‘It’s Medve, you moron.’ I wave my hand at him. He doesn’t blink or react. This skinny, flimsy-pyjamaed ginger boy is plainly sleepwalking. I think he believes I’m his brother or someone. I’m not entirely certain but I’m pretty sure I remember him mentioning a single male sibling previously. Slightly older than him. One or two years, maybe?

‘My brother,’ he explains slowly (thereby instantly confirming my suspicions) and speaking like he’s remembering a difficult piece of calculus, or a poem, or a biblical quotation, ‘got bitten by a crocodile in a southern tributary of the great Okovango River…’

I’m about to talk but he interrupts me.

‘On patrol,’ he says suddenly. ‘On the Angolan border. The Caprivi Strip,’ he shudders, ‘in Namibia.’

Then he turns and whistles, over his shoulder, very softly.

‘Was he badly hurt?’

‘Huh?’ he turns back again, plainly irritated.

‘Your brother. Was he hurt? Did it kill him?’

He laughs drily.

‘Why are you laughing?’

‘He was fine. It was a dare . Those were the kinds of things we did back then. You know, just to pass the time when we weren’t murdering the boys from SWAPO or raping their women in the outlying villages…’

He sighs. ‘War can be very boring…’ He pauses, ominously. ‘And that’s always when the truly bad things start to happen…’

His breathing deepens.

‘What were you doing in Namibia?’ I ask gently (if only I’d followed Patch’s reading itinerary — then, at least, all this strategic babble wouldn’t sound like utter Greek to me).

‘I was conscripted. I was fighting …’ he cackles hollowly, then shakes his head. ‘I don’t know what the fuck I was doing… But when they tried to give me a gun…’

He puts out his hands as if to protect himself from something.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘I said, “If you give me a gun I’ll kill you with it.” So they compromised and made me a medic instead.’

He laughs again, but his mouth is turning down at its corners.

‘Did you mean it?’

La Roux scratches his head, confusedly, ‘Mean what …?’ he thinks for a moment. ‘That I’d kill them? Of course not. I could never… That was the whole point , stupid.’

He pauses, keeping his hands in his hair. ‘In the sands of the Namib, the desert children are nannied by dogs. They lick their arses clean when they’ve finished shitting. They keep them spotless. It’s always happened. There’s nothing wrong with it.’

I remain silent.

‘There’s nothing wrong with it ,’ he mutters defensively. ‘I know what you’re thinking. I know. And how after you caught me you could never really bear to look at me again. Not properly. Only sideways. And disapproving. Just like the rest of them. Then the dog gave me ringworm. And you said it was God punishing me for being so completely fucking disgusting .’

He continues to touch his scalp. ‘Do you feel the rings? I feel them.’ He sighs, ‘Spookie would lick them better. We caught lizards in the garden together right up until the day he died. July 15th, 1977. From tick-bite fever.’

We are both silent for a while.

‘I have to get up early in the morning,’ he suddenly informs me. Then he taps his leg, as if calling a dog to heel, and begins walking again, slowly, towards the door. Which is precisely when I’m consumed by a sudden, heart-stopping chill, because that small, dark thing I’d noticed previously is back again, and resolutely trailing in his wake like a clumsy shadow.

I stare a little harder. Then I distinguish this curious creature’s parameters. Not a ghost dog at all, but a huge clump of tangled wool, strung around his right ankle, with Big’s best-beloved crochet odds-and-ends bag bumping and dragging just a short distance behind it.

Sweet Lord above, what a fucking wind- up.

Big returns an hour later. I’m fast asleep in bed by then, but he creeps in on boot-heavy legs to check up on me (I mean, what does he imagine I might be doing?). I open my eyes to see his tiny torso retreating apologetically.

‘Big,’ I whisper.

He peers over his shoulder. ‘Go back to sleep.’

I sit up. ‘Where did you get to?’

‘I just went walking.’

‘Where did you end up?’

‘Salcombe. In a pub.’

Even doze-dazed I’m astonished by this revelation. Big is no barfly (he doesn’t have it in him, either socially or digestively speaking). My slow mind instantly starts churning: are things really much worse between him and Mo than I’d initially imagined?

‘Did you drink anything?’ I ask, secretly moved by his manly bravura.

‘Tomato juice with Worcestershire Sauce .’ He rubs his stomach. ‘And I’m paying for it already, actually.’

I deflate internally. ‘And the route? Did you go the Church-stow — Marlborough way?’ (Okay, so I’m a girl obsessed by orientation. No law against that, is there?)

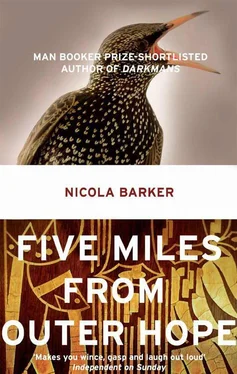

He chuckles. ‘What is this? Twenty questions? I took the small roads. I simply meandered . Uh…’ He counts the villages off on his fingers, ‘Bigbury, Buckland, Outer Hope…’

‘Really?’ I suddenly interrupt him. ‘And how was that?’

He frowns. ‘Pardon me?’

‘Outer Hope. How was it?’

‘Smallish. Couple of pubs. Nothing fancy. In fact…’

‘What?’

He pauses for a moment. ‘I phoned your mother while I was there. From the phone booth. It was…’ There’s a smile in his voice but I can’t really clock his exact expression, ‘a rather bad connection.’

‘Oh.’ I’m suddenly anxious — don’t ask me why — ‘And how was she?’

He shrugs. ‘Full of it. As ever. Told me how Poodle’s been staying with her for a while. Stopped working for Donovan Healy about three weeks ago, and has severed the connection for good, it seems. Mo said she was very obdurate — no, mulish — about the whole thing.’

‘Really?’ I cluck tartly. ‘No surprises there, then.’

He ignores me. ‘She was in hospital in Denver for a few days. Nothing too serious. Just… uh…’ he grapples for the word, ‘something cosmetic .’

His voice sounds disapproving. ‘And she’ll probably be coming home soon, to recuperate properly, but only if we really try and play our cards right. As a family , I mean.’

There’s a warning tone in his voice which I don’t quite appreciate.

‘Okay.’

I lie down again (yes of course I’m absolutely charmed and delighted and ecstatic and everything).

‘Well,’ he says eventually, clearly disturbed by my monosyllabic reaction, ‘I’ll be seeing you in the morning.’

I close my eyes. ‘It is morning, stupid.’

He turns to go. ‘Okay, smart-arse ,’ he mutters, tip-toeing off and closing the door gently behind him, ‘there’s no need to get all flip and sassy with me.’

Five a.m. My fickle eyes (having been as bright as a Chelsea Pensioner’s buttons all the dark night long) would seem to have chosen this hugely inauspicious time to self-seal by way of a glutinous slew of crusty secretions. It’s as if my upper and lower lashes have all been individually crisp-crumbed by the illusory fingers of a phantasmagorical chef, and then slowly and painstakingly golden-battered together. It’s putrid .

I rub away the worst of it as I slam out of the hotel and stagger resolutely downhill to meet with Black Jack for our somewhat untimely fishing assignation.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу