Every once in a while another of Charlie’s paintings would sell and I would get an international money order from her with a strange remitter’s address. Because of this, I knew she must be telling her dealer, the one who handled her paintings and finances here in London, where she was staying each time she moved. I knew that if I went down to his gallery in Chelsea, he would probably tell me where she was, and I could do almost anything; I could even go to wherever she happened to be at that moment and confront her, could bring her back, or, at the very least, get a real telephone number with which to speak to her.

But I understood, watching the clips with Haim, strung back to back on an eternal digital loop, that the entire point of this was to avoid speech. That had been her great indictment of me every time we argued, that I made every little thing that should be a four-minute conversation into a forty-minute argument (things which, I knew, in her mind should really even be a forty-second back and forth), that I talked too much, was rude, cut her off in midsentence. “It’s an arrogance,” she said. “You think you know what I’m going to say, but you don’t. You have to think that, because otherwise you’d have no choice but to see that you’re really just afraid that I’m going to say something both true and diminutive about the way you are.” Of course all of this was true. I wanted to keep her bright, quick mind from leaping forward, beyond, with its terrifying ability to articulate with an almost autistic disregard the quintessence of someone as a person. There’re some things, I often thought, that you can’t ever unhear. Most of the time when she said things like this, I told her that I thought it was petty, that I thought we should be talking about more important issues. “What’s a petty problem?” she said. “What else is being married?” And so the video clips were also a rebuke, a punishment. The only way she could live without me talking. The only way she could get me to shut up.

The day after Thanksgiving Haim wanted to watch the videos again. He ended up watching them several times a week, the whole time taking a small stack of secretive notes, as if the clips contained an intricate system of subtle clues with a hidden message only for him. Who were these videos meant for, really? Had Charlie just assumed that I would show them to Haim as they came? I’d told him about where she was after I received each clip, but I hadn’t really explained and he had, self-protectively I think, not asked many questions. I didn’t want him to see that adults could be this way, that they could be so wrong about what love is.

It had been a mercy, anyway, for Charlie that when Haim got sick I didn’t want to talk about it. “Some people talk,” Charlie used to say when we argued, patiently, like she was explaining it to a child. “And some people live.” But during those long months of the holiday, I thought about how it was dying that was really the anti-speech. The great authors in their twilight produce books that grow shorter and shorter, and nobody has much to say about a child with a terminal brain tumor watching the first snow of the year collect on his windowsill. The story refuses to assemble itself. Dying defeats all plot. What would I possibly have had to say to Charlie, even if we did talk?

On the first night of Chanukah I found out one of the nurses on the ward had been giving Charlie information. I had assumed somebody was. I thought about complaining, putting a stop to it. People should have to earn information about the terminally ill, I thought. People should have to come here and stare into the face of it. I didn’t want her to come swooping in if things got bad all of a sudden, as if she’d been here all along. I just wanted her to come home.

The mothers were here by then. I’d set them up in a small flat that they could share near the hospital when they visited. They were both quiet, nervous women, and for most of our marriage they had harbored a congenital dislike of each other, but they had been united in the cause of a sick grandchild and were mostly glad, now that we’d put an ocean between our little family and them, for the chance to see Haim. The nurses and the other families, who, of course, all knew my and Haim’s story, knew about Charlie leaving, were glad to see the mothers around, and gave me big, knowing grins every time they saw me. I couldn’t talk to any of them.

And Haim through all of this? It was hard to know what Haim thought during the holiday and when he thought it. He was quiet most of the time, kept his questions to himself. It helped that we’d started on a new therapy, one of the clinical trials, and it seemed to be working, keeping the size of the tumor stable, though it required a brutal course of infusions, and a host of medicines to counteract its side effects. Right at the beginning, as he was being prepped for one of the scans that would start the trial, he said, “So Mom’s not going to be back for a while, huh?” As if she was late returning from getting takeout. It was so unexpected, I almost laughed.

It has crossed my mind that Charlie’s holiday was not the same thing for Haim as it was for me. Haim understood the sadness of it, for sure, but what is betrayal to a (at the time) seven-year-old? And she did come back, eventually. Do you know that I love you so much that I will show you the world that you cannot see, it might’ve meant to him, and he might be too young to ever understand the sad miscalculation of that, that the world he could not see was the one where he didn’t have an unstable mother who would leave him to die because she could not bear to watch it happen. At the very least by the time the holiday was over, Haim seemed to have aged years, though it was unclear, like everything else, how much of it was due to me, Charlie, the holiday, or his new body.

Charlie came back the day after Christmas, as if that timing meant anything. Haim had gone into respiratory distress, and been rushed down to the PICU. This was the episode where we figured out he would have to sleep with a bi-pap machine from now on. The mothers had been exiled out to the lounge a floor below the PICU, and I was with Haim. One of the nurses told me later that Charlie had just walked into the ward, leading two men who were helping her with a large crate, then dismissed them. The nurse had come in and told her where Haim was, offered to take her down to me in the PICU, but Charlie politely refused. The nurse said Charlie waited in the empty room until she heard Haim was going to be OK, then, before the mothers or I could return, she left. It was two days later, when Haim was back on Pediatric Oncology and doing better, that she came in while he feigned sleep, and I watched her try to reclaim his body from the distortion of flesh.

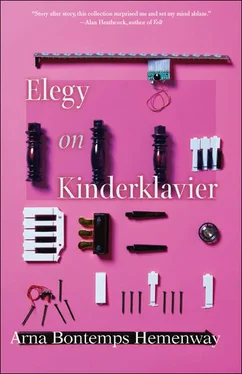

When Haim and I finally came back to the room after he’d been released from the PICU, we found a present. Standing to the side of the space where Haim’s bed was to be rolled was a shiny, red piano-in-miniature. Both Haim and I stared at it. It had a small red bow on its top, the letters kinderklavier spelled out in fancy, golden cursive along the side. It was of a certain size, an in-between scale, not small enough to be a toy, not large enough to be a piano. Haim’s body, bloated, voluminous, could not have even sat at it, let alone played it. There so close to Haim’s pillowy hands, the miniature keys looked impossibly exact. It was too small for Haim to play, too much an imitation of an instrument for us to play for him. It had only three octaves, the tuning nothing if not approximate. What, I thought, could be suitably played on such a ridiculous thing?

It’s now been six months since all of that happened. The story of time, when it is limited, when it is measured in the expansive quality of a child’s experience, is impossible to tell. Time is the story, in a way. The relentless march of it. I never imagined this time I’m living through now during Charlie’s holiday, never thought of it any more than when, in the moments of my worst anger, I tried to imagine what it would be like to divorce her, to greet her on her return, if it ever came, with the papers. But I never imagined what it would be like six months after she came back, never realized that yes you have to live each dramatic moment of your life, but then you have to live the day just after it, and the one after that.

Читать дальше