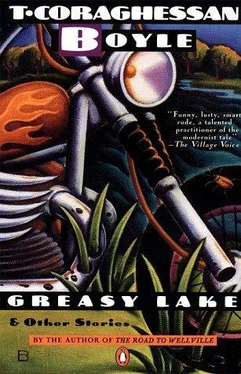

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“First,” Beersley said, clasping his hands behind his back and rocking to and fro on the balls of his feet, “the facts of the case. To begin with, we have a remote, half-beggared duchy under the hand of a despotic prince known for his self-indulgence and the opulence of his court—”

At once the nawab leaped angrily to his feet. “I beg your pardon, sir, but I find this most offensive. If you cannot conduct your investigation in a civil and properly respectful manner, I shall have to ask you to… to—”

“Please, please, please,” Beersley was saying as he motioned the nawab back into his seat, “be patient and you’ll soon see the method in all this. Now, as I was saying: we have a little out-of-the-way state despoiled by generations of self-serving rulers, rulers whose very existence is sufficient to provoke widespread animosity if not enmity among the populace. Next we have the mysterious and unaccountable disappearance of the current nawab’s heirs and heiresses — that is, Gopal, Abha, Shanker, Santha, Bhupinder, Bimal and Manu, Govind, Vallabhbhi Shiva, and now Indira and Sushila — beginning on a moonless night two weeks ago to this day, the initial discovery of such disappearance made by the children’s governess, one Miss Elspeth Compton-Divot. ”

At the mention of the children, the begum, who was seated to my left, began to whimper softly. Miss Compton-Divot boldly held Beersley’s gaze as he named her, the two entrepreneurs — Bagwas and Patel — leaned forward attentively, and Hugh Tureen yawned mightily. As for myself, I began to feel rather sleepy. The room was terrifically hot despite the rain, and the glutinous breeze that wafted up from the punkah bathed me in sweat.

“Thus far,” Beersley continued, “we have a kidnapper whose motives remained obscure — but then the kidnapper turned murderer, and as he felt me close on his trail he attempted murder once again. And let me remind you of the method employed in both cases — a foul and feminine method, I might add-that is, the use of poison. I have here,” he said, producing the nail file, “the weapon used to kill the servant set to watch over the nawab’s flock. It is made of steel and was manufactured in England — in Hertford, to be precise.” At this point, Beersley turned to the governess and addressed her directly. “Is it not true, Miss Compton-Divot, that you were born and raised in Hertfordshire and that but six months ago you arrived in India seeking employment?”

The governess’s face lost its color in that instant. “Yes,” she stammered, “it is true, but—”

“And,” Beersley continued, approaching to within a foot of her chair and holding the nail file out before him as if it were a hot poker, “do you deny that this is your nail file, brought with you from England for some malignant purpose?”

“I don’t!” she shouted in obvious agitation. “Or rather, I do. I mean, yes, it is my nail file, but I lost it — or. . or someone stole it — some weeks ago. Certainly you don’t think that I—?”

“That you are the murderer, Miss Compton-Divot?”

Her face was parchment, her pretty neck and bosom as white as if they’d never seen the light of day.

“No, my dear, not the murderer,” Beersley said, straightening himself and pacing back across the room like a great stalking cat, “but are murderer and kidnapper one and the same? But hold on a minute, let us consider the lines of the greatest poet of them all, one who knew as I do how artifice and deceit seethe through the apparent world and how tough-minded and true one must be to unconfound the illusion from the reality. ‘There was an awful rainbow once in heaven: / We know her woof,’” he intoned, and I realized that something had gone wrong, that his voice had begun to drag and his lids to droop. He fumbled over the next line or two, then paused to collect himself and cast his unsteady gaze out over the room. “‘Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings, / Conquer all mysteries by rule and line, / Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine—’”

Here I cut him off. “Beersley,” I demanded, “get on with it, old boy.” It was the opium. I could see it now. Yes, he’d been up all night with the case and with his pellucid mind, but with his opium bowl too.

He staggered back at the sound of my voice and shook his head as if to clear it, and then, whirling round, he pointed a terrible riveting finger at the game hunter and shrieked: “Here, here is your murderer!”

Tureen, a big florid fellow in puttees and boots, sprang from his chair in a rage. “What? You dare to accuse me, you. . you preposterous little worm?” He would have fallen on Beersley and, I believe, torn him apart, had not the nawab’s Sikhs interceded.

“Yes, Hugh Tureen,” Beersley shouted, a barely suppressed rage shaking his voice in emotional storm, “you who’ve so long fouled yourself with the blood of beasts, you killed for the love of her, for the love of this, this”—and here the word literally burst from his lips like the great Lord’s malediction on Lucifer—“Lamia!”

A cry went round the room. “Oh yes, and she — black heart, foul seductress — led you into her web just as she led you,” he shouted, whirling on the nawab, “Yadavindra Singh. Yes, meeting with you secretly in foul unlawful embrace, professing her love while working in complicity with this man — indicating Bagwas—”and your damned ragged fakir, to undermine your corrupt dynasty, to deprive you of your heirs, poison your wife in her sleep, and succeed to the throne as the fourth begum of Sivani-Hoota!”

Everyone in the room was on his feet. There were twenty disputations, rain crashed at the windows, Tureen raged in the arms of the Sikhs, and the nawab looked as if he were in the throes of an apoplectic fit. Over it all came the voice of Beersley, gone shrill now with excitement. “Whore!” he screamed, descending on the governess. “Conspiring with Bagwas, tempting him with your putrid charms and the lucre the nawab gave out in exchange for your favors. Yes, drugging the children and night nurses with your, quote, hot chocolate!” Beersley swung round again, this time to face the begum, who looked as confused as if she’d awakened to find herself amid the Esquimaux in Alaska. “And you, dear sinned-against lady: your little ones are dead, smothered by Bagwas and his accomplice Patel, sealed in rubber at the plant, and shipped in bulk to Calcutta. Look for them there, so that at least they may have a decent burial.”

I was at Beersley’s side now, trying to fend off the furious rushes of his auditors, but he seemed to have lost control. “Tureen!” he shrieked, “you fool, you jackanapes! You believed in this harlot, this Compton-Divot, this feminine serpent! Believed her when she lay in your disgusting arms and promised you riches when she found her way to the top! Good God!” he cried, breaking past me and rushing again at the governess, who stood shrinking in the corner, “‘Lamia! Begone, foul dream!’‘

It was then that the nawab’s Sikhs turned on my unfortunate companion and pinioned his arms. The nawab, rage trembling through his corpulent body, struck Beersley across the mouth three times in quick succession, and as I threw myself forward to protect him, a pair of six-foot Sikhs drew their daggers to warn me off. The rest happened so quickly I can barely reconstruct it. There was the nawab, foaming with anger, his speech about decency, citizens of the crown, and rural justice, the mention of tar and feathers, the hasty packing of our bags, the unceremonious bum’s rush out the front gate, and then the long, wearying trek in the merciless rain to the Sivani-Hoota station.

Some weeks later, an envelope with the monogram EC-D arrived in the evening mail at my bungalow in Calcutta. Inside I found a rather wounding and triumphant letter from Miss Compton-Divot. Beersley, it seemed, had been wrong on all counts. Even in identifying her with the woman he had once loved, which I believe now lay at the root of his problem in this difficult case. She was in fact the daughter of a governess herself, and had had no connection whatever with Squire Trelawney — whom she knew by reputation in Hertfordshire — or his daughter. As for the case of the missing children, she had been able, with the aid of Mr. Bagwas, to solve it herself. It seemed that practically the only suspicion in which Beersley was confirmed was his mistrust of the sadhu. Miss Compton-Divot had noticed the fellow prowling about the upper rooms in the vicinity of the children’s quarters one night, and had determined to keep a close watch on him. Along with Bagwas, she was able to tail the specious holy man to his quarters in the meanest street of Sivani-Hoota’s slums. There they hid themselves and watched as he transformed himself into a ragged beggar with a crabbed walk who hobbled through the dark streets to his station, among a hundred other beggars, outside the colonnades of the Colonial Office. To their astonishment, they saw that the beggars huddled round him — all of whom had been deprived of the power of speech owing to an operation too gruesome to report here — were in fact the children of the nawab. The beggar master was promptly arrested and the children returned to their parents.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.