So it’s come to this, has it? Here barefoot and breathless, alone in his garden, no strength left to shout? Not that it would matter. He is here in the garden; she is there in the bedroom unplugged from the world. The houseboy at home with his sister in Jamestown. The carpenter- cum -gardener- cum -mystic comes tomorrow. Who would hear him shouting? Stray dogs or the beggar. And what would he shout? That it’s finally cracked? No. Somehow he knows that there’s no turning back now.

The last time he felt this was with Kehinde.

A hospital again, 1993.

Late afternoon, early autumn.

The lobby.

Fola down the street in her bustling shop, having moved from the stall at the Brigham last year. A natural entrepreneur, a Nigerian’s Nigerian, she’d started her own business when he was in school, peddling flowers on a corner before obtaining a permit for a stand in the hospital (carnations, baby’s breath). When he’d graduated from medical school and moved them to Boston, she’d started all over from the sidewalk again: by the lunch cart (falafel) in the punishing cold, then the lobby of the Brigham, now the stand-alone shop.

Sadie, almost four, in white tights and pink slippers, doing demi-pliés in her class at Paulette’s.

Olu, high school senior and shoo-in at Yale, attempting doggedly to break his own cross-country record.

Taiwo, thirteen, at the Steinway in the den attempting doggedly to play Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C Sharp while Shoshanna her instructor, a former Israeli soldier, barked instruction over the metronome. “Faster! Da! Fast!”

And Kehinde at the art class Fola insisted he take despite the exorbitant expense at the Museum of Fine Art three short train stops away on the Green Line, up Huntington, where Kweku was to meet him after work.

• • •

Except Kweku never went to work.

He left, calling “Bye!” as he did every morning: in his scrubs and white coat, at a quarter past seven, with Olu waiting for carpool, and the twins eating oatmeal at the breakfast nook table, and Fola braiding Sadie’s hair, and Sadie eating Lucky Charms, and National Public Radio playing loudly as he left. “Bye!” they called back. Three contraltos, one bass, Sadie’s soprano “I love yooou!” just a second delayed, breezing only just barely out the closing front door like a latecomer jumping on an almost-missed train.

He started the Volvo and backed down the driveway. He pushed in the cassette that was waiting in the player. Kind of Blue. He rode slowly down his street listening to Miles. The yellow-orange foliage a feast for the eyes. Pots of gold. In the rearview, a russet brick palace. The grandest thing he’d ever owned, soon to be sold.

• • •

He drove around Jamaica Pond.

He drove under the overpass.

He drove toward their old house on Huntington Ave. He slowed to look out at it. The old house looked back at him. A window cracked, bricks missing, stoop lightly littered. It looked like a face missing teeth and one eye. Mr. Charlie, former owner, would have turned in his grave. Such an attendant to detail. Kweku had liked him so much. American, from the South, with a limp and a drawl. Had lost his wife Pearl over a year before they moved there but still kept her coat on a hook in the hall. He’d given them a 25 percent discount on rent because Fola tended Pearl’s orphaned garden in spring, and because he, Kweku, doled out free medical advice (and free insulin), and because they were “good honest kids.”

Kweku had always greeted him with the Ghanaian Ey Chalé! to which Mr. Charlie always responded, “Tell that story once more ’gain.” (The story: in the forties the officers strewn around Ghana were known as Charlie, all, a suitably generic Caucasian male name. Ghanaian boys would mimic Hey Charlie! in greeting, which in time became Ey Chalé , or so Kweku had heard.) But no matter the man’s insistence, they couldn’t call him by his first name, so well steeped were he and Fola in African gerontocratic mores. Mr. Charlie would hear nothing of sir or Mr. Dyson. (“Mr. Dyson was my daddy, may the bastard rest in peace.”) So “Mr. Charlie.”

Mr. Chalé.

Had driven a bus. Prepared brunch for his sons every Sunday after church, then dispatched them to various DIY projects around the house: rehinging doors, replacing bricks, restoring wood, repainting trim. When he passed (diabetes), the sons inherited the house. The older one said unfortunately the discount was null, effective immediately, given the cost of the funeral next week, to which “Quaker” was invited with “Foola” and the kids. The younger one — the handsome one, his late father’s favorite; a charmer and a drug dealer, unbeknownst to his father — took Kweku to the side at said funeral, a modest funeral, to say in a soft, almost soothing bass murmur, that given their respective lines of work — respectable work, not so different, his and Kweku’s, they both sold “feeling better”—if Kweku could access any meaningful quantities of opiate, a new discount might be arranged.

Now the house was in ruins. A ruin , thought Kweku. Like a temple on a roadside, cracked pillars, heaped trash. Less a lasting commemoration of the efforts of the worshippers than a comment on the uselessness of effort itself. A face missing teeth among similar faces. A falling-apart monument to Charlie’s life’s work: lover, husband, father, bus driver turned homeowner, turned widower, turned statistic (diabetic, black, bested by brunch).

How did we live here? Kweku wondered. All six? And in back, where even sunlight looked dirty somehow? He didn’t know. A car honked. He glanced back. Was blocking traffic. Glanced back at the house, which seemed to say to him: go . He didn’t want to go where he was going, to go forward, but he couldn’t stop moving or stay here or come back. He nodded to the house and pulled out into traffic. In the rearview bricks missing. (He never saw it again.)

• • •

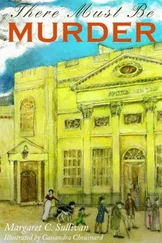

He drove to the Law Offices of Kleinman & Kleinman and parked just a little ways down from the door. It was a free-standing building with a massive front window, the windowsill crowded with overgrown plants. The receptionist, in her sixties, sat facing this window peering idly through the ferns at the road now and then. While still typing. Always typing. She never stopped typing. Her varicosed fingers like robots gone wild.

Kweku had noticed that when he parked outside the window she would peer through the thicket and recognize his car. This gave her just enough lead time to have at the ready that pitying look when he walked through the door. He hated that look. Not the frown-smile of sympathy nor the knit-brow of empathy but the eye-squint of pity. As if by squinting she could make him appear a little less pathetic, soften the edges, blur the details of his face and his fate. Biting her lip as with worry — while still typing. Not that worried.

The pitter-patter rainfall of fingers on keys.

He walked up the sidewalk and entered the building. A bell jingled thinly as he opened the door. “Me again,” he said, as she looked up and squinted.

“You again,” she said with the bitten-lipped smile. “Marty’s waiting to see you.”

Kweku tried to breathe easy. Marty was never in early, liked to make people wait. If he was waiting for Kweku then something was wrong. The cameraman appeared and began setting up his shot. A Well-Respected Doctor receives Horrible News. “All right then.”

“Very well then.”

“So, I’ll just…?”

“Go in, yes.”

“Of course.” Stalling. “Thank you.”

Still typing. “Good luck.”

• • •

Читать дальше