”

But as she stared out at the fog rolling in waves across the runway, she knew that no one was coming to meet them. There was no such thing as Kirkenesferda. There were no scientists and artists experimenting with electricity up here. There was only tundra and fog and an invisible sun that never set.

“This is Santa Claus house?” she heard Radar say.

“No,” said Kermin. “Santa Claus does not live here.”

“Jesus Christ,” she whispered to her reflection. Her shoulders slumped. They had come this far for nothing.

There was nobody at the ticketing booth. Charlene walked up to the janitor swabbing at the pristine floor.

“Do you know when the next flight to Oslo leaves?” she asked loudly.

To her surprise, he spoke perfect English. “Five hours, ma’am. If the weather doesn’t get worse.” He looked at Kermin and Radar, sitting on a bench. “Didn’t enjoy your stay?”

“No, no,” she said, embarrassed. “It’s beautiful. There’s just been a mistake. A mix-up. We weren’t supposed to come.”

He nodded. “Same thing happened to me. I’m Swedish. I came here for a woman, but the woman left. I ended up staying. Twenty-five years.”

“Is there someplace we can wait?” she asked.

He looked around the room, as if to indicate that this was the extent of the known universe.

It was at this point that a man in a yellow jumpsuit came dashing into the terminal. He appeared quite frantic, but when he saw them, his expression dissolved into relief.

“I’m so sorry I’m late,” he said, coming up, breathless. “There was a little problem at the office.”

The man was hairless — completely bald, no eyebrows. Charlene guessed he was in his late sixties, though his light blue eyes remained young and bright.

“You’re Leif?” said Charlene. He was wearing knee-high mucking boots over his yellow jumpsuit, giving the impression that he had just skydived into a manure field.

Читать дальше