Cauliflowers.

Yeah, I just—

Thanks, that’s beaut.

Lester saw the open bag on the table. He looked at Sam’s face and the blood on his shirt.

You off, then?

Yeah, said Sam. I’ve got some business to do.

You’re in trouble.

The stove spat and swallowed. Someone thumped up stairs.

The bookies?

Sam squirmed against the door. Well—

The union, said Dolly.

Ah, the flamin unions, then is it? That bunch of grovellin bullies. By crikey, I can’t … He trailed off and went thoughtful. Need to find a bit of tin to crawl under, eh? Listen, gimme ten minutes. Grab some blankets.

Rose came down the station ramp and saw the Lamb truck going. She waved dutifully and then stood there in the little gust of wind it left in its wake. The old man; that was the old man in the passenger side with his hat pulled down over his eyes. And the cocky, the bird on his shoulder and all. Rose swung her handbag and tried a quick trot but her feet were just too sore from dancing. He’s in the poo, she thought; he just has to be.

Lester drove out north and before either of them spoke the city was behind them, vibrating in the rearview mirrors.

What’s the story? Lester asked.

I gotta keep me lip buttoned, really.

Fair enough.

Sam lit up a smoke. It was something to see, a man with so few fingers rolling and lighting like that.

Your missus clean your face up a bit?

Yeah. Gave me the shock of me life, Sam said with a wetlunged laugh.

What you bring the bird for?

It agrees with everything I say.

What’s she really like, Sam?

The bird or my old lady? Jesus, I dunno. Like she looks. She’s just a rough broad. She used to be … I dunno … softer. We had a lot of bad luck you know. She used to be easier to get along with. She wasn’t such a piss artist in the old days.

Heard from your boy?

How’d you know about that?

Come on, mate, we live between the same walls.

Sam dragged so hard on his smoke, the cab lit up till they could see each other a full few seconds. He’s not so bloody stupid as he seems, Sam thought. He’s the sort of bloke you’d never know what he was capable of. He might come good in a blue, for instance, though he might be a dobber, too. Didn’t he used to be a copper once? A man should never trust an ex-copper.

I haven’t heard from Ted yet. Silly bastard. He’s gonna find his dick in the wringer before long. He’ll end up married to some big bellied girl lookin down the barrels of a shotgun.

Bad way to start a marriage.

Sam snorted. Tell me about it.

Is that your story?

Doesn’t it bloody show?

Lester shrugged politely.

He’s got Sunday School written all over him, thought Sam.

They drove into the dry, capstone country where ragged banksias showed up in the headlamps and groups of roos stood in paddocks, motionless as shire committees.

Where we goin?

A fishin shack. How long will you need?

A week maybe.

Will it blow over or do you have to blow it over?

I reckon I have to do the job meself.

Trouble is, said Sam, thinking as he spoke, that a bit of action costs money. To get things done.

I can’t lend you any, said Lester, the wife wouldn’t have it. He thought: he sounds like a little crim all of a sudden.

Wouldn’t necessarily be a loan. Rent in advance, maybe.

Well, we’re paid up for years already.

Lester turned off towards the coast at a clump of black-boys on a rise. The sky was littered with stars.

You ever thought of buyin it?

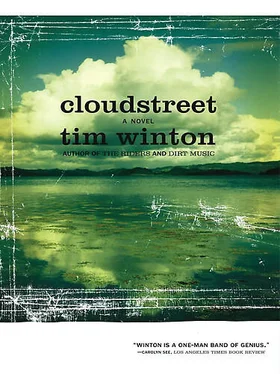

Lester sniffed. Cloudstreet?

It’d be a money spinner.

Hardly made you a rich man, mate, said Lester.

I’ve had a lot of bad luck.

I thought about buyin it once. A long time ago before the old girl moved out the back. But it’s too crowded.

Christ, yelled Sam, it’s hardly deserted. There’s your whole mob and us. And that flatchested Cathlick sheila your missus took in.

No, I mean it feels claustrophobic. Even when it’s empty it feels overcrowded.

Jesus. You believe in luck, Lest? You remember that horse Blackbutt? Luck!

Mm.

It’s like that lighthouse out there. Pointin the finger, like the Hairy Hand of God.

Lester drove silently until he couldn’t bite his tongue any longer. Come clean, Sam, how much do you owe the bookies?

Sam sighed. So the bastard had known all along. Two hundred quid. Some blokes in the union paid it for me.

When was this?

January.

Coo. No wonder they’re a little punchy. Will they just take the money if … you come up with it?

Yeah. I reckon. But I gotta come up with it.

They rolled down between balding dunes where a small river was dammed up behind the beach. A half dozen tin shacks stood concealed from one another by peppermint trees. No lights showed. There were no other vehicles except a rusty old Fordson tractor that looked like it was used to haul boats out of the water. Upturned dinghies stood beneath trees, with the frames of chairs, kerosene tins, broken rope swings from summer. Lester stopped outside a little corrugated place, left the headlights on and got out to work at the padlock with a bunch of keys. Sam stood out of his light, smelling the sea, wondering how it could all go this far.

There’s a coupla crates back in the cab you can bring in, Lester said, getting the door open. A stink of dust and ratshit wafted out.

I didn’t know you had a beach house.

It’s Beryl’s. That flatchested Cathlick sheila you were bein so nice about.

Inside, in the broken beams of light from the Chev, Lester found a lamp, fooled with the wick for a bit, and got it lit. In the sick yellow glow, swimming and bobbing in the uncertain light, the big bed appeared, and the bench, the deal table, the bits and pieces. Sam came in with two boxes.

There’s a fuckin revolver in this crate.

Old army days.

Whatm I sposed to do with that?

You got enough fingers to pull the trigger, haven’t you?

Yeah. But a gun …

I was operatin under the idea that it was a union matter. Keep it here anyway. Shoot rabbits. You’ll need the meat.

You goin?

Lester felt disgust come on him in a rush.

I got a family to get back to. I’ll be back in a week. No one’ll find you out here. Those blokes’ll be back, and I’ll pay em off and come back for you. There wasn’t much camaraderie in his tone, and even he was a little surprised by it. Orright?

Why? Sam said, snaky all of a sudden. What’s in it for you?

What’s in it for me is I don’t have to worry about bruisers hangin round my kids or my house. It buys me some peace of mind.

And a warm feelin, eh, Lester? Sam said bitterly.

Yeah, if you like.

Fair dinkum, said the bird.

Sam swatted it from his shoulder and Lester went out the door to the Chev.

Lester waved and drove off. Sam looked in the boxes. Bread, polony, toilet paper, fruit, vegetables, flour, tea, sugar, a book about John Curtin, a Reader’s Digest and a Smith & Wesson, six shells.

There’s always Russian roulette in the evenings, bird.

Yairs!

Wallpaper

Wallpaper

Red Lamb liked Beryl Lee. She was a hard worker and kind. She treated Fish as though he was special. She’d just arrived one day with a teachest of clothes and no explanation. Apparently the old girl had invited her in, and in the weeks after Hat got married Red was especially glad someone had come along. Her mother had foresight, she knew. Right back then, before Hat fell in love, her mother was recruiting a reinforcement.

Читать дальше

Wallpaper

Wallpaper