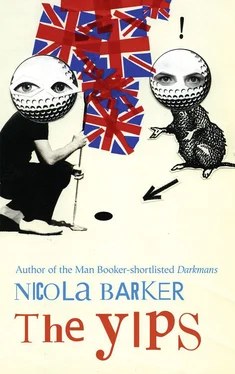

Nicola Barker - The Yips

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicola Barker - The Yips» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Fourth Estate, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Yips

- Автор:

- Издательство:Fourth Estate

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Yips: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Yips»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Yips — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Yips», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I just opened my eyes and took a good look around me.’ Victoria shrugs.

Sheila puts down her coffee, picks up her sandwich and takes another bite.

‘I grew up in Jamaica,’ Victoria expands. ‘When I was sixteen I began working, part-time, in this Anglo-American-owned holiday resort — part of a big franchise. Couldn’t get a job anywhere else … Didn’t take long till I started to notice the glass ceiling for local employees. Everybody in management positions was shipped in from abroad. Same deal with all the items sold in resort stores — even the food served in the restaurants was shipped in from Florida or someplace. It was basically just a new, more subtle kind of colonialism in which our “paradise” culture was superficially celebrated — patronized, boiled down into a series of offensive, easily digestible clichés — and profoundly degraded: local people were banned from the beaches, paid pitiable wages and forced to live in makeshift “service” villages while all the profit they made — and I mean all the profit, every cent — was filtered clean away from the “host” island, straight back to the multinational mothership.’

‘Almost like a modern apartheid,’ Sheila muses, through further mouthfuls of her sandwich.

‘“Almost”?!’ Victoria clucks, outraged. ‘They exploited our resources — because that’s all we were; all our country was — all our country is : a series of “resources” to be pitilessly consumed. They paid no heed to local people, our well-being, our culture or our environment. They’re just cancers, devouring everything that’s good and pumping out filth and disease by way of exchange — poisoning our seas, our rivers, our soils, poisoning our people’s minds, creating a deep sense of disenfranchisement, nurturing feelings of inadequacy and frustration and hopelessness and envy. They’re carcinogenic. They’re the devil incarnate. They sicken me.’

A short silence follows.

‘It must feel good to make a difference,’ Sheila finally volunteers. ‘I always dreamed of making a difference. But it’s so much harder than you think — I mean to break through all the red tape, the petty interests —’

‘It’s not hard,’ Victoria interrupts, flapping her hand, dismissively, ‘it’s only hard if you play by their rules, if you think you can change things, piecemeal, from within. That’s a fool’s approach — pissing in the wind — a criminal waste of valuable energy.’

Victoria takes another bite of her flapjack.

‘In the Church we tend to value the virtue of obedience,’ Sheila explains, ‘to encourage a state of humility …’

‘You think Jesus Christ was obedient, Sister,’ Victoria snorts, ‘or humble? Hah! Shows how much you understand theology!’

Sheila shifts in her seat, uncomfortably. ‘I hear what you’re saying, and I respect your opinion, but I can also see the virtue in compromise. It’s often a harder, more flawed, more frustrating route — I mean there’s this aggressive streak in me which really needs confining …’

‘So don’t confine it!’ Victoria’s exasperated. ‘Act on gut instinct!’

‘That’s what my husband’s always saying’ — Sheila shakes her head — ‘but it’s part of my journey to confine it — a test of my faith.’

‘So nuns can get themselves hitched in this country?’ Victoria exclaims, mugging astonishment.

‘You’ve never felt the urge to improve yourself?’ Sheila asks, scowling.

‘Why tie yourself up in knots?’ Victoria demands, contemptuous. ‘Why over-think everything? That’s definitely a privilege of the West — life’s so easy you need to be inventing problems!’

‘You’re absolutely right, of course,’ Sheila immediately concedes (taking this one square on the chin). She shakes her head, almost forlornly, and smiles. Victoria suddenly — unexpectedly — returns the smile, almost as if she’s seeing Sheila — her essence, her sense of inner conflict, her humanity — for the very first time. The encroaching storm clouds lift from her face. Her eyes glow like two silky dollops of heated molasses. Sheila finds herself reddening slightly under the unexpectedly intense spotlight of this odd woman’s approbation. She takes another bite of her sandwich to disguise her confusion, eventually murmuring, ‘Although if I can offer a small word of warning: I’m not sure if absolute certainty always makes for the greatest autobiography …’

‘ Huh? ’ Victoria’s smile instantly sets. The long shadows return. ‘How so?’

‘Because people need to empathize. I mean if you want this book to be inspirational — a kind of political call to arms — there needs to be the odd chink in the armour …’

Victoria ponders this for a moment.

‘I suppose we might call it the “handrail through the womb” moment,’ Sheila adds, as an afterthought.

‘ Urgh — the handrail!’ Victoria grimaces. ‘Trust me, I had plenty of those in my time. But definitely nothing I feel the need to share. That’s the bit I don’t want to think about. That’s the bit I never want to think about.’

‘And that’s precisely why you’re blocked’ — Sheila shrugs — ‘because the handrail moments provide relief — and meaning — and contrast. They make everything else — the stuff you can control — more vivid, more coherent.’

Victoria pushes her flapjack away (as if the flapjack is the harsh truth she doesn’t want to acknowledge). She remains silent for a while.

‘Perhaps you’re worried that if you commit some of these things — these handrail moments, these perceived “weaknesses” — to paper’ — Sheila pushes her luck still further — ‘that if you face up to them, in print — in public — then not only will you risk showing vulnerability — a dangerous quality in your line of work — but you may even start questioning your whole raison d’être , seeing your protests — your campaigning — in an entirely new light, as part of something more internal, a different kind of struggle …’

‘Nuh- uh. ’ Victoria shakes her head. ‘Vicki Wilson was always bolshy — always stepping outside the boundaries, always slightly off-key — ask anybody. I was born breech, on Halloween. They had to cut me out from my mother’s belly. They heard me screaming before the doctor could finish his incision. Like the wail of a banshee my ma always tells me. Poor old boy was so scared he almost dropped his scalpel!’

‘Is that possible?’ Sheila’s incredulous. ‘I mean for a foetus to actually …?’

‘Nope.’ Victoria shrugs, laughing.

A brief silence follows. Victoria pulls her plate back towards her and prods at her flapjack with her index finger. Sheila finishes off the first half of her sandwich in one large mouthful.

‘I always dreamed of being a writer,’ she starts off, once she’s swallowed.

‘You dreamed of being a lot of things,’ Victoria grumbles, ‘why’d you end up as none of them?’

‘Good point,’ Sheila acquiesces, with a woeful chuckle, wiping her mouth with a paper napkin.

Another short silence and then, ‘I was fifteen,’ Victoria starts off, haltingly, eyes lowered, pushing her flapjack around the plate, ‘just dropped out of school, spending the hours drinking, smoking ganja, dating the son of a local gangsta, not a sensible thought in my head, and my big sister — not me — is working at the local resort, finding lost balls, caddying on their golf course …’ Victoria grimaces. ‘She’s real ambitious, though, funding her own way through university — Applied Sciences; wants to become an engineer. That girl was always clever with her hands, always fixing shit, always making shit … Anyhow, one day she meets this white boy — English boy — pretty handy with a putter — earning a few dollars giving golf lessons at the resort. Beach bum. Long, bleach hair. Musical — keen brass player. Finds out our family is related — my mother’s side — to Francis Johnson, the famous band leader. In fact Aunt Hulda still teaches the keyed bugle in Freetown. He begs an introduction. Starts taking a few lessons. And somewhere along the line we bump into each other — don’t ask me how — I barely remember — and it’s crazy: fireworks! Three months down the line, I’m pregnant. The day I find out, this boy is off on the other side of the island playing in some big-money tournament. The next day he wins the damn thing. The day after that he ups and flies home. No letter, no phone call … And best of all, my big sister leaves with him. They been together ever since.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Yips»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Yips» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Yips» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.