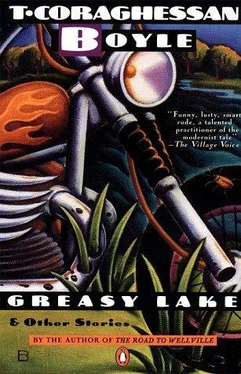

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Stunned, shrunken, humiliated, you stagger back to the dugout in a maelstrom of abuse, paper cups, flying spittle, your life a waste, the game a cheat, and then, crowning irony, that bum Tool, worthless all the way back to his washerwoman grandmother and the drunken muttering whey-faced tribe that gave him suck, stands tall like a giant and sends the first pitch out of the park to tie it. Oh, the pain. Flat feet, fire in your legs, your poor tired old heart skipping a beat in mortification. And now Dupuy, red in the face, shouting: The game could be over but for you, you crazy gimpy old beaner washout! You want to hide in your locker, bury yourself under the shower-room floor, but you have to watch as the next two men reach base and you pray with fervor that they’ll score and put an end to your debasement. But no, Thorkelsson whiffs and the new inning dawns as inevitably as the new minute, the new hour, the new day, endless, implacable, world without end.

But wait, wait: who’s going to pitch? Dorfman’s out, there’s nobody left, the astonishing thirty-second inning is marching across the scoreboard like an invading army, and suddenly Dupuy is standing over you — no, no, he’s down on one knee, begging. Hector, he’s saying, didn’t you use to pitch down in Mexico when you were a kid, didn’t I hear that someplace? Yes, you’re saying, yes, but that was—

And then you’re out on the mound, in command once again, elevated like some half-mad old king in a play, and throwing smoke. The first two batters go down on strikes and the fans are rabid with excitement, Asunción will raise a shrine, Hector Jr. worships you more than all the poets that ever lived, but can it be? You walk the next three and then give up the grand slam to little Tommy Oshimisi! Mother of God, will it never cease? But wait, wait, wait: here comes the bottom of the thirty-second and Brannerman’s wild. He walks a couple, gets a couple out, somebody reaches on an infield single and the bases are loaded for you, Hector Quesadilla, stepping up to the plate now like the Iron Man himself. The wind-up, the delivery, the ball hanging there like a piñata, like a birthday gift, and then the stick flashes in your hands like an archangel’s sword, and the game goes on forever.

Whales Weep

They say the sea is cold, but the sea contains the hottest blood of all….

— D. H. LAWRENCE, “Whales Weep Not”I don’t know what it was exactly — the impulse toward preservation in the face of flux, some natal fascination with girth — who can say? But suddenly, in the winter of my thirty-first year, I was seized with an overmastering desire to seek out the company of whales. That’s right: whales. Flukes and blowholes. Leviathan. Moby Dick.

People talked about the Japanese, the Russians. Factory ships, they said. Dwindling numbers and a depleted breeding stock, whales on the wane. I wanted desperately to see them before they sang their swan song, before they became a mere matter of record, cards in an index, skeletal remains strung out on coat hangers and suspended from the high concave ceilings of the Smithsonian like blueprints of the past. More: I wanted to know them, smell them, touch them. I wanted to mount their slippery backs in the high seas, swim amongst them, come to understand their expansive gestures, sweeping rituals, their great whalish ecstasies and stupendous sorrows.

This cetaceamania was not something that came on gradually, a predilection that developed over a period of months into interest, awareness, and finally absorption — not at all. No: it took me by storm. Of course I’d been at least marginally aware of the plight of whales and dolphins for years, blitzed as I was by pleas from the Sierra Club, the National Wildlife Federation, and the Save the Whales people. I gave up tuna fish. Wrote a letter to my congressman. Still, I’d never actually seen a whale and can’t say that I was any more concerned about cetaceans than I was about the mountain gorilla, inflation, or the chemicals in processed foods. Then I met Harry Macey.

It was at a party, somewhere in the East Fifties. One of those seasonal affairs: Dom Pérignon, cut crystal, three black girls whining over a prerecorded disco track. Furs were in. Jog togs. The hustle. Health. I was with Stephanie King, a fashion model. She was six feet tall, irises like well water, the de rigueur mole at the corner of her mouth. Like most of the haute couture models around town, she’d developed a persona midway between Girl Scout and vampire. I did not find it at all unpalatable.

Stephanie introduced me to a man in beard, blazer, and bifocals. He was rebuking an elderly woman for the silver-fox boa dangling from her neck. “Disgusting,” he snarled, working himself into a froth. “Savage and vestigial. What do you think we’ve developed synthetics for?” His hair was like the hair of Kennedys, boyish, massed over his brow, every strand shouting for attention; his eyes were cold and messianic. He rattled off a list of endangered species, from snail darter to three-toed sloth, his voice sucking mournfully at each syllable as if he were a rabbi uttering the secret names of God. Then he started on whales.

I cleared my throat and held out my hand. “Call me Roger,” I said.

He didn’t even crack a smile. Just widened his sphere of influence to include Stephanie and me. “The blue whale,” he was saying, flicking the ash from his cigarette into the ashtray he held supine in his palm, ‘is a prime example. One hundred feet long, better than a quarter of a million pounds. By far and away the largest creature ever to inhabit the earth. His tongue alone weighs three tons, and his penis, nine and a half feet long, would dwarf a Kodiak bear. And how do we reward this exemplar of evolutionary impetus?” He paused and looked at me like a quiz-show host. Stephanie, who had handed her lynx maxicoat to the hostess when we arrived, bowed twice, muttered something unintelligible, and wandered off with a man in dreadlocks. The old woman was asleep. I shrugged my shoulders.

“We hunt him to the brink of extinction, that’s how. We boil him down and convert him into margarine, pet food, shoe polish, lipstick. ”

This was Harry Macey. He was a marine biologist connected with NYU and, as I thought at the time, something of an ass. But he did have a point. Never mind his bad breath and egomania; his message struck a chord. As he talked on, lecturing now, his voice modulating between anger, conviction, and a sort of evangelical fervor, I began to develop a powerful, visceral sympathy with him. Whales, I thought, sipping at my champagne. Magnificent, irreplaceable creatures, symbols of the wild and all that, brains the size of ottomans, courting, making love, chirping to one another in the fathomless dark — just as they’d been doing for sixty million years. And all this was threatened by the greed of the Japanese and the cynicism of the Russians. Here was something you could throw yourself into, an issue that required no soul-searching, good guys and bad as clearly delineated as rabbits and hyenas.

Macey’s voice lit the deeps, illuminated the ages, fired my enthusiasm. He talked of the subtle intelligence of these peaceful, lumbering mammals, of their courage and loyalty to one another in the face of adversity, of their courtship and foreplay and the monumental suboceanic sex act itself. I drained my glass, shut my eyes, and watched an underwater pas de deux : great shifting bulks pressed to one another like trains in collision, awesome, staggering, drums and bass pounding through the speakers until all I could feel through every cell of my body was that fearful, seismic humping in the depths.

Two weeks later I found myself bobbing about in a rubber raft somewhere off the coast of British Columbia. It was raining. The water temperature was thirty-four degrees. A man unlucky enough to find himself immersed in such water would be dead of exposure inside of five minutes. Or so I was told.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.