Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ismail Kadare - Three Arched Bridge» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

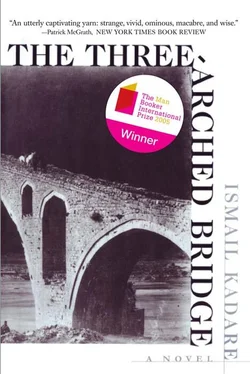

- Название:Three Arched Bridge

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Three Arched Bridge: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Three Arched Bridge»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Three Arched Bridge — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Three Arched Bridge», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

THREE DAYS LATER I watched the raft again from the porch of the presbytery, Only two goatherds with their animals were crossing. The raft made the journey several times until it had carried the entire small herd to the opposite bank, The herdsmen were wrapped in cloaks like those of all common shepherds, but their tall pointed caps made them look somehow frightening from a distance.

Another day at dawn,1 heard through my sleep some distant voices, apparently calling for help, and shouting “Ujk, ujk” — “Wolf, wolf.” I leaped out of bed and listened hard. They were really protracted shouts of Uk, oh U-u-uk.” I went out to the porch, and in the dim dawn light 1 made out four or five people on the opposite bank with a kind of black chest in their midst. They were calling the ferryman. Their shouts, stretching like a film over the swollen waters of the river, hardly reached me. It was a cold, bleak morning, and who knows what anxiety had made them set out on their road before dawn. “Uk, oh

U-u-uk,” they called to the ferryman, holding their hands to their mouths like the bells of trumpets.

Finally I saw Uk stagger down to the bank in his stooped fashion, no doubt muttering curses under his breath at these unknown travelers, the raft, the river, and himself.

When the raft drew near the opposite bank and the travelers boarded, I saw that the black object was nothing less than a coffin, which they carefully lifted onto the planks of the raft,

I went back to bed to rest a while longer, but sleep eluded me.

13

THE FIRST CONTINGENT of men and laden mules arrived at midday on the seventeenth of April. Mad Gjelosh strode out in front of the muleteers, gesticulating as if pounding a drum and puffing out his cheeks, drunk with joy.

The men and mules halted on the riverbank, just next to the designer’s empty hut. There, in the wasteland among the wild burdocs, they started unloading. This took all day. By late afternoon the riverbank was unrecognizable. It was a complete jumble; people scurried about, speaking a language like a thicket of brambles, amid the piles of planks, ladders, creeperlike ropes, stakes, cleats, and implements of every kind. There was so much hubbub that even Gjelosh was taken aback, and I rather suspect that his initial joy was dampened.

Late that evenings the new arrivals began building sheds by torchlight. That night some of them slept in the open, if such perpetual restlessness could be called sleep. They kept wandering, who knows why, from the bushes to the riverbank, calling to each other with loud voices and seeming to sing, weep, or groan in their sleep. They went boo, boo like owls, and threw up exactly over the spot where the toads were. Torches glimmering here and there gave everything the appearance of a nightmare. In fact, the anxiety and sleeplessness they brought with them were the first things they conveyed to those around them. The construction of storage sheds and dormitories went on for several days. It was surprising to see how even such rickety huts could emerge from this clutter. The disorder looked incapable of resolving itself into anything, and it seemed quite incredible that a bridge could come out of it. These road people were as rowdy and dirty as the “Boats and Rafts” people were meticulous and organized in everything they did.

By the end of April two further caravans arrived, but work on building the bridge did not begin until the designer came. Now they called him the master-in-chief, because it seemed that he himself would direct the building of the bridge. Excavations began a long way off and to one side, by the bushes, as if the bridge were to run off in that direction, as far away from the water as possible. The workmen dug all kinds of pits and dead-end ditches. Everybody labored to level the ground, far away from the water, almost as if they wanted to deceive the river: “We have nothing to do with you. Can you see how far away we’re digging? Flow on in peace.”

The network of pits and meaningless lines grew more elaborate as time passed. Everybody began to think that the master-in-chief was quite simply a little weak in the head and was frittering away the money allotted for the construction of the bridge. People even said it was no accident that Gjelosh made friends with him so quickly. It takes one to know one.

Of course, Gjelosh scampered about all day amid the confusion, puffing out his cheeks, gnashing his teeth, and pretending to beat a drum. Nobody shooed him away. Even the master’s two assistants, who were supervising the work, said nothing to him. In contrast to their master, they were garrulous and ubiquitous. One of them was powerfully built, bald, and with abscesses on his throat, which some people said were signs of an incurable disease, while others insisted that they were scars from the torture he had been subjected to in an attempt to extract his bridge-building secrets from him. Those who made the latter guess were again divided into two camps. One group said that he had not withstood the agony and had divulged his secret, and others claimed that he had endured everything they could do, arching his back like a bridge under the pain, and had told his enemies nothing.

The second assistant, on the other hand, was scrawny; everything about him, his head, chin, and wrists, was thin and angular. Later when they often waded into the river mud, people said that the master-in-chief always turned his back on the second assistant as they talked in order not to have to see his horrible shins.

14

WHEN THE HEAT tightened its hold and the Ujana e Keqe subsided considerably, work suddenly intensified around the collection of ditches flanking the river. The laborers extended the trenches one by one as far as the bank itself, and then joined them to the river, whose water now began to flow into them. Seen from above, the channels resembled great leeches, sucking the water from the already enfeebled river.

It took less than two days for the appearance of the Ujana e Keqe to change completely. In place of the gentle play of the waters, thick mud spread everywhere, with a few dull glimmers squinting here and there.

Farther downstream the channels led the water back to the river again, but on the site of the bridge everything was disfigured and bedraggled. Dead fish lay scattered in the mud. Turtles and diver-birds gave a final glimmer before perishing. Wandering bards, arriving from nobody knew where, looked glumly at the wretched spectacle of the river and muttered, “What if some naiad or river nymph has died? What will happen then?”

The old raft was moved a short distance downstream, and the hunchbacked ferryman cursed the newcomers all day.

These new arrivals crossed ceaselessly to and fro through the bog with buckets packed with mud, which so dirtied them that they resembled ghosts. Now not only the river but the whole surrounding area became smeared with mud. Its traces extended as far as the main road, or even farther still, as far as the Inn of the Two Roberts,

The lugubrious, unsociable master-in-chief wandered to and fro amid the tumult of the building site. To protect himself from the sun, he had placed on his head not a straw hat, like the rest of the world, but a visor that only shielded his eyes. Sometimes, against the general muddiness, the rays of the evening sun seemed to strike devilish sparks from his reddish poll People no longer said he was mad; now he was the sole sane exception in the crowd of strangers, and the question was whether he would be able to keep this demented throng in harness.

As time passed, the river became an eyesore. It looked like a squashed eel, and you could almost imagine that it would shortly begin to stink. Regardless of all the damage it had caused, people began to feel pity for it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Three Arched Bridge» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Three Arched Bridge» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.