We went from the soccer game to the ER. They did some scans.

“The brain stem shows a large area of swelling,” a short, olive-skinned doctor said. “We suspect a mass.”

“What?” I said.

“We suspect a mass,” he said.

I could only think of a Mass in church. I could see all of the petitioners, dressed in dark clothes, their pale, drawn faces.

“What?” I said.

•

The end, as it turns out, is lost in details. It’s only a few blocks from the hospital to our flat, but they insisted we take an ambulance anyway.

I’ve got the whole living room set up, with the expensive bed and all the IVs and medicines. The mothers helped with this. I told them I would call and tell them when to come back. I’ve got the hospice nurse coming every day.

“As far as I can tell, we’re three to five days out,” was the way she, the hospice nurse, said it. This I guess she could tell from the bad headaches, the vomiting, the way Haim suddenly can barely move his limbs or his head, the way he can barely swallow. Just like that. Time seems completely beyond you, the traditional divisions (years, months, weeks, days, hours) unmoored from their natural scale inside you, turned into something different, one single period of hourless existence by the side of the hospital bed. It seems like that right up until it doesn’t, right up until someone looks at you and says, “three to five days out.”

“You think you’re such a big perceptive writer-man,” Charlie once screamed at me in an argument when we were young. “But you think a person is really just a body. That if you understand my body, then you understand me, then you love me. As if anyone’s body is anything more than just an evolutionary mistake. As if the body doesn’t persist of its own accord. A person’s not a fucking body. A person’s a person.”

Haim doesn’t sleep much, and when he does, he sweats and twitches. He’s beyond speech now. His first night home he woke up screaming like someone was electrifying him, and trying to clutch at his head. I rushed to add the morphine to his cocktail of Ativan and Zofran like the hospice nurse said I could if he needed it, and he calmed down some. What’s so palliative about this? I thought.

An hour ago one of the nurses from the PICU called and told me that Charlie had just called and left a message with one of the new nurses for her to tell me that she would be landing at Heathrow tomorrow, and would be at the hospital later tomorrow night. The nurse talking to me on the phone said that she was planning on telling Charlie when she got there where I was with Haim, if that was all right with me. The nurse said she’d tried to call Charlie back herself, would’ve just told her where to go now, but they hadn’t been able to find her number. I thanked her and hung up.

Haim has gotten worse all night. I’ve been sitting here watching his oxygen levels tick down steadily. I’ve been on the phone with our hospice nurse, who is across the city dealing with another emergency. I won’t call Charlie. I won’t tell her to hurry. She has finally won my silence. I have finally learned how not to speak.

At some point I must have dozed off because I wake up to a wet gurgling sound. There is a pale liquid, almost like pancake batter, spilling from Haim’s mouth. He is choking on his own vomit, unable to turn his head to the side or sit up. Then I’m standing up and my hands are in his mouth, trying to clear it out, and then I am grabbing him, folding him forward, the vomit spilling onto his lap and there is the sound of his crazed choking for breath, and long tendrils of spit hanging down from his mouth and nose to the mess, and then he is breathing, breathing, collapsing back into a semirecumbent position, and there is the acidic waft of the bile cut with the rotten earthy scent of shit. When I lift up the covers I can see that Haim, in his panic, has soiled himself.

I am standing up, holding him, trying to carry him to the bath, the IV stands tugging along behind us as if being trailed across a wide sea. When I finally get him in the tub and disconnect all the attachments that I need to, I turn on the water and make sure to arrange his head on the lip so that it will be supported. I can see he is having trouble swallowing. He is breathing shallowly, but he will not or cannot open his eyes.

For just a second I straighten up and look back out toward the room, at what Charlie will see tomorrow, if this really is the end. The stained, empty medical bed. The plastic tentacles of the IVs hanging uselessly, disarrayed. The paper wrappers of wound dressing pads scattered on the floor. She will come back, I know, and see me sitting here, waiting for her. She will walk in that door, and see the empty bed, the useless artifacts of so much medicine and look at me in confusion. She will look at me in those few seconds before she understands as if she is asking me a question, as if to say, To what end have I brought this great love into the world? And I will have to look up at her, open my mouth, and answer.

Thank you to the Leah and Robert Hemenway Foundation for Derelict Writers, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the Truman Capote Literary Trust, the John C. Schupes family, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, the University of Iowa, Baylor University, and the Linda Bruckheimer family. Without their support this book would not have been possible.

Thank you to my teachers, especially Jim McPherson, ZZ Packer, Marilynne Robinson, and Allan Gurganus. Thank you to the poet Bill Patterson for putting the right books in my hand. Thank you to David Platt for taking me around the world, to Alexander Chee for showing me how to trace the line of beauty, and to Kevin Brockmeier for sending me into the next dimension. Thank you to Ethan Canin for being my guide and advocate. Thank you to Dr. David Johnson for helping me find my way home in the storm. Thank you above all to Lan Samantha Chang for giving me chance after chance, for being a tireless reader and dedicated teacher, and for giving so much of herself to her students. Thank you, Sam, for being a patient, kind, and honest mentor, and for being my friend.

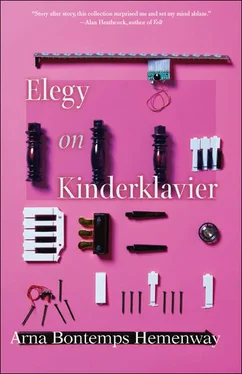

Thank you to everyone at Sarabande Books, especially Sarah Gorham, Kristen Radtke, and Kirby Gann. Thank you to Marshall Rake and Public-Library for their artistic wizardry in helping give this book its cover. Thank you to the editors and magazines who originally published these stories, especially Andrew Feld at The Seattle Review , Ronald Spatz at Alaska Quarterly Review , Alexis Schaitkin at Meridian Literary Review , and Speer Morgan at The Missouri Review . Thank you to Deb West, Jan Zenisek, and Connie Brothers at Iowa for all magic seen and unseen. Thank you to Dianna Vitanza and Greg Garrett at Baylor for your continued support.

Thank you to those friends who helped make this book possible for me, in ways both oblique and direct, especially Alan Heathcock, Rebecca Makkai, Rachel Bailin, Quinn Dreasler, Tawny Alvarez, Jodi Johnson, and Jensen Beach. Thank you to each of my classmates at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for their tolerance, help, patience, and kindness.

I wish there were a full enough way to thank Madhuri Vijay and Tara Atkinson, without whose care, love, and faith I (and these stories) would be lost at sea, but this will have to do: with every day of my grateful life, thank you, thank you, thank you.

Thank you to my mom and dad, for believing I could. Thank you to Bluma Hemenway for calling me to the joy of this world.

And finally, thank you to Marissa Hemenway, the love of my life, to whom I owe every word, heart, and hope in this book.

Читать дальше