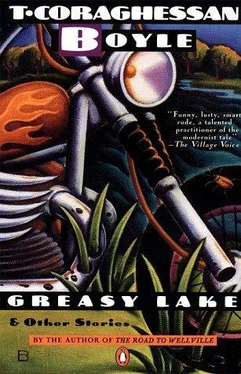

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The old man was wearing a plaid bathrobe and slippers. His frame was big, flesh wasted, his skin the color and texture of beef jerky. He talked for two hours, the strange nasal voice creaking like oars in their locks, rising and falling like the tide. He told us of a sperm whale that had overturned a chase boat in the Sea of Japan, of shipmates towed out of sight and lost in the Antarctic, of a big Swede who lost his leg in a fight with flensing knives. With a crack of his knees he rose up out of the chair and took a harpoon down from the wall, cocked his arm, and told us how he’d stuck a thousand whales, hot blood spurting in his face over the icy spume, how it tasted and how his heart rushed with the chase. “You stick him,” he said, “and it’s like sticking a woman. Better.”

There was a copy of the Norsk Hvalfangst-Tildende on the table. Behind me, mounted on hooks, was a scrimshaw pipe, and beside it a huge blackened sheet of leather, stiff with age. I ran my finger along its abrasive edge, wondering what it was — a bit of fluke, tongue? — and yet somehow, in a dim grope of intuition, knowing.

Eyolf was spinning a yarn about a sperm whale that had surfaced beneath him with an eighteen-foot squid clenched in its jaws when he turned to me. “I think maybe you are wondering what is this thing like a bullfighter’s cape hanging from Eyolf s wall?” I nodded. “A present from the captain of the Freya, nearly forty years back, it was. In token of my take of finback and bowhead over a period of two, three hectic weeks. Hectic, oh yah. Blood up to my knees — hot first, then cold. There was blood in my shoes at night. ”

“The leather, Eyolf,” Harry said. “Tell Roger about it.”

“Oh yah,” he said, looking at me now as if I were made of plastic. “This here is off of the biggest creater on God’s earth. The sulphur-bottom, what you call the blue. I keep it here for vigor and long life.”

The old man gingerly lifted it from the wall and handed it to me. It was the size of a shower curtain, rigid as tree bark. Eyolf was smiling and nodding. “Solid, no?” He stood there, looking down at me, trembling a bit with one of his multiple infirmities.

“So what is it?” I said, beginning to lose patience.

“You don’t know?” He was picking his ear. “This here is his foreskin.”

Out on the street Harry said he had a proposition for me. A colleague of his was manning a whale watch off the Peninsula Valdés on the Patagonian coast. He was studying the right whale on its breeding grounds and needed some high-quality photographs to accompany the text of a book he was planning. Would I take the assignment for a flat fee?

My head throbbed at the thought of it. “Will you come along with me?”

Harry looked surprised. “Me?” Then he laughed. “Hell no, are you kidding? I’ve got classes to teach, I’m sitting on a committee to fund estuarine research, I’m committed for six lectures on the West Coast.”

“I just thought—”

“Look, Roger — whales are fascinating and they’re in a lot of trouble. I’m hoping to do a monograph on the reproductive system of the rorquals, in fact, but I’m no field man. Actually, pelagic mammals are almost as foreign to my specialty area as elephants.”

I was puzzled. “Your specialty area?”

“I study holothurians. My dissertation was on the sea cucumber.” He looked a little abashed. “But I think big.”

The Patagonian coast of Argentina is a desolate, godforsaken place, swept by perpetual winds, parched for want of rain, home to such strange and hardy creatures as the rhea, crested tinamou, and Patagonian fox. Darwin anchored the Beagle here in 1832, rowed ashore and described a dozen new species. Wildlife abounded. The rocks were crowded with birds — kelp and dolphin gulls, cormorants in the thousands, the southern lapwing, red-backed hawk, tawny-throated dotterel. Penguins and sea lions lolled among the massed black boulders and bobbed in the green swells, fish swarmed offshore, and copepods — ten billion for each star in the sky — thickened the Falkland current until it took on the consistency of porridge. Whales gathered for the feast. Rights, finbacks, minkes — Darwin watched them spouting and lobtailing, sounding and surfacing, courting, mating, calving.

Nothing has changed here — but for the fact that there are fewer whales now. The cormorants and penguins and seals are still there, numbers uncountable, still battening on the rich potage that washes the littoral. And still undisturbed by man — with one small exception. The Tsunamis. Shuhei, Grace, and their three daughters. For five months out of the year the Tsunamis occupy the Peninsula Valdés, living in a concrete bunker, eating pots of rice, beans, and fish, battling the wind and the loneliness, watching whales.

Stephanie and I landed with the supply plane, not two hundred feet from the Tsunami bunker. It was August, and the right whales were mating. During the intervening months I’d nursed my split head, drained pitchers of piña coladas, and gone back to the Junior Miss circuit. But I kept in touch with Harry Macey, read ravenously on the subject of whales, joined Greenpeace, and flew to Tokyo for the trial of six members of a cetacean terrorist group accused of harpooning a Japanese industrialist at the Narita airport. I attended lectures, looked at slides, visited Nantucket. At night, after a long day in the studio, I closed my eyes and whales slipped through the Stygian sea of my dreams. There was no denying them.

Grace was waiting for us as the Cessna touched down: hooded sweatshirt, blue jeans, eyes like polished walnut. The girls were there too — Gail, Amy, and Melia — bouncing, craning their necks, rabid with excitement at the prospect of seeing two new faces in the trackless waste. Shuhei was off in the dunes somewhere, in a welter of sonar dishes, listening for whales.

I shook hands with Grace; Stephanie, in a blast of perfume and windswept hair, pecked her cheek. Stephanie was wearing seal-skin boots, her lynx coat, and a “Let Them Live” T-shirt featuring the flukes of a sounding whale. She had called me two days before I was scheduled to leave and said that she needed a vacation. Okay, I told her, glad to have you. She found a battery-operated hair dryer and a pith helmet at the Abercrombie & Fitch closeout sale, a wolf-lined parka at Max Bogen, tents, alcohol stoves, and freeze-dried Stroganoff at Paragon; she mail-ordered a pair of khaki puttees and sheepskin mukluks from L. L. Bean, packed up her spare underwear, eyeshadow, three gothic romances, and six pounds of dried apricots, and here she was, in breezy Patagonia, ready for anything.

“Christ!” I shouted, over the roar of the wind. “Does it always blow like this?” It was howling in off the sea, a steady fifty knots.

Grace was grinning, hood up, hair in her face. With her oblate eyes and round face and the suggestion of the hood, she looked like an Eskimo. “I was just going to say,” she shouted, “this is calm for the Peninsula Valdes.”

That night we sat around the Franklin stove, eating game pie and talking whale. Grace was brisk and efficient, cooking, serving, clearing up, joking, padding round the little room in shorts and white sweat socks. Articulated calves, a gap between the thighs: earth mother, I thought. Shuhei was brooding and hesitant, born in Osaka (Grace was from L.A.). He talked at length about his project, of chance and probability, of graphs, permutations, and species-replacement theory. He was dull. When he attempted a witticism — a play on “flukes,” I think it was — it caught us unaware and he turned red.

Outside the wind shrieked and gibbered. The girls giggled in their bunks. We burned our throats on Shuhei’s sake and watched the flames play over the logs. Stephanie was six feet long, braless and luxuriant. She yawned and stretched. Shuhei was looking at her the way an indigent looks at a veal cutlet.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.