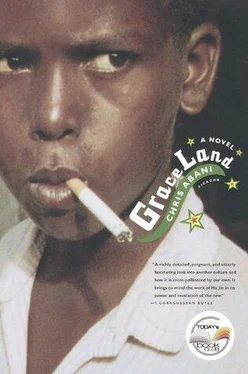

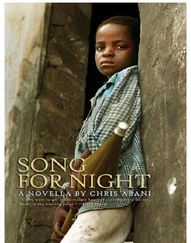

Some distance away from her, a man stood, then sat, then stood again. Now he danced. Stopped. Shook his head and laughed and then hopped around in an odd birdlike gait. He was deep in conversation with some hallucination. It did not seem strange to Elvis that the spirit world became more visible and tangible the nearer one was to starvation. The man laughed, and as his diaphragm shook, Elvis thought he heard the man’s ribs knocking together, producing a sweet, haunting melody like the wooden xylophones of his small-town childhood.

In another spot, a young girl hawked oranges from a tray on her head. She had just got out from school and had barely had time to put down her books before snatching up the tray and heading for the streets. In a poor family everyone had to earn their keep. She sometimes let her male customers feel her firm breasts for a small fee. She marveled at the sweet stickiness she sometimes felt between her legs. She was saving up to go to secondary school.

Elvis traced patterns in the cracked and parched earth beneath his feet. There is a message in it all somewhere, he mused, a point to the chaos. But no matter how hard he tried, the meaning always seemed to be out there somewhere beyond reach, mocking him.

He found a quiet spot that didn’t seem to have a claim staked on it. Curling up, he covered himself with the torn bit of cloth he had been wrapping his father’s corpse in, and settled down to sleep.

Elvis woke up in Bridge City, feeling more than slightly confused. His stomach rumbled noisily but he was too broke to eat. He got up and stretched. He wondered what to do for money, remembering Okon telling him something about selling blood in hospitals. But which hospital? Just then he heard someone call his name. He turned round and, sure enough, there was Okon.

“I was just thinking about you.”

“Den I will indeed live long.”

They both laughed.

“What are you doing here?” Elvis asked.

“I should be asking you. I live here.”

“Since Maroko was demolished?”

“No. For months before den. You?”

“I just got here last night,” Elvis said. “But I’m not ready to talk about it yet.”

Okon nodded sagely: “Words cannot be force. When dey are ready dey will come. Have you eaten yet? No? Come den.”

And over breakfast Elvis probed Okon about what he did. Whether he still sold blood for a living.

Okon laughed. “No. I stop dat long time. For a while we hijacked corpses from roadsides and even homes which we sold for organ transplants.”

Elvis shuddered. Okon noted it.

“I know how you feel,” he said. “It is bad for a man’s soul, waiting at roadside like vulture, for someone to die, so you can steal fresh corpse, but man must survive. When dey start to demand alive people, me I quit. I am not murderer. Hustler? Survivor? Yes. But definitely not a murderer.”

Elvis had stopped eating and had been studying Okon’s face.

“But your face tell me you know about dat type of thing,” Okon continued.

“And now?” Elvis asked.

For the first time he really saw Okon for what he was: a tired man. His eyes were bloodshot and rheumy and fought hard to suppress any glimpse of the soul beneath. His face was weathered dark-brown leather with fine lines all over it.

“I am caretaker.”

“Caretaker?”

“Don’t rush things, my friend — gently, gently. Watch, look, learn. If you like things, den you can join. Until den, just come here and eat. I will square de owner. Okay?” Okon said softly.

Elvis nodded.

“Why are you helping me?” he asked.

“Because nobody help me.”

Elvis looked away, suddenly guilty that he had questioned Okon’s intentions.

“Have you heard anything about the King?” Elvis asked.

“So you never hear?”

“Hear what?”

“De King done die.”

The days passed quickly, and Elvis felt he had always lived in Bridge City. Time lost all meaning in the face of that deprivation. In Bridge City the only thing to look forward to was surviving the evening and making it through the night. Elvis soon got into the swing of things with the help and guidance of Okon. He became a caretaker, guarding the young beggar children while they slept.

Bridge City was a dangerous place, and when darkness fell, it was easy to be very much alone in the crowds that milled everywhere. Hundreds of oil lamps flickered unsteadily on tables, trays, mats spread on the ground and any other surface the hawkers who flocked to Bridge City at night could find to display their wares. Yet even all that light could not penetrate the deeper shadows that hung like presences everywhere.

Young children who had been out all day begging were prime targets for the scavengers spawned by this place. They were beaten, raped, robbed and sometimes killed. So they came up with the idea of “caretakers.” The children paid one set of scavengers to protect them against the others — simple and effective. Just thinking about the degradation made Elvis’s skin crawl. He watched the children huddled on rubber sheeting exposed to the night and the vampire mosquitoes. On rainy nights they slept standing up, swaying with the wind as the rain was blown everywhere, flooding their sleeping places.

The two things Elvis missed most were books and music — not the public embrace of record-store-mounted speakers, but self-chosen music, the sound of an old record scratching the melody from its hard vinyl, or the crackle of a radio fighting static to manifest a song from the mystery of the ether. He often thought about teaching these children to dance. He didn’t expect it to save them, but it would give them something in their lives that they did not have to beg, fight for or steal.

He had come to terms with the King’s death; but he hadn’t come to terms, and probably never would, with the way the King had been deified. He was spoken of with a deeply profound reverence, and the appendage “Blessings be upon his name,” usually reserved for prophets in Islam, was being used whenever his name was invoked. A group of Rastafarians even claimed he was the Emperor Selassie, Christ himself, the Lion of Judah, returned to lead them home.

He hadn’t heard from Redemption for a while and though he asked repeatedly, nobody seemed to have heard from him.

Elvis ran into Madam Caro a week after arriving in Bridge City, where she had already set up a thriving bar. She gave him a bottle of beer on the house and expressed her condolences at his father’s death. When he asked how she knew, she explained that she had run into Comfort a few days after Maroko was razed.

“Did she find his body?” he asked.

Madam Caro nodded.

“But he was not complete. We can only hope he can still find peace on the other side.”

Elvis smiled sadly.

“And Comfort?’

“She done move to Aje. Her shop still dey Balogun side. If you want to visit her, I get de address.”

“Thank you, but no,” he said, shaking his head.

“What of Redemption? Any news?”

She said she hadn’t heard from him but that she would keep her eyes and ears open. She went off to serve another customer. Aside from her limp, she was no worse for wear.

That had been three weeks ago, and hardly a day went by without Elvis wondering if Redemption had survived the Colonel’s men, and if so, where he was. In a few weeks he had lost everyone in Lagos who meant anything to him — his father, the King, Redemption, even Comfort. He was occasionally tempted to ask Madam Caro for Comfort’s address, but always decided against it. Sunday had been the only thing they had in common and now he was dead. Elvis didn’t see the point of contacting her, but it was hard not to give in to the loneliness and feel sorry for himself.

Читать дальше