The prison was like a set of dirty teeth, and the land around it was like a bad mouth, and the sky above it was like the grey face of the person who owned the teeth and the mouth and didn’t care a damn about either of them. Inside, however, people were surprisingly helpful. Connie used her father’s name — like it was a badge, a medal — and that at least seemed to count for something.

Eventually she met a man who claimed some vague — if unspecified — level of significance and so she asked him about Ronny. But he was new, he said, and while he had a file (which he flaunted) he claimed that there were certain things which, in all good conscience, he could not tell her.

She asked if Ronny had shared his cell, if he’d left any belongings behind him, and whether she could — at the very least — take a peek at the cell itself. Yes, the man said, although he wasn’t certain he thought that Ronny may have shared his, cell for a short while, and yes, a meeting with his old cell-mate wasn’t inconceivable — if he proved agreeable — but unfortunately the man in question was elsewhere, had a child sick in hospital so was on a temporary transfer. But he was due back, eventually. Soon even, maybe. Connie scribbled down her forwarding address, in Sheppey, and the unfamiliar digits of her new phone number. She was grabbing at straws. She knew it.

On the understanding that it wouldn’t help her one iota, they took her to the cell. It was bare and smelled of fresh paint. She didn’t feel Ronny there. On her way out they mentioned Nathan. They said, “Ronny’s brother has everything. The books, the clothes, the other stuff. All that was remaining.”

Then finally, when she’d almost given up hope, they threw out a bone. A scrap. A parting gift. “I find your concern strange,” the man said, “given that the dates don’t match up.”

“The dates?” Connie was lost. “Which dates?”

“Ronny was long gone by the time your father visited us.”

“So…” she paused, “you’re suggesting that they never even met?”

“No. I’m suggesting that they didn’t meet here. Perhaps they met after. Or maybe even before.” The man gave her a straight look. And that was that. Connie sat in her car for a long while afterwards. She was foiled. She was blank. She was dead-ended, already. She reached over on to the back seat and picked up Monica’s letters. She looked at them. She felt their weight. She sniffed them. New paint. Floor polish. Then she asked herself a question. Is it Monica I’m really tracking down here or is it Ronny? Because Monica was right there. She was ink and fuss and rage and lust. She was life. And Ronny? Who was he? What did he amount to?

The truth of the matter was that she’d never had much of an interest in the present. It was her chief foible. She despised the present. What she craved now — what she’d always craved — was not the present, not the past, but the absent. Not the possible but the impossible. It verged on the perverse, this craving.

It was almost pathological.

And so, by this token, it was not Monica who fascinated her, but Ronny. It was Ronny. It was not the voice that spoke but the ear receiving. It was Ronny. And it was her father. And it was her own sweet and dumb and stupid self. All absent. All vacant. All gone.

Connie rested her forehead on the steering wheel and she S, howled. Hot tears, dry lips, red cheeks. The business. She allowed herself three whole minutes. That was all. Then she wiped her face with her hands, quite brutally, and started up the engine.

♦

Lily prowled around the green Volvo while Sara fed the boar. She had a bucket of beets which she kept on refilling. They had a ton of them, under tarpaulin. She kept glancing over at Lily.

“If only you could drive,” Lily was griping, “then we could take the car back to the prefabs.”

“But I can’t drive.”

“I know, stupid.”

Sara winced. “You could give me a hand if you felt like it.”

Lily kicked the Volvo’s front tyre.

“No.”

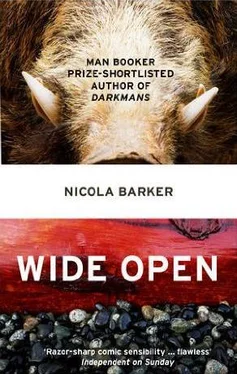

She peered over. The boars were lining up, close to the electric fence. The larger male butted away any female who drew too close. The females — broad hessian parcels with cocked ears — squealed unceremoniously. There’s a whole lot of feeling, Lily thought, in a good squeal.

“I think a fox is around.” Sara spoke.

“Really?” Lily inspected her trainers.

“I found one of my best hens dead this morning.”

“Really?” Lily repeated, smiling to herself.

“Yes.”

Sara pushed some hair behind her ear. Lily sniffed. “You should count yourself lucky that it took only one.”

“Only one, but a good layer.” Sara turned back to the boar. “And this lot have been digging…”

“Where?”

“Towards the back. Part of the fence was down near the gate. I still don’t know how they managed it.”

“Instinct…” Lily squinted, then added, “Car coming.”

Sara put down her bucket and gazed off into the distance. A blue car. She felt an intense surge of delight at the prospect of a distraction. Not for herself, but for Lily. She had her own particular divertions meticulously planned already.

Jim intended to subtly alter the pattern of his life. It was clear to him — and few things were ever clear to him — that Ronny needed significance. Because he barely existed. He wasn’t located. Not anywhere in particular. He was all things to all people. He was malleable. And that was how he had survived, and that was the disease that devoured him.

Jim was willing, if Ronny wanted, to give himself over. To give himself up for Ronny. Because what did he have to lose? It was surely no sacrifice. His name, his gold watch, his shoes, his brother, his home? None of these things amounted to anything. They held no real value. Except to Ronny.

And who could it hurt? Temporarily?

Jim watched Ronny from the edge of the beach. He guarded him. He had eaten no breakfast, as a bolster to Ronny, and he had cut Ronny’s hair with his right hand. He had drawn Ronny’s attention to it. It had taken him hours.

Later, in the mirror, staring at their two reflections, Ronny had said, “You know, Jim, we are very nearly the same person.”

Jim had laughed. Then Ronny pulled open the bathroom cabinet. “If you do things my way,” he said, inspecting the bottles of pills, the packets of tablets, “you won’t need these any more.”

“Fine.” Jim nodded.

“But I mean it.”

“And so do I.”

Although in truth he did not mean it. Not yet.

“Then let’s get rid of them.”

Ronny went and fetched a plastic bag and tipped the bottles and the boxes straight into it. He tied up the handles — using his left hand and his teeth — then took the bag off with him. Later, after no lunch — Ronny’s idea — Jim suggested he go down to the beach to sort out some shells. Ronny was obliging. “Only this time,” Jim said, “you could decorate the wall at the back of the prefab. You could make something permanent.”

Ronny frowned and said he’d give it some thought.

So Jim stood, like a heron, in the reedy fringes of the beach, just watching. Ronny — wearing a baseball cap, his thin face chiselled and clean like a chip of marble — began sorting the shells, then arranging them, then laying them out in some private semblance of order.

He used only his left hand. He seemed cheerful, his equilibrium apparently completely regained. And Jim watched him. He guarded him, like he was a special pedigree poodle, an exotic canary — its wings carefully clipped — or the most lovely and precious little pearl.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу