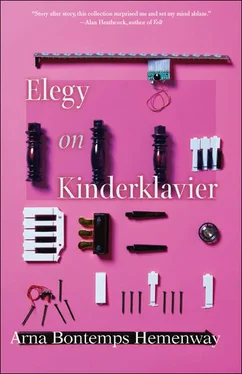

Arna Bontemps Hemenway

Elegy on Kinderklavier

Wild Turkey wakes up. It’s the last day of June, and an early summer thunderhead has marched across the peripheral Kansas plain (the lights of town giving out to the solid pitch of farmland) while Wild Turkey slept. He knew it was coming, the lightning spidering forth behind and then above him last night as he walked, the air promising the rain that is now, as he blinks in the thin blue morning, making the rural highway overpass above his head drone, a room of sound below.

Wild Turkey lifts himself out from the body-shaped concrete depression that nestles just under the eaves of the overpass — that word too big for the little nexus; really it’s just one lonely county road overlapping another. He knew to sleep here last night because of the rain and because he saw the overpass was old enough to have this body-shaped concavity, a “tornado bed” they used to call it, and now he reaches up into the dark of the girder’s angle and feels around until he finds the ancient survival box for those erstwhile endangered motorists: a flashlight that doesn’t work, a rusted weather radio, and — yes — a bottle of water, thick with dust, but Wild Turkey is thirsty and doesn’t care. He stands and stretches on the sloped concrete bank, against the theater of the rain. He was right about the long night-walk out along the country road being good for coming down, the darkness being good for discouraging one of his fits, but wrong about being able to make it to the school before morning.

He makes it to the school now, in the rain, sopping wet. The school is, as it ever was, more or less in the middle of a cornfield, and the thick leaves and stalks cough in the rain as Wild Turkey comes once again upon the old buildings. He rounds the tiny campus in the storm as if he is still in junior high, still traipsing from class to class in the cloying polo and khaki uniform. Now, as then, he does not fail to think of the strangeness of time when he sees the buildings — themselves somehow eternal-feeling, always but only half in ruin. Even in use (back then, as an ad hoc Episcopalian school, and now, apparently repurposed as a childcare center) the moldering white portables and darkly aging main brick building sit in situ, oblivious.

Standing on the concrete path alongside the portables and trying to look into the darkened window of an abandoned room, Wild Turkey has one of his little gyres in time — a brief one, only sending his mind back to those moments when he just an hour ago woke under the little bridge — and he realizes he woke thinking of Mrs. Budnitz, his second-grade teacher, specifically of the rank, slightly fetid scent that would occasionally waft subtly from somewhere inside her gingham dress on a tendril of air in the last weeks of school before summer — though the scent or smell itself wasn’t subtle at all but sharp, rich, pungent, even vaguely sweet, like the smell of human shit anywhere outside a bathroom. Nor was it really a smell so much as an emanation , or at least that’s how it’d seemed to Wild Turkey, sitting on the carpet in the middle of the room, transfixed by this sense delivered to him on the wavering bough of the window fan’s breeze.

They did not have air conditioning installed in their classroom yet, and the heat and consequent sweat, secreted beneath Mrs. Budnitz’s plain, sturdy dresses and folds of fat and thigh, probably amplified the smell. It was only noticeable every ninth or tenth breath and so not really something Wild Turkey ever felt he could speak or complain about. But it was distinctly sexual, or carnal in its fleshy, mildly lurid bodiliness — in its intimate note of vaginal musk, though, of course, this particular understanding would only come later, the experience at the time being importantly a momentary one. The scent refused to linger, and so existed for Wild Turkey mostly in the wince of shame at his own interest, in the same way he sometimes at that age lingered for just a few seconds too long in the school’s bathroom over the shit-stained toilet paper in his hand before flushing it, feeling a rush of something he didn’t understand. It was oddly comforting, in the end.

And why this smell now, or rather, then, upon waking — why does it chase him? Maybe this school harkens his mind back to that other classroom, Wild Turkey thinks. Though really it’s the feeling of it as he drifted on the carpet in Mrs. Budnitz’s classroom during nap time, the confluence of those two sensations — drifting helplessly into a tired, sweaty sleep; drifting helplessly into that intriguing, somewhat disgusting scent. It was a kind of surrender, a voiding of the mind; a reversion to some preinfantile state of abandon. He’s been finding the declensions of that experience in his life ever since, often as he falls asleep, or which he wakes into: the stagnant air of soiled women’s bed linen and spilt chamber pot in the small house in Ramadi; the attenuated scent of the bare bed after he and Merry Darwani had anal sex for the first time; the closeness of the rain-soured, coppery metal of the small bridge’s girding. Wild Turkey is used to his life proceeding this way: this or that detail of his day stepping down out of some first world of previous, essential experience. These sensate allusions are always only whiffs or pale imitations of the original, in the same way that the rainy, pallid light now breaking from the clouds as the morning regains its heat is cousin to the small fist of bright fire over the limbs of the girl in the courtyard in Ramadi, or the rhythmic flash of the tactical grenade’s phosphorous strobe, and all three are mere shavings of the pure white lightning of one of Wild Turkey’s fits.

He turns away from the window. There is nothing to see here. It was stupid to come. He begins the long walk back.

•

Wild Turkey wakes up. He’s eight years old, on his back in the middle of the wheat field that has sprung up by chance in the sprawling park behind his parents’ subdivision. He does not know why he’s on his back, does not remember how he got there. Strangely, however, he does remember what happened just before he woke up, which is that he had his first fit (though he doesn’t know to call it that yet, knows only the image lingering spectacularly in his retinas, in the theater of his mind). He’d been running through the field, feeling the itchy stalks resist his stomping feet, and then he’d been standing in the field, caught up by something in the air, by a small flash in the sky, and then he was looking and looking and seeing only the beauty of the high afternoon sun on the blurry tips of the wheat as it rose and fell on the invisible currents of wind. Like on a seafloor, he thought, just before the brightening in the sky, before it turned in a flash into an overwhelming field of white lightning, so much and so close that he remembers nothing else.

Later, he will not tell the Marine recruiters or doctors about the fits, but will have one anyway on the first night of initiation, before he even gets to boot camp proper. He will be among the guys at the long tables in the gym of the local armory building: the recruits being kept awake all night, forced to keep their hands flat out in front of them, hovering four inches above the tabletop. They are not allowed to move, or to move their hands, or to let their hands touch the tabletop. Then, the lightning.

“Why did you let me stay?” he will ask later, toward the end of actual boot camp, and the instructors will explain (allowing their voices to dilate a little with respect) how he’d looked, sitting there seizing, his hands the only part of him held perfectly still, four inches above the table. Though Wild Turkey will suspect the truthfulness of this, seeing as how he woke up in the wetness of the ditch outside the armory building, his white shirt stained with blood from the tips of the chain-link fence he hopped (he guesses) to escape, the faces of the instructors pale moons in their huddle above him. Eventually he will get medicine for his fits, but the medicine will make him spacey, drowsy — the medicine itself, in effect, simulating the aftereffects of the fits — and so Wild Turkey will be unable to parse his waking. It will never be clear to him whether he is waking from a lacunal fit, the medicine, or a memory, as if all three are essentially the same thing.

Читать дальше