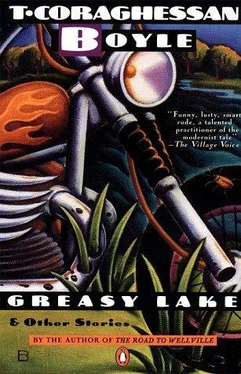

T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «T. Boyle - Greasy Lake and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1986, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greasy Lake and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1986

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Greasy Lake and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

says these masterful stories mark

's development from "a prodigy's audacity to something that packs even more of a wallop: mature artistry." They cover everything, from a terrifying encounter between a bunch of suburban adolescents and a murderous, drug-dealing biker, to a touching though doomed love affair between Eisenhower and Nina Khruschev.

Greasy Lake and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Greasy Lake and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“A concentrate of the venom of the banded krait,” Beersley said, holding a test tube up to the light. It was early, not yet 9:00 n. M., and the room reeked of opium fumes. “Nasty stuff, Planty — works on the central nervous system. I calculate there was enough of it smeared on the nether end of that nail file to dispatch half the unwashables in Delhi and give the nawab’s prize pachyderms the runs for a week.”

I fell into an armchair draped with one of my companion’s Oriental dressing gowns. “Monstrous,” was all I could say.

Beersley’s eyes were lidded with the weight of the opium. His speech was slow; and yet even that powerful soporific couldn’t suppress the excitement in his voice. “Don’t you see, old boy — she’s solved the case for us.”

“Who?”

“The Lamia. It’s a little lesson in appearance and reality. Serpent’s venom indeed, the little vixen.” And then he was quoting: “‘She was a gordian shape of dazzling hue, / Vermilion-spotted, golden, green, and blue. .’ Don’t you see?”

“No, Beersley,” I said, rising to my feet rather angrily and crossing the room to where the clay pipe lay on the dressing table, “no, I’m afraid I don’t.”

“It’s the motive that puzzles me,” he said, musing over the vial in his hand as I snatched the clay pipe from the table and stoutly snapped it in two. He barely noticed. All at once he was holding the nail file up before my face, cradling it carefully in its linen nest. “Do you have any idea where this was manufactured, old boy?”

I’d been about to turn on him and tell him he was off his head, about to curse his narcotizing, his non sequiturs , and the incessant bloody poetry quoting that had me at my wits’ end, but he caught me up short. “What?”

“The nail file, old fellow.”

“Well, er, no. I hadn’t really thought much about it.”

He closed his eyes for a moment, exposing the peculiar deep-violet coloration of his eyelids. “Badham and Son, Manufacturers,” he said in a monotone, as if he were reading an advertisement. “Implements for Manicure and Pedicure, Number 17, Parsonage Lane”—and here he paused to flash open his eyes so that I felt them seize me like a pair of pincers—“Hertford.”

Again I was thunderstruck. “But you don’t mean to say that. . that you suspect—?”

My conjecture was cut short by a sudden but deferential rap at the door. “ Entrez ,” Beersley called, the sneer he cultivated for conducting interrogations or dealing with natives and underlings scalloping his upper lip. The door swung to and a pair of shrunken little houseboys bowed into the room with our breakfast. Beersley, characteristically indifferent to the native distaste for preparing or consuming meat, had ordered kidneys, rashers, eggs, and toast with a pot of tea, jam, and catsup. He moved forward to the table, allowed himself to be seated, and then called rather sharply to the retreating form of the first servant. “You there,” he said, pushing his plate away. The servant wheeled round as if he’d been shot, exchanged a stricken look with his compatriot stationed behind the table, and bowed low. “I want the nawab’s food taster up here tout de suite —within the minute. Understand?”

“What is it, Beersley?” I said, inspecting the plate. “Looks all right to me.” But he would say nothing until the food taster arrived.

From beyond the windows came the fiendish caterwauling and great terrible belly roars of the nawab’s caged tigers as they impatiently awaited their breakfast. I stared down at the bloodied nail file a moment and then at the glistening china plate with its bulbous kidneys, lean red rashers, and golden eggs. When I looked up the food taster was standing in the doorway. He was a young man, worn about the eyes and thin as a beggar from the pressures and uncertainties of his job. He bowed his way nervously into the room and said in a tremulous voice, “You called for me, sahib?”

Beersley merely indicated the plate. “A bit of this kidney here,” he said.

The man edged forward, clumsily hacked off a portion of the suspect kidney, and, closing his eyes, popped it into his mouth, chewed perfunctorily, and swallowed. As his Adam’s apple bobbed on the recoil, he opened his eyes and smiled like a man who’s passed a harrowing ordeal. But then, alarmingly, the corners of his mouth began to drop and his limbs to tremble. Within ten seconds he was clutching his stomach, and within the minute he was stretched out prone on the floor, dead as a pharaoh.

Things had taken a nasty turn. That evening, as Beersley interrogated the kitchen staff with a ferocity and doggedness unusual even for him, I found myself sniffing suspiciously at my bottle of porter,’ and though my stomach protested vigorously, I refused even to glance at the platter of jalebis the nawab’s personal chef had set before me. Beersley was livid. He raged, threatened, cajoled. The two houseboys who had brought the fatal kidney were so shaken that they confessed to all manner of peccancies, including the furtive eating of meat on the part of the one, and an addiction to micturating in the nawab’s soup on the part of the other — and yet clearly they were innocent of any complicity in the matter of the kidney. It was nearly midnight when Beersley dismissed the last of the kitchen servants — the third chutney spicer’s assistant — and turned to me with a face drawn with fatigue. “Planty,” he said, “I shall have your kidnapper for you by tea tomorrow.

He was at it all night. I woke twice — at half past three and close on to six — and saw the light burning in his window across the courtyard. He was indefatigable when he was on the scent, and as I plumped the pillows and drifted off, I knew he would prove true to his word. Unfortunately, in the interval the nawab lost two more children.

The whole house was in a state of agitation the following afternoon when Beersley summoned the nawab and his begum, Messrs. Patel and Bagwas, Hugh Tureen, Miss Compton-Divot, and several other members of the household staff to “an enlightenment session” in the nawab’s library. Miss Compton-Divot, wearing a conventional English gown with bustle, sash, and uplifted bosom, stepped shyly into the room, like a fawn emerging from the bracken to cross the public highway. This was the first glimpse Beersley had allowed himself of her since the night of the entertainment and its chilling aftermath, and I saw him turn sharply away as she entered. Hugh Tureen, the game hunter, strode confidently across the room while Mr. Patel and Mr. Bagwas huddled together in a corner over delicate little demitasses of tea and chatted village gossip. In contrast, the nawab seemed upset, angry even. He marched into the room, a little brown butter-ball of a man, followed at a distance by his wife, and confronted Beersley before the latter could utter a word. “I am at the end of my stamina and patience,” he sputtered. “It’s been nearly a week since you’ve arrived and the criminals are still at it. Last night it was the twins, Indira and er”—here he conferred in a brief whisper with his wife—“Indira and Sushila. Who will it be tonight?”

Outside, the monsoon recommenced with a sudden crashing fall of rain that smeared the windows and darkened the room till it might have been dusk. I listened to it hiss in the gutters like a thousand coiled snakes.

Beersley gazed down on the nawab with a look of such contempt, I almost feared he would kick him aside as one might kick an importunate cur out of the roadway, but instead he merely folded his arms and said, “I can assure you, sir, that the kidnapper is in this very room and shall be brought to justice before the hour is out.”

The ladies gasped, the gentlemen exclaimed: “What?” “Who?” “He can’t be serious?” I found myself swelling with pride. Though the case was as foggy to me as it had been on the night of our arrival, I knew that Beersley, in his brilliant and inimitable way, had solved it. When the hubbub had died down, Beersley requested that the nawab take a seat so that he might begin. I leaned back comfortably in my armchair and awaited the denouement.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Greasy Lake and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.