STORMS

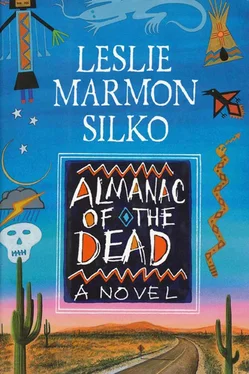

THE ROOM SMELLED faintly of stale cigarettes, but that was all. Seese counted herself lucky the room didn’t reek of urine or sanitary napkins too long in the trash. She rolled a joint and propped herself up in the bed. The wind was whining along the eaves of the stucco bungalow. The gusts splattered sand against the sliding glass doors. Nights like these when she was a girl, she had pulled the covers up to her chin and had gone right to sleep. The sound of the wind had made her feel so snug and safe inside. The sound of rain did the same for other people. Eric had been the only other person who had liked the sound of the wind and sand. Because he had grown up in Lubbock, where, he said, West Texas sandstorms stripped the chrome right off the bumpers of new cars, and windshield glass was so badly sand-pitted it appeared to be fogged.

THE ROOM SMELLED faintly of stale cigarettes, but that was all. Seese counted herself lucky the room didn’t reek of urine or sanitary napkins too long in the trash. She rolled a joint and propped herself up in the bed. The wind was whining along the eaves of the stucco bungalow. The gusts splattered sand against the sliding glass doors. Nights like these when she was a girl, she had pulled the covers up to her chin and had gone right to sleep. The sound of the wind had made her feel so snug and safe inside. The sound of rain did the same for other people. Eric had been the only other person who had liked the sound of the wind and sand. Because he had grown up in Lubbock, where, he said, West Texas sandstorms stripped the chrome right off the bumpers of new cars, and windshield glass was so badly sand-pitted it appeared to be fogged.

Eric had talked about the hailstorms they had out on the West Texas plains. That was what she and Eric had done when David was gone with Beaufrey: they had talked. Because they had both been in love with David, and they liked each other too much for there to be hurt feelings. Eric had had a grand way of setting up a story. He claimed he’d learned it growing up with cowboys, but it turned out his father had had a Ford dealership. The cowboys Eric had listened to were ex-cowboys hired as car salesmen when the ranchers went broke.

The hail, Eric said, was first recorded by the Spaniards with Coronado. Hailstones the size of turkey eggs had dented Spanish helmets and shields. The Spanish horses had bolted and scattered, and a few horses were never recovered. Here of course was where the Plains Indians first got horses. Seese loved to hear Eric go on and on. He knew many wonderful things. He had so much going for himself. It had always been difficult for Seese to imagine Eric with Beaufrey. A few months before it happened, Seese had asked Eric if going home for a visit might cheer him up. Eric had managed to laugh, then shook his head. West Texas was the source of his depression in the first place.

Seese’s mother had worked out an arrangement years ago. She had always known how to spend the salary a lieutenant commander flying combat received. Seese had asked about that too, but her father had laughed. What he liked to do the navy paid him to do. He told Seese she should not be critical of her mother. “She can have whatever she wants. Because she married me, then didn’t get a marriage. That’s grounds for a lawsuit the way I figure it. I’m not the marrying kind.” So her father and mother had gotten even with one another; but Seese did not feel the score had been settled between herself and either of them. Her mother had remarried immediately after the divorce was final. Another military officer, this time air force. He was gone as much as her father had been. He even looked like her father. The last year Seese spent at home, the year she had turned sixteen and they had fought, Seese had screamed at her mother, “What’s the point in being married to him? He’s not even as good as Daddy!” Later Seese thought her mother’s remarriage might not have upset her if her father had lived.

In her grief, Seese had hated that Al was alive when her father was not. She substituted Al for her father in the downed jet fighter whenever she visualized her father’s last mission. One night she and her mother had had a terrible fight over what to cook for Thanksgiving dinner. They had no near relatives. The guests would be couples from the base or friends of Al’s. Seese’s mother had remarked how much Seese’s “late father” had disliked turkey. Now that she was married to a man who ate turkey, that’s what she intended to cook.

Seese had left the house that night, with a suitcase of clothes and $80. She had hitchhiked as far as Santa Barbara the first night. Then, as she had later told Eric, she had got lucky. She ran into Cherie and some other girls. It was a hop, skip, and a jump to Tiny and all the rest. It wasn’t true that she had never seen her mother again. She had stopped in San Antonio once after Al’s transfer.

She had never thought she would be tracking down a psychic. Eric would have laughed if he were alive now. Eric had thought psychics were only for the ignorant or superstitious. Seese had laughed then because that’s what she had thought too. But catastrophe had changed her feelings. Seese turned off the light beside the bed, but she could not sleep. When she closed her eyes, mental images out of the past kept running through her brain like a high-speed movie. She tried to keep the focus only on those scenes or images that felt happy or good, because she had suffered breakdowns in the past. Two of her breakdowns had occurred before she had ever tried cocaine. Still, coke was probably the worst drug to use if your nerves were shaky, unless you really wanted to risk your sanity with LSD.

Seese tried to visualize Monte laughing and playing with other children in a park or school playground. Seese was convinced that a child so beautiful and intelligent as Monte was being reared by people who were loving him as much as they could love any child. Seese had asked the psychiatrist if he agreed that here was the logical way to look at it: her child had been taken because he was valuable and beautiful, and it was not likely any harm would have come to him.

DECOY

SOMETIMES A VOICE inside Seese’s head cried out to Eric, “Why did you kill yourself? Is that what you do to the people who love you?” But she understood exactly why you might do that to the ones you loved. So then gradually, from the grief and the anger Seese had come to feel that she was no more alive than Eric was. That in death she and Eric would always be bound together — sister and brother. There did not seem to be a vocabulary for what they had felt. Or if there had been a vocabulary, she hadn’t understood it.

SOMETIMES A VOICE inside Seese’s head cried out to Eric, “Why did you kill yourself? Is that what you do to the people who love you?” But she understood exactly why you might do that to the ones you loved. So then gradually, from the grief and the anger Seese had come to feel that she was no more alive than Eric was. That in death she and Eric would always be bound together — sister and brother. There did not seem to be a vocabulary for what they had felt. Or if there had been a vocabulary, she hadn’t understood it.

Eric would start talking and mention names of books. The first few times he had done this, Seese had felt a panic — a sudden need for another beer. But later on, Eric told her he admired the people — women especially — who had gone out on their own when they had just finished high school. He had not done that, exactly, but when he had turned fourteen, he had asked the Baptist minister to remove his name from the church roster of baptized Baptists in what was a small town, Lubbock. Seese had been a little stunned. She had never belonged to any church. Her mother had not bothered to have Seese baptized.

Eric had never told Seese the whole story about his years with Beaufrey. Eric said it had been because he had been so young then, and fucked up on drugs to boot. “Those were the years before I finally came out”—Eric had smiled faintly—“before I came out and told them I fell in love with guys, not women. But it was all anticlimactic. My father had identified me years before. I had the big fight with them over my art history major. He called me queer and swish and fairy. ‘Faggot.’ Never just ‘fag.’ ”

David was ashamed for anyone to know. Of course, David had been seeing Seese on the sly for some months before. But David had also started spending afternoons swimming nude with Beaufrey.

Beaufrey was always delighted with the quarrels. Beaufrey was always looking for new players. Eric confessed to Seese he had cried himself to sleep the night Beaufrey and David went driving alone in the Porsche along the coast highway. Later Eric said, he had realized how provincial, how stupidly narrow, he was, despite the years away from Lubbock. Wanting David all for himself was just a stupid version of the Bible Belt bourgeois Eric rejected. Seese could rely on Eric to be her friend and ally. After all, they both loved David, didn’t they?

Читать дальше

THE ROOM SMELLED faintly of stale cigarettes, but that was all. Seese counted herself lucky the room didn’t reek of urine or sanitary napkins too long in the trash. She rolled a joint and propped herself up in the bed. The wind was whining along the eaves of the stucco bungalow. The gusts splattered sand against the sliding glass doors. Nights like these when she was a girl, she had pulled the covers up to her chin and had gone right to sleep. The sound of the wind had made her feel so snug and safe inside. The sound of rain did the same for other people. Eric had been the only other person who had liked the sound of the wind and sand. Because he had grown up in Lubbock, where, he said, West Texas sandstorms stripped the chrome right off the bumpers of new cars, and windshield glass was so badly sand-pitted it appeared to be fogged.

THE ROOM SMELLED faintly of stale cigarettes, but that was all. Seese counted herself lucky the room didn’t reek of urine or sanitary napkins too long in the trash. She rolled a joint and propped herself up in the bed. The wind was whining along the eaves of the stucco bungalow. The gusts splattered sand against the sliding glass doors. Nights like these when she was a girl, she had pulled the covers up to her chin and had gone right to sleep. The sound of the wind had made her feel so snug and safe inside. The sound of rain did the same for other people. Eric had been the only other person who had liked the sound of the wind and sand. Because he had grown up in Lubbock, where, he said, West Texas sandstorms stripped the chrome right off the bumpers of new cars, and windshield glass was so badly sand-pitted it appeared to be fogged.