That night I stay with Kurt at his house, and I actually call Elsie to tell her that I won’t be coming back until morning. Her voice is careful, perhaps a little sad, but mostly she sounds relieved.

“Good night, dear,” she says.

There are other things that she could say to me, things I will never hear. I doubt that many mothers say these things to their daughters. Maybe it would be like telling your daughter the truth about the pain of childbirth. They try to protect us, even when we’re middle-aged. So I must supply the words for myself:

Life will break you. Nobody can protect you from that, and living alone won’t either, for solitude will also break you with its yearning. You have to love. You have to feel. It is the reason you are here on earth. You are here to risk your heart. You are here to be swallowed up. And when it happens that you are broken, or betrayed, or left, or hurt, or death brushes near, let yourself sit by an apple tree and listen to the apples falling all around you in heaps, wasting their sweetness. Tell yourself that you tasted as many as you could.

I work part of the next afternoon and am driving home early, having sold an Aesthetic Movement rosewood cabinet with lovely Japanese lacquer panels. The piece sat for two years in our shop and Elsie implied several times that it was a mistaken auction purchase on my part and would have to be priced too high to sell to any but the leaf peepers, who would need to hire a delivery service. So I’m happy to sell it—with a cash down payment, no less. I am carrying nearly sixteen thousand dollars in hundred-dollar bills and I am planning how Elsie and I might use this piece of luck. The Eykes’ church sign tells me today that God Saves, but I am going to do something less predictable and safe, later. Right now I’ve decided that this is the day I will visit my sister’s grave. This is a thing I do every fall just about this time. It is sort of like putting her to bed for the winter. I’ll rake away the leaves to find her grave is littered with twigs or ribbons or bits broken off Styrofoam crosses and summer flower arrangements blown over from other graves. I have brought a plastic trash bag and a short clawlike trowel that clanks in the backseat as I turn down the bumpy cemetery road.

Our child cemetery was established during the flu epidemic of 1918, when Stiles and Stokes suffered a grievous number of losses. Even on the brightest days, the air seems a little darker here. The stone lambs that were popular in the early part of the twentieth century are now weathered into soft lumps. There is a headstone that reads “What wild hopes lie here,” and one grave with a small statue of a dog curled at the bottom, as at the foot of that child’s bed. There are cherubs of gentle marble and quiet little markers engraved with the outlines of small hands. Six great maples shed pink light and I’m caught up in their cold glow. The pines planted as seedlings here and there are now black-green and tall. I park beneath a group of three that sigh and mumble as I pass among them. My sister’s stone marker is very distinctive. It’s a carved angel that our mother bought from a church about to be demolished and had engraved with the date and name. Perhaps because the angel was not meant as a memorial in the first place, there is something stealthily alive about her—wings that flare instead of droop, an alert and outwardly directed expression, a hand clutched to her breast not as a gesture of reverence or sorrow, but, I think, breathless delight.

As I am raking away the papery orange and yellow leaves, I turn up a tooth, sharp and vulpine; it gleams ivory white when I polish it on my sweater. I think of Kendra—the tooth would have made a nice earring and she would have worn it with style. I head for the part of the cemetery where she is buried. Kendra’s stone is a white marble sculpture. I’ve never seen it, and when I do I catch my breath. Kurt has made for her the simplest emotional form, a concave circle of Carrara white, both perfect and shadowed. He has never made anything that really moved me before, and I stand there with nothing to say or think at all. After a while, I set the tooth on the stone and walk back to my sister’s place.

The scent of warmed earth, the mold of dead leaves, the angle of sun on my shoulders suddenly floods me with a sharp happiness and I look up to see that the ravens are crossing and circling. Silent, they pass beyond a fringe of pines. When I was small, I imagined that my sister and I would meet after death in the form of birds. I turn back to the earth and keep scratching at the ground, throwing the faded petals of plastic flowers and shatters of plastic into my trash bag. It is a long time before I finish.

On the way back to my car, I pass the space in the pines that gives out on a cliff. There must be an air bank rising and falling because the ravens are playing there. I watch as they throw themselves off a branch into the invisible stream. Over and over, they tumble into the air and fly upside down. They twist themselves upright and soar off, sink, then shoot up again over the lip of rock. Say they have eaten and are made of the insects and creatures that have lived off the dead in the raven’s graveyard—then aren’t they the spirits of the people, the children, the girls who sacrificed themselves, buried here? And isn’t their delight a form of the consciousness we share above and below the ground and in between, where I stand, right here? As I think this, one raven veers toward me, zipping straight at my face, but I do not flinch as its wings brush through my hair. I call out my sister’s name in the wildness of the moment. Then I turn and watch the raven swerve rapidly over the tops of the pines, until she plummets down the cliff again, laughs, and disappears.

What happened to the girl in the beginning of “The Shawl” is based on the experience of an elderly man who told this to Tobasonakwut. I thank him for trusting me with the story. There are other very similar folk tales; one appears in Willa Cather’s My Ántonia . So I can only conclude that all stories exist in continuum and that this actually happened. Yet I also think that the story runs counter to real facts about the shyness and politic avoidance that wolves show to humans. I’ve tried to stay true to both. As in all of my books, no sacred knowledge is revealed. I check carefully to make certain everything I use is written down already. Thomas Vennum’s The Ojibwe Dance Drum: Its History and Construction was particularly helpful to me. I want to thank my editor, Terry Karten, for her clear eye; Trent Duffy, for his close work; and Gail Caldwell, for deepening my vision of this book.

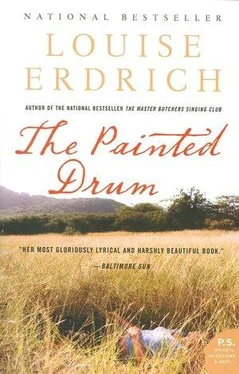

Louise Erdrich is the author of eleven novels as well as volumes of poetry, children’s books, and a memoir of early motherhood. Her novel Love Medicine won the National Book Critics Circle Award. The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse was a finalist for the National Book Award. She lives in Minnesota with her daughters and is the owner of Birchbark Books, a small independent bookstore.

Don’t miss the next book by your favorite author. Sign up now for AuthorTracker by visiting www.AuthorTracker.com.