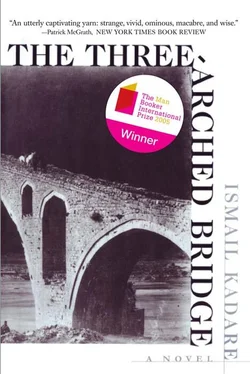

Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Three Arched Bridge

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Arched Bridge: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Three Arched Bridge»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Three Arched Bridge — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Three Arched Bridge», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

18

THE SECOND MONTH OF AUTUMN was cold as seldom before. After the first flood, the waters of the Ujana e Keqe cleared and reverted to their usual color, between pale blue and green. But this color, familiar to us for years, now seemed to conceal cold fury and outrage.

The laborers, laden with stones and buckets of mortar, moved like fiends among the planks and beams. The river flowed below, minding its own concerns, while the workmen above minded theirs.

Throughout October nothing of note occurred. A drowned corpse, brought by the waters from no one knew where, collided with one of the central piers, spun around it a while, and vanished again. It was on that very day that there dimly emerged from among the mass of scaffolding and nailed crossbeams something like a bow connecting the two central piers. Apparently they were preparing to launch the first arch.

19

ON THE THRESHOLD OF WINTER, along with the first frosts, wandering dervishes turned up everywhere. They were seen along the high road, by the Inn of the Two Roberts, and farther away, by the Fever Stone, Travelers arriving from neighboring principalities said that they had seen them there too, and some even said that Turkish dervishes had been seen along the entire length of the old Via Egnatia. Sometimes in small groups or in pairs, but in most cases alone, they ate up the miles with their filthy bare feet.

Early yesterday morning I saw two of them walking with that nimble gait of theirs along the deserted road. One led the way, the other followed two paces behind, and I looked at their rags, so soiled by the dust and the winter wind, and asked almost aloud, “Why?”

Who are these vagrants, and why have they appeared throughout the peninsula at the same time, on this threshold of winter?

20

FROST COVERED THE GROUND. Two wandering bards had stayed three consecutive nights at the Inn of the Two Roberts, entertaining the guests with new ballads. The ballads had been composed on the subject of the Ujana e Keqe and were inauspicious. What you might call their content was more or less as follows: The naiads and water nymphs would never forget the insult offered to the Ujana e Keqe, Revenge might be slow., but it would come.

Such ballads would be very much to the taste of the people from “Boats and Rafts*” Yet now that they had lost their battle and the bridge was being built, not one and not a thousand ballads could help them, because so far no one has heard of songs destroying a bridge or a building of any kind.

Since their final departure, defeated and despondent, the “Boats and Rafts’, people had been seen no more. They seemed no longer of this world, but now the ballads at the Inn of the Two Roberts reminded me of them again, Had they given up the fight, or were they biding their time?

Meanwhile the Ujana e Keqe looked more askance at us than ever, or perhaps so it seemed to us because we knew of the stone clasp placed over it.

21

AS THE SEASON DREW TO AN END, our liege lord invited distinguished guests to a hunt in the Wolf’s Wilderness, as he did every year at about the same time. Besides neighboring lords and vassals, Gjin Bue Shpata, the powerful overlord of southern Arberia, also came. The two sons of old Balsha, Gjergj Balsha and Bal-sha II, came from the north together with their wives, the countesses Mari ja and Komita. They were followed by the lord of Zadrima, Nikollé Zaharia, whose arms bear a lynx, and the barons Pal Gropa, lord of Ohri and Pogradec, and Vlash Matranga, lord of Karavasta, as well as another lord, whose name was kept secret and who was said only to be a “man of note in the Great Mountains,”

As in every year, the hunt was conducted with all the proper splendor. Hunting horns, horses, hooves, and the pack of dogs kept the whole of Wolf’s Wilderness awake night and day. No accidents occurred, apart from the death of a stalker who was mauled by a bear; Nikollé Zaharia sprained his ankle, which particularly worried the nobility, but this passed quickly.

The good weather held. At the end of the hunt, soft snow began to fall, and the snow-dusted procession of hunters on their homeward journey looked more attractive than even

Nevertheless, as 1 looked at them in their order, a spasm seized my soul. The emblems and signs on the noblemen’s jerkins, those wild goats, horns, eagles” wings, and lions’ manes, involuntarily reminded me of the drowned animals that the Ujana e Keqe had so ominously carried down the gorge. Defend, oh Lord, our princes, I silently prayed. Oh, Holy Mary, avert the evil hour.

The guests did not stay long, because they were all anxious to return to their own lands. During the three days that they stayed in all (less than ever before), we expected to hear of some new betrothal, but no such thing occurred. In fact, the guests held a secret discussion about the situation created by the Ottoman threat.

While the discussion continued, the two countesses, the sisters-in-law Mari ja and Komita, came to watch the construction of the bridge. It fell to me to escort them and explain to them the building of bridges, about which they knew nothing. They were impressed for a while by the swarm of workmen that teemed on the sand, by the melee, the din, and the different languages spoken. Then Komita, who had visited her father in Vloré a month before, mentioned the anxiety over the Orikum naval base, and then the two disparaged at length their acquaintances in great houses, especially the duchess of Dürres, Johana, who was preparing to remarry after the death of her husband, and so on and so forth, finally arriving at their sister-in-law Katrina, the darling daughter of old Balsha, of whom they were obviously jealous, I attempted to bring the conversation back to the Orikum base, but it was extremely difficulty not to say impossible.

Under our feet, the Ujana e Keqe roared on with its grayish crests, but neither the river nor the bridge could hold the countesses’ attention any further. They went on gossiping about their acquaintances, their love affairs, and their precious jewelry; try as 1 might not to listen, something of their chatter penetrated my ears as if by force. For a while they maliciously mocked the Ottoman governor’s proposal of marriage to the daughter of our count. They dissolved in laughter over what they called their ‘‘Turkish bridegroom,’ imagining his baggy breeches; they held on to each other so as not to fall into the puddles in their mirth. Then, amid fresh gales of laughter, they tried to pronounce his name, “Abdullah,’ saying it ever more oddly, especially when they tried to add an affectionate diminutive “th” to the end.

22

AT THE END OF THE MONTH OF MICHAELMAS and during the first week of winter, we still saw dervishes everywhere. It struck me that these horrible vagabonds could only be the scouts of the great Asiatic state that destiny had made our neighbor.

They were no doubt gathering information about the land, the roads, the alliances or quarrels among the Albanian princes, and the princes’ old disputes. Sometimes, when I saw them, it struck me that it was easier to collect quarrels under the freezing December wind than at any other time.

I was involuntarily reminded of fragments of the conversation between the two dainty countesses, and it sometimes happened that, without myself knowing why, I muttered to myself like one wandering in his wits the name of the “Turkish bridegroom”: Abdullahth.

23

ONE OF THE NOVICES attached to the presbytery woke me to tell me that something had happened by the bridge, Even though he had gone as far as the riverbank himself, he had been unable to find out anything precisely.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Three Arched Bridge» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.