The drum stops. Sadie stops. Sweating, breathless. The small gathered crowd ceases clapping and stares. An instant of silence, then Olu: “Go, Sadie!” with all of the might of his baritone voice. The children resume clapping and cheering in Ga, the chubby dancer, “My sees-tah! ” Pictures taken with phones. Fola leaps up from the bench to embrace her as if she has just run a footrace and won. “My God,” she is laughing, clutching Sadie by the forehead. “My daughter’s a dancer, ehn ?” Kissing her braids. Sadie, overcome by belated self-consciousness now that she’s stopped and can feel the warm eyes, lets her mother embrace her, her heart pounding wildly for, among other things, joy.

v

But to see Sadie now in her moment of triumph, enfolded by Fola as she was at the airport (all smiles-through-the-tears, face to breast, and the rest of it), Taiwo feels something rather startlingly like rage. She’s been trying all morning to stick to the script, looking somber, sounding interested, dabbing sweat without complaining, an attempt at being civil that the rest take for sulking, accustomed as they are to her silence, her brooding. This is her preassigned part in the play, as it’s Olu’s to administrate or Kehinde’s to peacekeep or Sadie’s to cry at the drop of a hat or their mother’s to turn a blind eye: Taiwo sulks. They expect it, await it, would miss it if she stopped it. No one worries or asks her what’s wrong, did something happen? That’s just Taiwo, they’ll say with their eyes to each other when they think she can’t see, eyebrows raised, shoulders shrugged.

Such that she, too, believes that she’s always been like this, was a “difficult infant” and will always be difficult— and that , she thinks suddenly, watching Fola and Sadie, if only I were easier, then I’d be hugged, too . Her mother doesn’t hug her, it occurs to her, jarringly. Doesn’t rush to her side at the first sign of need, reserves this privilege for Sadie, who is sweeter and weepy and cute like a doll, like a thing that you hold. So it was yesterday at the dining room table when Fola just stared as she’d started to cry. Had it been Sadie, Taiwo knows, Fola would have embraced her, as now, instead of watching as her daughter walked away.

Rage, out of nowhere. She stares at her mother and feels this rage surging, both startling and embarrassing, that it should come now, with the rest of them laughing, putting grief aside momentarily to celebrate Sadie, small Sadie, sweet Sadie, clean Sadie, pure Sadie, as cute as a baby they can’t help but hug. Out of nowhere, overwhelming, a rage beyond reason. Her body begins trembling, then moving, without bidding: first quivering, then burning, then standing, then walking: without thinking, without speaking, she is walking away. The others don’t notice her go, taking pictures, the children still chattering, older women uninterested. Only Kehinde stands worriedly. “Where you going?” he murmurs. She answers, “To the bathroom,” and he doesn’t pursue.

She hasn’t the foggiest idea where she’s going. Just strides out the entrance to the compound, along the wall, sees the driver by the car, goes the other direction, away from the town, down the dark red dirt road. Rage bids her onward, a visceral seething that quickens her pace and inhibits her thinking so all she can see is her mother hugging Sadie and all she can think is the thought but not me . Rage and self-pity and shame at self-pity. A fire in the legs. Faster, onward, consumed — until, reaching the edge of the village, nearly jogging, she looks up and sees that she’s reached a small clearing. Absent clustered structures obstructing the ocean, the sand beckons, open, like an answer.

• • •

The beach is almost empty, the sun near its height, just the four little boys playing soccer without shoes who smile pleasantly at Taiwo as she appears between palm trees but don’t stop their passing or chitchat in Ga. She pulls off her flip-flops and walks down the sand, which is hard, whitish-gray, piping hot at this hour; feels the rage start to cool with the new, damper air, with the salt taste and sea breeze and sound of the waves; and keeps walking, away from the boys, from their laughter, not thinking, still heaving, now dripping with sweat.

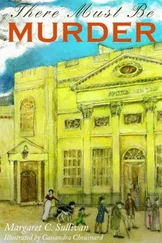

A half mile ahead stands a colonial structure, what looks to have once been some grand beachfront house, complete with terraces and pillars, now abandoned to the sunshine. A few miles beyond another village begins. Somewhere in her mind is the idea of escaping, of making her way to the end of this beach, but the building distracts, looming darkly before her, the sand turning brown in its shadow ahead. It reminds her of that house that she hated, the sullenness, the ghosts of other families, strangers, long-dead Europeans, here plopped on a beach with the boats and the palm trees and few thatch-roofed huts someone’s built in the shade. She stops to consider it: out of place in this picture, as they always felt, an African family in Brookline; as she always felt late at night in her bedroom, the ghosts more at home there than she was. And laughs.

The visual is laughable: this house on a beach in a village in Ghana, some white family home, with its paint stripped away and its eye sockets empty, but here , still assertive, imposing itself. She laughs at the thought of her father, in childhood, a child on this beach looking up at this house, thinking one day he’d have one as big, as assertive, thinking one day he’d conquer some land of his own. Which he did , she thinks, laughing — those acres in Brookline on which stood that equally joyless old home, i.e., “home” as conceived by the same pink-faced British who would have erected this thing on this beach, hulking, rock, a declaration— but without the immovability , the faint air of dominance, the confidence or the permanence. He conquered new land and he founded a house, but his shame was too great and his conquest was sold. Or sold back, very likely, to a sweet pink-faced family, the descendants of Pilgrims, more familiar with dominance. Retrieved from the new boy, returned to the natives, to Cabots or Gardeners, reclaimed from the Sais. Poor little boy, who had walked on this beach, who had dreamed of grand homes and new homelands, she thinks, with his feet cracking open, his soles turning black, never guessing his error (she’d have told him if he’d asked): that he’d never find a home, or a home that would last. That one never feels home who feels shame, never will. She laughs at the thought of that boy on this beach, and laughs harder at the thought of the house that he bought, and laughs hardest at the thought of herself in that house, twelve years old, still a girl, still believing in home.

The usual thing happens:

she laughs until she’s crying with laughter, then crying without it, just crying. Then sitting. Where she is. Drops her bag, just stops walking, has nowhere to go, is a stranger here also. Had she any more energy she’d likely go anyway, start running, waiting (hoping) for some person (man) to follow her — but can’t, is too tired, in her legs, in her body; something seeping out the center, some last stronghold giving in, within. So sits. In the sun, on the sand, sweating, crying. As one sits on beaches. But without the lover’s cardigan.

She fumbles in the bag for her American Spirits, lights one, smokes it quickly; small, jittery motions. She clutches her knees to her chest, to feel closeness, overcome by a grief she can hardly make sense of. The last time she felt this was midnight in Boston, her father slumped over on the couch in his scrubs: that the world was too open, wide open, an ocean, their ship sinking slowly, weighed down by the shame. What she hadn’t known then was that it would be Fola to cut off the ropes, set the lifeboats adrift. Or that it could be Fola. Not a father but a mother. What she hadn’t known then is that mothers betray.

Читать дальше