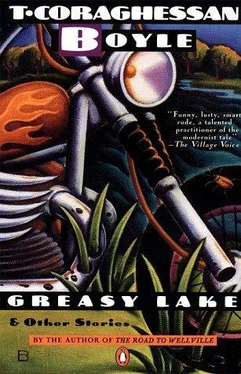

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bayard had smiled. “No problem,” he said. “I’ll pay cash.”

Two months later he and Fran sported matching abdominal scars, wore new flannel shirts and down vests, talked knowledge-ably of seed sets, fertilizer, and weed killer, and resided in the distant rugged reaches of the glorious Treasure State, some four hundred miles from ground zero of the nearest likely site of atomic devastation. The cabin was a good deal smaller than what they were used to, but then, they were used to luxury condominiums, and the cabin sacrificed luxury — comfort, even — for utility. Its exterior was simulated log, designed to make the place look like a trapper’s cabin to the average marauder, but the walls were reinforced with steel plates to a thickness that would withstand bazooka or antitank gun. In the basement, which featured four-foot-thick concrete walls and lead shielding, was the larder. Ranks of hermetically sealed canisters mounted the right-hand wall, each with a reassuring shelf life of ten years or more: bulk grains, wild rice, textured vegetable protein, yogurt powder, matzo meal, hardtack, lentils, bran, Metamucil. Lining the opposite wall, precisely stacked, labeled and alphabetized, were the freeze-dried entrées, from abbacchio alla cacciatora and boeuf bourguignonne to shrimp Creole, turkey Tetrazzini, and ziti alla romana. Bayard took comfort in their very names, as a novice might take comfort in the names of the saints: Just In Case freeze-dried linguine with white clam sauce, tomato crystals from Lazarus Foods, canned truffles from Gourmets for Tomorrow, and Arkson’s own Stash Brand generic foodstuffs, big plain-labeled cans that read CATSUP, SAUERKRAUT, DETERGENT, LARD. In the evenings, when the house was as quiet as the far side of the moon, Bayard would slip down into the shelter, pull the airtight door closed behind him, and spend hours contemplating the breadth, variety, and nutritional range of his cache. Sinking back in a padded armchair, his heartbeat decelerating, breathing slowed to a whisper, he would feel the calm of the womb descend on him. Then he knew the pleasures of the miser, the hoarder, the burrowing squirrel, and he felt as free from care as if he were wafting to and fro in the dark amniotic sea whence he sprang.

Of course, such contentment doesn’t come cheap. The whole package — land, cabin, four-wheel-drive vehicle, arms and munitions, foodstuffs, and silver bars, De Beers diamonds, and cowrie shells for barter — had cost nearly half a million. Arkson, whose corporate diversity put him in a league with Gulf & Western, had been able to provide everything, lock, stock, and barrel, right down to the church-key opener in the kitchen drawer and the reusable toilet paper in the bathroom. There were radiation suits, flannels, and thermal underwear from Arkson Outfitters, and weapons — including a pair of Russian-made AK 47s smuggled out of Afghanistan and an Israeli grenade launcher — from Arkson Munitions. In the driveway, from Arkson Motors, Domestic and Import, was the four-wheel-drive Norwegian-made Olfputt TC 17, which would run on anything handy, from paint thinner to rubbing alcohol, climb the north face of the Eiger in an ice storm, and pull a plow through frame-deep mud. The cabin’s bookshelves were mostly given over to the how-to, survival, and self-help tomes in which Arkson Publications specialized, but there were reprints of selected classics— Journal of the Plague Year, Hiroshima, and Down and Out in London and Paris —as well. Arkson made an itemized list, tallied the whole thing up, and presented the bill to Bayard and Fran in the San Diego office.

Fran was so wrought up at this point she barely gave it a glance. She kept looking over her shoulder at the door as if in expectation of the first frenzied pillagers, and then she would glance down at the open neck of her purse and the.22-caliber Beretta Arkson had just handed her (“My gift to you, Fran,” he’d said; “learn to use it”). Bayard himself was distracted. He tried to look judicious, tried to focus on the sheet of paper before him with the knowing look one puts on for garage mechanics presenting the bill for arcane mechanical procedures and labor at the rate of a hundred and twenty dollars an hour, but he couldn’t. What did it matter? Until he was ensconced in his cabin he was like a crab without its shell. “Seems fair,” he murmured.

Arkson had come round the desk to perch on the near edge and take his hand. “No bargain rate for survival, Bayard,” he said, “no fire sales. If the price seems steep, just think of it this way: Would you put a price on your life? Or the lives of your wife and children?” He’d paused to give Bayard a saintly look, the look of the young Redeemer stepping through the doors of the temple. “Just be thankful that you two had the financial resources — and the foresight — to protect yourself.”

Bayard had looked down at the big veiny tanned hand clutching his own and shaken it mechanically. He felt numb. The past few weeks had been hellish, what with packing up, supervising the movers, and making last-minute trips to the mall for things like thread, Band-Aids, and dental noss — not to mention agonizing over the sale of the house, anticipating Fran’s starts and rushes of panic, and turning in his resignation at the Hooper-Munson Co., where he’d put in fourteen years and worked himself up to Senior Vice President in Charge of Reversing Negative Corporate Image. Without Arkson it would have been impossible. He’d soothed Fran, driven the children to school, called the movers, cleaners, and painters, and then gone to work on Bayard’s assets with the single-mindedness of a general marshaling troops. Arkson Realty had put the condo on the market and found a buyer for the summer place in Big Bear, and Arkson, Arkson, and Arkson, Brokers, had unloaded Bayard’s holdings on the stock exchange with a barely significant loss. When combined with Fran’s inheritance and the money Bayard had put away for the girls’ education, the amount realized would meet Thrive, Inc.’s price and then some. It was all for the best, Arkson kept telling him, all for the best. If Bayard had second thoughts about leaving his job and dropping out of society, he could put them out of his mind: society, as he’d known it, wouldn’t last out the year. And as far as money was concerned, well, they’d be living cheaply from here on out.

“Fran,” Arkson was saying, taking her hand now too and linking the three of them as if he were a revivalist leading them forward to the purifying waters, “Bayard. .” He paused again, overcome with emotion. “Feel lucky.”

Now, two months later, Bayard could stand on the front porch of his cabin, survey the solitary expanse of his property with its budding aspen and cottonwood and glossy conifers, and take Arkson’s parting benediction to heart. He did feel lucky. Oh, perhaps on reflection he could see that Arkson had shaved him on one item or another, and that the doom merchant had kindled a blaze under him and Fran that put them right in the palm of his hand, but Bayard had no regrets. He felt secure, truly secure, for the first time in his adult life, and he bent contentedly to ax or hoe, glad to have escaped the Gomorrah of the city. For her part, Fran seemed to have adjusted well too. The physical environment beyond the walls of her domain had never much interested her, and so it was principally a matter of adjusting to one set of rooms as opposed to another. Most important, though, she seemed more relaxed. In the morning, she would lead the girls through their geography or arithmetic, then read, sew, or nap in the early afternoon. Later she would walk round the yard — something she rarely did in Los Angeles — or work in the flower garden she’d planted outside the front door. At night, there was television, the signals called down to earth from the heavens by means of the satellite dish Arkson had providently included in the package.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.