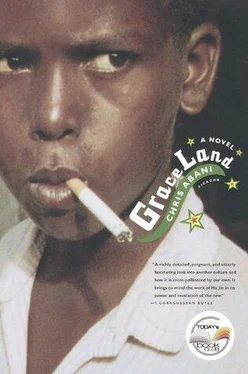

It was summer and schools were on holiday, and Elvis was home, so she summoned him and together they made a pot of too sweet, too milky tea. While she carried the tea, he followed closely, holding the envelopes.

She couldn’t read, but trusted only Elvis to read to her. She figured he was still young enough not to be judgmental or tell too many lies. Oye had never learned how to read or write, and before Elvis was old enough, Beatrice read the letters to Oye, taking her dictated replies down in a beautiful copperplate.

Elvis enjoyed Oye’s trust. It was one of the few times when he felt needed. That sense of importance was nearly threatened when he began to come across the letters written in foreign languages. The most regular came from someone called Gretel and seemed to be in a language that could be German. When he explained the situation to Oye, she laughed heartily at his discomfort and took the letter from him.

“There’s more than one way to skin a cat,” she said, holding the letter between her palms.

“What are you doing?”

“Reading it.”

“How?”

“Ach, laddie, with magic of course,” she said impatiently. “When I hold it like this, I can make out what it’s about.”

“Then why don’t you read all the others like that?” he asked.

“Tha thing with magic, lad, is tha’ it always has consequences.”

She settled back into her wicker chair, Elvis seated at her feet. She sighed and took the letters from him. With practiced casualness, she flicked through them, choosing one. She ripped the envelope and shook out the letter, which she passed to Elvis.

“Read, laddie,” she said slowly.

He took the letter, smiling at the elaborate ritual she had evolved. He wondered what she did on school days; he imagined she prowled the house restlessly until he got back. Clearing his throat, he began.

“Dear Oye …”

Mr. Aggrey took the entire kids’ dance class to the cinema to watch Fred Astaire.

“See how he floats,” he explained. “If you want to be good at dis, watch as many of dese kinds of films as possible.”

“What about Elvis Presley films?” Elvis asked.

Mr. Aggrey smiled. “Elvis Presley too. And Indian films. Watch. Learn. Practice.”

Elvis took the advice to heart. Since the free movies never showed what he wanted to watch, he began to pay to get into the Indian cinema in the next town to watch Elvis Presley, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire and nameless Indian film stars in order to study, close-up and firsthand, the moves of great dancers. He liked the female dancers too, but was afraid to ask Mr. Aggrey if he should learn their moves.

Elvis approached Oye days after the Professor Pele incident and asked her if he could learn the dance moves he had seen performed by the Ajasco dancers. She asked him to find out how much it cost, and if it was not too expensive, she would think about it. Two days later he accosted her as she was sweeping the yard.

“Three naira for each lesson,” Elvis blurted out.

“Watch yourself, boy! You nearly gave me a heart attack.”

“I’m sorry.”

“What is three naira?” she asked.

“The dance lessons I told you about,” he said, launching into an impromptu routine, arms flailing wildly.

“Hey!” Oye interrupted him. “Are you blind? You canna see this broom? Or are you just going tae watch me sweep with my old bones?”

“Sorry, Granny,” he said, taking the broom. “Well?”

“Well, finish sweeping and we’ll talk,” she said, walking off.

Mr. Aggrey was old, with a shiny bald patch and two hedgerows of hair on either side. He was kind despite the walking stick he brought crashing down on knuckles, elbows, knees and anything else with a joint bone. He circled them as they practiced, hawk eyes watching for a missed beat or a hesitation. He was bent a little, and when he hobbled in time to the music, he looked like a large, misshapen turtle.

In addition to the children, Mr. Aggrey also taught adults the waltz and the tango. These were mostly mid-level civil servants preparing for their promotions and the anticipated social evenings that came along with them. Elvis had heard rumors that those selected for promotions were often tested for their ability to handle such social events, so Mr. Aggrey insisted they dress formally for the lessons.

Elvis often stayed back to watch them, hidden by the tall congas standing in the shadows at the back of the open yard where all the lessons were held. They reminded him of the scenes from Chinese films where monks learned martial-art moves in the courtyards of mountain temples. He thought the adults looked funny in their illfitting clothes, which ran the gamut of formal dress from tuxedos and evening gowns through to traditional lace lappas and babanrigas.

Mr. Aggrey worked them hard, tapping out the tempo on the floor with his cane and counting the moves. “Left leg shimmy, right leg shimmy, den turn, left shimmy … No, no, no, Mr. Ibe — left leg. Left leg. Left leg! What are you, Mr. Ibe, an orangutan? Is dis how you will disgrace me at some high-society ball? And you, Mrs. Ebele, dis is not Salome’s Dance of de Seven Veils. If you keep grinding your waist like dat, your partner will have an embarrassment on de dance floor. Okay, from de beginning. Left leg shimmy …”

Elvis watched every day, mentally adding the moves to the ones he already knew. He shuffled along in the shadows, unseen, knowing he would get a beating for not returning home on time after the dance lesson, but not caring.

It was Friday, and as usual, Elvis hid to watch the adult dancers instead of practicing with the other children. Mr. Aggrey waited for the adult dancers to stow their bags before speaking. Elvis observed as several of the dancers noticed twenty rickety wooden crosses leaning on the west wall of the yard. They exclaimed in alarm, and soon a murmur filled the room. None of them wanted to be part of any Satanic rites. Some even backed toward the door, whispering prayers under their breath.

Mr. Aggrey calmed them, explaining that the crosses were there to help them dance. The cross beams would provide support and straighten their backs, providing the stiffer upper-body comportment required in formal dance. With a lot of trepidation, the dancers allowed themselves to be tied to the crosses.

As he watched entranced, Elvis knew what he needed to do to reproduce the Presley hip snap, which he loved dearly, but somehow he couldn’t re-create it, as his movements were more fluid than his hero’s. The first chance he got to practice alone behind the outhouse, he decided he would lash double splints down the side of both legs from the knee down, giving the stiffness needed to get the snap going.

While he finished off the children’s lesson out front, Mr. Aggrey put on some music and left the adults alone to get used to their crucifixion. When he returned, they seemed to be quite happy, whirling around merrily. His breath caught in his throat as he realized that it had worked. They were waltzing, and gracefully. Beautiful black dancers, stapled to wooden crosses that pulled them upright and stiff like marionettes; a forest of Pinocchios, waltzing mug trees, marching like Macbeth’s mythical forest.

AERVA LANATA JUSS.

(Igbo: Okbunzu Nonu)

A straggling, hairy herb found mainly in humid regions, it has elliptic leaves covered with slight hairs and white flowers that grow on the common stalk. The leaves, eaten in soup, are great for sore throats. They induce a heat, exacerbated every time one swallows, which is where the Igbo name comes from. It means literally “to smith in one’s mouth.” The heat caused by the swallowing is likened to that produced by the bellows of the smith.

Читать дальше