He was starving.

♦

While Connie sat at the kitchen table cradling a mug of tea, Lily lounged up against the Aga, occasionally putting her hand on to the cover of the hot plate to see how many seconds she could hold it there. Connie felt a genuine sense of relief that she wasn’t actually related by blood to this skinny, wasted, round-faced creature. Sara, meanwhile, with admirable diligence, tried to calculate the nature of Connie’s family connection.

“So,” she said, “your father is Lily’s great aunt’s husband’s brother?”

“Yes, he was. But he died.”

“Which makes you something removed.”

Connie smiled at this. She felt like something removed.

Lily, in turn, removed herself from the Aga and sat down next to her. “You drive then?”

She peered at Connie intently, as though this driving characteristic might well prove to be the most interesting thing about her.

“Yes,” Connie nodded.

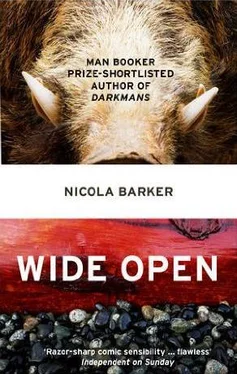

Sara interrupted. “We farm boar, actually,” she said.

“Really? I don’t think I’ve ever seen a boar before. Do they have husks?”

“Tusks.”

Lily snorted.

“The males, yes.” Sara nodded.

“Are they aggressive?”

“Do bears shit in the woods?” Lily revealed her dimples.

“They’re wild,” Sara scowled, “but very…”

“Indigenous,” Lily interjected, “although you wouldn’t think it with all the bother we get.”

Sara cleared her throat. “People can be wary. Other farmers especially. We’ve been keeping boar for a good few years now, but the myth that they escape all the time and wreak havoc…”

“So what!” Lily expostulated. “It’s our land. We can do what the hell we like on it.”

Connie was intrigued. Sara and Lily spoke directly across her, as if she were invisible. Yet she sensed that this was not the sort of conversation they’d usually have. It was as though she acted like some kind of filter. “Could I see them?” she asked.

They both turned to look at her. Sara put down the teapot. “Pardon?”

“The boar. Could I see them?”

“When you’ve finished your tea,” Lily said, “I could take you on a tour of the area. There’s a nature reserve and a beach…”

Connie picked up her mug, took a sip, put it down again. She felt inexplicably genial. “Yes,” she said quietly, “I think I might really enjoy that.”

♦

When Nathan arrived, the gallery was closing. He had at best only fifteen minutes, a guard warned him. Nathan ran up the stairs and into the new Sainsbury Wing. It seemed huge, the ceiling so high. Everything hushed and hollow and reverential. He began walking, quickly, from painting to painting. Ravenous. The gold leaf, the flat faces, the beautiful colour. He gorged on the angels, the devils, the other stuff. He appraised each picture. He paused, he passed on. Is it Christ? He was muttering. But he saw nothing that moved him. Nothing that connected. There was Christ on the cross. The tears, the torment, the suffering. There was Christ down from the cross, surrounded by mourners. A dumb time, a numb time. There was Christ preaching. Open face, open palms. The goldest halo. But nothing.

Is it the artist? He found several other paintings by Antonello. Each so serene and beautiful. One, a self-portrait of the artist himself — with black hair, heavy stubble, blue eyes and a red felt cap. That was all. And another Antonello Christ, but actually on the cross this time, and tiny, and damaged, and nothing spectacular. A picture of Saint Jerome in his study. An exercise in perspective, and wonderful…

He checked his watch. Time up. His heart was pumping.

♦

Sara had disappeared on a mission to borrow some netting from a nearby farm. The pens needed securing. Or so she’d declared. Once she was gone, Lily ransacked the house in search of Luke’s keys but she could not find them. She turned everything upside down, she tipped, she ripped, she swore, she expostulated, but she refused, refused to believe that Sara had hidden them to foil her. She wouldn’t believe it.

Connie went for a wander around the boar pens, supremely oblivious to Lily’s frustrations. There were five different fenced-off sections, each holding eight or ten boar. A single male and his mates. One of the sections contained some smaller boar of varying sizes which she presumed to be adolescents. They were brown and muddy and rather endearing. The big ones, however, were very large, awesome, in a barky, hoary way, and quite intimidating.

Eventually Lily joined her. She seemed disgruntled.

“Did you find what you were looking for?” Connie asked.

“No.” Lily shook her head.

“Shall we go for our walk now?”

“I suppose.”

Lily started off. Connie followed.

“So how are boar different from pigs?”

“The meat’s less fatty.”

“They seem fairly excitable.”

Lily made a little gun out of her right hand. “Click, click, bang! They’re shot at the trough.”

“Really?” Connie felt vaguely stricken at the notion.

“But they’re so fucking powerful that even if you shoot them right in the chest, they run and run, like an engine, like a machine. They’re tough as…uh…” she searched for an appropriate metaphor, “shit,” she said finally.

“They certainly look happy.”

Connie found herself smiling. The boars’ ferocity made her feel buoyant. And Lily’s.

“They are happy. Totally independent. Totally self-sufficient. I mean, we feed them every so often, but not each day because that would make them complacent. They’re wild. Complacency’s like a disease to wild things.”

“You think so?”

“I know so.”

Lily strode on. Connie struggled to keep her pace.

“I was told you kept pigs.”

“We did, years ago, but then we found out about the boar and Dad began interbreeding.”

“With sows you mean?”

“Yep. Same chromosomes. Thirty-six. Strange, huh? It means that you can breed pig and boar without too much difficulty. You get a kind of weird, hairy hybrid…” she shuddered and then continued, “but after a spell he decided that it wasn’t quite right. Boars have a greatness, a purity. And that shouldn’t be tampered with. It should be treasured.”

They had walked well beyond the pens now.

“And they’re much easier to keep than pigs. They even give birth without any fuss. Pigs weren’t as uncomplicated…” Lily scowled at the memory. Connie nodded. “So are we going to the beach?”

Lily ignored her. “And they got terrible sunburn,” she said, “the pigs. Traditional British breeds were very hairy originally but people don’t like pork with hair in the crackling so now they’ve been specially adapted. They have much longer backs, which provides more convenient cuts of meat, but it’s unnatural and causes problems. And their hairlessness means they burn in the sun.”

“I didn’t know that.”

Lily shrugged. “Boar are less work, but you’ve got to be careful to keep them securely.”

“So they do escape sometimes?”

“Once in a blue moon. It’s no big deal.”

Lily stopped walking. “That way is the nature reserve, but if we head straight on we reach the beach.”

“What kind of beach?”

“Shell. It’s OK. There’s a nudist section which is good for a laugh.”

Connie nodded. “That’ll be handy. I haven’t brought a costume.”

Lily stared at her. “You’re planning to go swimming?”

“Sure. Why not?”

Lily merely snorted and strode on.

♦

Sara found the camera in the hide, on the floor, just as Luke had described it to her. It wasn’t a particularly expensive one, but it was his favourite. His best. She picked it up by the strap and then hung it around her neck. He was lucky that it hadn’t been stolen.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу