“Repent, I say. I am a voice crying out in de wilderness. Repent and come unto de Lord before it becomes too late. I saw a vision from de Lord and he did reveal many things to me. Listen — I say, listen,” he said, reinforcing his ranting with loud and generous peals from his bell.

“De Lord says de only road to salvation lies in de Yahweh Adonai Latter Day Prophetic Spiritual and Messianic Church of God and His Blessed Son Jesus of Mount Carmel. Amen. Listen, brethren, I am de representation of dis wonderful Church of God and I call on all who will be saved from damnation to visit us on Sundays near Ojo bus stop and see miracles happen. Witness de power of prayer, de lame shall walk and de blind see. Listen …”

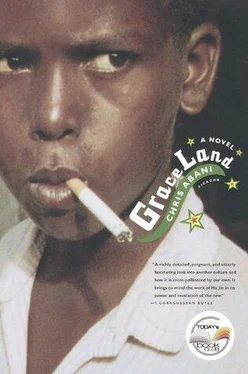

Elvis couldn’t take any more and got off at the Bar Beach stop. It was a nice day, not too hot, with a nice breeze coming off the ocean, and he thought he might make some money off white expatriates and the odd tourist tanning on the beach. They were always surprised and pleased to see an Elvis impersonator here, particularly the Americans, who were often quite generous. He crossed the hot sand of the beach that abutted the Hilton Hotel. As he walked toward the makeshift raffia changing stalls, he noted who was there.

Sprawled on a deck chair was a heavyset man with a gargantuan stomach on which sat an open book. The sun was burning the skin around it and Elvis wondered if the resulting white patch would contain any of the text. A harried-looking woman with red hair and skin reddening to match chased after three excited children, ranging from around five to nine. In her hand was a white smudge of sunscreen, and with her distracted expression, she looked as though she suddenly realized she was holding a bodily secretion. Her husband (if he was her husband) was dozing on another deck chair, which was missing a leg. With every snore it tottered precariously but, defying the laws of physics, remained upright. An elderly couple stood looking out to the horizon, hands cupped against the glare of sun on water as though looking for their lost youth.

Meager pickings, he thought, as he ducked into a stall and shed his street clothes. He slipped into the white shirt and trousers, pulled on the socks and canvas shoes, and jammed the wig down on his head. He couldn’t see himself properly in the small pocket mirror he carried. In Iddoh Park, his usual spot, he had come to rely on the glass shop fronts for his reflection. He hoped he looked fine. He rummaged in his bag for his can of sparkle spray. He couldn’t find it, so he began pulling everything out of the bag, including a journal tied with string. Its leather binding was old and cracked.

Elvis paused for a moment and untied it, flicking quickly through the pages as though in search of a spell to find the lost sparkle spray. His fingers traced the spidery writing. It was his mother’s journal, a collection of cooking and apothecary recipes and some other unrelated bits, like letters and notes about things that seemed as arbitrary as the handwriting: all that he had inherited from her, all that he had to piece her life together. He stared at the page he had opened it to and read the recipe as though it were a fortifying psalm. Closing the journal with a snap, he retied it and returned it to his bag with the other items he’d taken out.

Although he found the sparkle spray, when he tried to use it, he realized he’d run out. He shook the can angrily and depressed the nozzle repeatedly. There was a tired hiss of air, but no sparkle. With a defeated sigh, he turned to the small tin of talcum powder stuck in one of the pockets of his bag. He shook out a handful and applied a thick layer, peering into the mirror. He was dissatisfied; this was not how white people looked. If only he could use makeup, he thought, the things he could do. But makeup was a dangerous option, as he could be mistaken for one of the cross-dressing prostitutes that hung around the beach. They were always hassled by the locals, and often beaten severely. Besides, Oye, his grandmother, used to say in her Scottish accent, “Dinna cry about tha’ things you canna change.” Pulling on his gloves, he grabbed his bag and stepped out.

As he walked over to the foreigners, unable to tell the tourists from the expatriates and embassy staff, he noticed that one of the hotel security guards was spraying water from a hose onto the beach. It seemed odd to Elvis, and the only thing he could think of was that it was meant to cool the sand near the foreigners.

They stopped what they were doing to take in his approach. The gargantuan-bellied man sat up, unread book sliding off his stomach. The sleeping husband woke up with a start, promptly falling to the sand as his deck chair finally gave out. The harried woman stopped chasing the children, who gathered around her legs as the wraith that was Elvis drew closer. Even the old couple had given up the search for their youth to watch him.

“Welcome to Lagos, Nigeria,” Elvis said.

He put his bag down and took several steps away from it, the freshly watered sand crunching under his heels. He cleared his throat, counted off “One, two, three,” then began to sing “Hound Dog” off key. At the same time, he launched into his dance routine.

It built up slowly, one leg sort of snapping at the knee, then the pelvic thrust, the arm dangling at his side becoming animated, forefinger and thumb snapping out the time. With a stumble, because the wet sand, until he adjusted to it, sucked at his feet, he launched into the rest of his routine. It was spellbinding watching him hover over the sand, movements as fluid as a wave, and it was some time before any of the foreigners moved or spoke.

“What d’ya think he’s doing?” the gargantuan-bellied man asked, turning to the father prone in the sand.

“I don’t know.”

“Does he work for the hotel?”

“I don’t know.”

“So what d’ya think he wants?”

“I think he’s doing an Elvis impersonation,” the harried woman said.

“He doesn’t look like any Elvis I know. Besides, ain’t that wig on back to front? Do you think he speaks English?”

“Don’t they all?”

“Hey, son, what do you want?”

Elvis stopped.

“Money,” he replied.

“Like a tip?”

“Anything you want to give.”

“I don’t have any money,” the harried woman said. “But I have some chocolate. Have you had chocolate before?” She reached into her bag and held a Hershey bar out to him.

“No thank you, madam,” Elvis said.

“Hey, Mom, that’s mine!” one of the kids said, grabbing the Hershey bar and running off.

“Bill! Bill!” she called, setting off after him.

“Say, son, are you going to stand there all day?” Gargantuan Belly asked.

“Do you want me to dance some more?”

“No! No!” Gargantuan Belly said.

“I don’t think he’s gonna leave until he gets some money,” Prone Husband chimed in.

“Here,” Gargantuan Belly said, reaching into the pocket of his pants lying in the sand. “Take. Now go, vamoose. Before I set the security guard on you.”

The guard, who had been watching silently, put down the hose when he heard himself referred to. Elvis took the two naira; it hardly seemed worth it. His bus fare cost more.

“No dollars?” he asked.

“Dollars? Beat it, son. Go on, vamoose.”

Elvis watched the guard approaching and, with a sigh, picked up his bag and headed away to the bus stop. Chocolate indeed, he fumed. He got to the bus stop just as a molue was pulling up. He waited for a rather generously proportioned woman to get off. She paused in front of him, taking in his clothes and wig and the talcum powder running in sweaty rivulets down his face.

“Who do dis to you?” she asked.

But before he could answer, she turned and walked away laughing.

Читать дальше