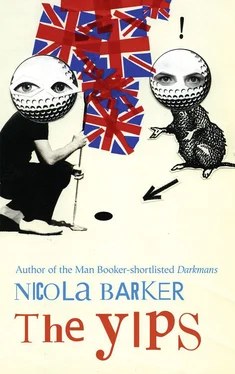

Nicola Barker - The Yips

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nicola Barker - The Yips» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Fourth Estate, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Yips

- Автор:

- Издательство:Fourth Estate

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Yips: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Yips»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Yips — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Yips», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘The woman just looks at me like I’m insane. She says, “How can I be expected to control when he poops? Can you control when you poop?”

‘My God!’ Jen gawps. ‘The cheek of it! I mean I’m in the middle of this romantic …’ Words fail her.

‘Tryst,’ Israel fills in.

‘Precisely, a tryst. I’m right in the middle of my first, romantic tryst with Sinclair and now I have this hare-brained, vindictive cow-bag trying to open a public forum on the intricacies of my bowel movements! I mean she doesn’t even say “business”, she says “poop”! Talk about a passion killer!’

Jen interrupts her narrative for a second and gazes at the boy, concerned. ‘You do know that girls poo, don’t you? Even extraordinarily beautiful ones like moi? ’

‘Sure.’ He nods, wearily. ‘I read Martin Amis’s Rachel Papers in my final year at primary school …’ He pauses. ‘Not as part of the syllabus, obviously.’

‘Good. Because I love dogs,’ Jen continues (not really listening). ‘I’m training to be a vet — well, I’m hoping to become a vet if I can salvage my A-levels. So I’m like: “Duh! I’m training to be a vet! Of course I know that!” Meanwhile the dog’s just twirling away in front of us and now there’s this thin string of dog poo suspended from his rear end with tiny chunks of poo hung on it — strung on it — like poo beads on a poo necklace …’

Israel visibly recoils at the necklace image.

‘Yeah!’ Jen nods, vindicated. ‘I know! Revolting! And naturally the dog is still squatting there, incapacitated, its arse jockeying around in the air, incapable of moving until the poo finally detaches itself.’

‘A critical impasse ,’ Israel primly volunteers.

‘Exactly.’ Jen chuckles, pointing. ‘One of those. So I go to the woman: “What’s wrong with the poor creature? What the hell have you been feeding him?”

‘The owner circles her dog a couple of times, inspecting him closely. “It’s probably just hair,” she says, finally. “He picks it up off the carpet. This happens to all dogs. It’s nothing unusual.”’

‘My grandmother used to weave rag-rugs out of tattered strips of old clothing,’ Israel volunteers; ‘her dog would pilfer the scrap-box and then for literally weeks afterwards his back end would play host to its own, little fireworks party of crap and fabric …’ He smiles fondly at the memory. ‘There was rarely ever a dull moment in Grandmother’s house.’

‘You have so much life experience!’ Jen gushes.

‘Thanks —’ he shrugs — ‘I don’t have my own phone or personal computer, but I keep my eyes peeled and I read a ludicrous amount.’

‘I like you,’ Jen says. ‘Let’s be Besties.’

She offers him her pinkie.

‘I’m not expecting to be in Luton for very long,’ Israel cautions her.

‘Gorgeous, attentive, sincere …’ Jen lists some of his many virtues on her hand, ‘and your vocabulary’s off the scale! Bags you’re on my team for Scrabble!’

The boy inspects her, warily.

‘Gosh! Isn’t it close in here today?’ Jen coyly fans her décolletage. ‘Aren’t you dreadfully itchy in that charming hand-knit?’

‘I hail from the tropics.’ The boy shrugs. ‘In “Yard”’ — he rolls his eyes, sardonically — ‘if you’re not sweating or itching then you’re probably decomposing.’

‘Great use of the vernacular!’ Jen squawks. ‘You’re brilliant! You’re a hoot! Did anyone ever tell you how hilarious you are?’

‘Uh, yes.’

He nods. ‘People tell me that all the time. Even when I’m being perfectly serious. I find it quite trying.’

She gazes at him, bewitched.

‘How old are you?’ she wonders.

‘I’m almost fourteen.’

‘D’you play a musical instrument?’

‘No. You?’

‘Trombone.’

She indicates a dry patch on her upper lip.

‘I’m not musical,’ Israel avows, ‘but one of my great-great-great-uncles on my mother’s side used to play brass with Francis Johnson. There’s a strong, brass tradition in our family. My Great-Aunt Hulda was a famous teacher in Freetown —’

‘Francis who?’ Jen interrupts.

‘He was one of the first really legendary black composers. I’m surprised you haven’t heard of him. That’s actually how my mum ended up meeting my dad. My dad originally played trumpet but he wanted to get into the keyed bugle. He took lessons from my great-aunt …’

‘I’m just crazy for Fela Kuti,’ Jen exclaims, excited. ‘I’m nutty about him — demented. Are you a fan?’

‘Uh … Like I say, I’m not very musical,’ Israel demurs, ‘I’m more of a literary bent.’

‘I love Fela Kuti!’ Jen gushes, undeterred. ‘My brother converted me. You know: the hot brass section, the skin-tight trousers, the pidgin English, the trashy cover-art, the nudity, the stomping, the face-paint. I’m totally into all that radical, seventies, horn-based, semi-psychedelic African shit.’

‘Good for you.’

Israel takes a sip of his Coke.

‘I’m a chameleon,’ Jen confesses, with a dramatic sigh. ‘This …’ — she describes her current, physical incarnation with a cursory swoop of her hand — ‘this isn’t who I am. This is merely a simulacrum, at best.’

‘We don’t have chameleons in Jamaica,’ Israel muses, ‘but we do have something called an Anole — a kind of lizard that changes colour when it’s stressed.’

‘Amazing. Did you ever think about getting contact lenses?’ Jen wonders.

‘I used them for a while,’ Israel confirms, ‘but I was very prone to eye infections.’

‘Like a sticky, white goo all over the eye?’

He winces, remembering.

‘You weren’t cleaning them properly!’ Jen’s ecstatic. ‘I had that problem myself! Now I use disposables — although they’re criminally expensive …’

‘I’m happy enough with my glasses.’ Israel adjusts his glasses, self-consciously.

‘I suppose there’s always corrective eye surgery,’ Jen suggests.

‘I suppose there is,’ he acknowledges.

‘Although sometimes it makes people’s eyes look all wonky.’

‘I’ve heard that.’ He nods.

‘Your dad wears glasses,’ Jen muses. ‘I saw you at reception together. You must’ve inherited the bad gene from his side of the family.’

‘He’s not my father,’ Israel mutters, glancing off sideways.

‘Oh.’

Jen promptly removes Israel’s glasses from his face and commences polishing them on her work blouse.

‘My ma says my real dad had twenty-twenty vision.’ Israel squints at her across the table. ‘She says he needed it for his work: he was a professional arsehole.’

‘I hear there’s great money in that,’ Jen wisecracks.

‘I hate him.’ Israel scowls.

‘Why not divorce him, then?’ Jen suggests, blithely.

‘He’s dead.’ Israel’s still scowling.

‘Doesn’t make any difference. You can always divorce his corpse.’

‘Divorce a parent?’ Israel’s intrigued by the notion.

‘Kids do it all the time nowadays. It’s totally the rage.’

Israel continues to ponder this concept.

‘We should research it on the net together after my shift,’ Jen suggests. ‘I have my own duplicate key to the office …’

She pulls a long, silver chain into view from under her blouse, on the end of which are two keys, a USB stick and a bottle-opener.

‘Won’t you need to get permission?’ Israel asks, concerned.

‘Hell no,’ Jen snorts, ‘I’m a law unto myself. I pop in there all the time to Google information about the guests.’

‘Did you Google information on us?’ Israel wonders, intrigued.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Yips»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Yips» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Yips» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.