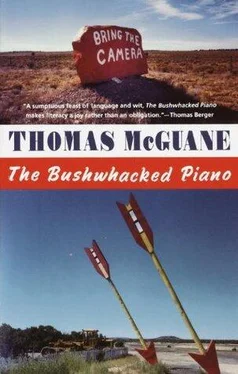

Thomas McGuane - The Bushwacked Piano

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Thomas McGuane - The Bushwacked Piano» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Bushwacked Piano

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Bushwacked Piano: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Bushwacked Piano»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Bushwacked Piano — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Bushwacked Piano», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The homecoming itself was awash in vague remembered detail; the steamer dock on Sugar Island looked draped in rain. He remembered that. It was a wet, middling season in Michigan; he forgot which one. There were a number of them. And this: the condemned freighter Maida towed by tugs toward a chalky wafer of sun, toward the lead-white expanse of Detroit River, black gleaming derricks, slag — the whole, lurid panorama of cloacal American nature smarm debouching into Lake Erie where — when Payne was duck hunting — a turn of his oar against the bottom brought up a blue whirring nimbus of petroleum sludge and toxic, coagulant effluents the glad hand of national industry wants the kids to swim in. This was water that ran in veins. This was proud water that wouldn’t mix. This was water whose currents drove the additives aloft in glossy pools and gay poison rainbows. This was water the walking upon of which scarcely made for a miracle.

Moping on an abandoned coal dock, Payne rehearsed his imagined home. He tried by main force to drag back the bass-filled waters he actually remembered. He dreamed up picturesque visions of long packed lawns planing to the river and the lake in a luminous haze beyond. He recollected freighters and steamers sailing by, the side-wheeled and crystal-windowed palaces of the D & C Line that had so recently gone in stately parade up the Canadian channel, the sound of their orchestras borne across the water to Grosse Ile.

But this time the Maida toiled before him on the septic flow, vivid with arrows of rust thrusting downward from dismal scuppers. On deck, a handful of men rather specifically rued the day. Life in the U.S.A. gizzard had changed. Only a clown could fail to notice.

So then, failing to notice would be a possibility. Consequently, he fell in love with a girl named Ann who interested herself in the arts, who was quite beautiful and wild; and who, as no other, was onto Payne and who, to an extent that did not diminish him, saw through Payne. In the beginning, theirs was one of those semichemical, tropistic encounters that seem so romantic in print or on film. Ann had a beautiful, sandy, easy and crotch-tightening voice; and, responding to it, Payne had given her the whole works, smile after moronic smile, all those clean, gleaming, square, white teeth that could only be produced by a region which also produced a large quantity of grain, cereals and corn — and stopped her in her tracks to turn at this, this what? this smiler , his face corrugated with the idiocy of desire and the eclectic effects of transcontinental motorcycle windburn, a grin of keenness, blocky, brilliant, possibly deranged. And stared at him!

He went to her house. He croaked be mine from behind the rolled windows of his Hudson Hornet which in the face of her somewhat handsome establishment appeared intolerably shabby. He felt a strange tension form between his car and the house. The mint-green Hornet was no longer his joy. The stupid lurch of its paint-can pistons lacked an earlier charm. The car was now spiritually unequal to him. The wheel in his hands was far away, a Ferris wheel. The coarse fabric of the seats extended forever. All gauges: dead. The odometer stuttered its first repetition in 1953 when Payne was a child. A month ago he’d had a new carburetor installed. When he lifted the hood, it sickened him to see that bright tuber of fitted steel in the vague rusted engine surfaces. The offensive innocence of mushrooms. A thing like that takes over. A pale green spot on a loaf of bread is a fright wig inside of a week. These little contrasts unhinge those who see them. The contrast between his car and her house was doing that now. He could barely see through the windshield, but clear glass would have been unendurable. The world changed through these occlusions. Objects slid and jumped behind his windshield as he passed them. He knew exactly how a building would cross its expanse progressively then jump fifteen degrees by optical magic. Don’t make me go in that house. Just at the center of the windshield a bluish white line appeared like a tendril turning round itself downward and exploded in a perfect fetal lizard nourished by the capillaries that spread through the glass.

Gradually, he worked himself from the machine, went to the door, was admitted, went through to the back where Ann Fitzgerald was painting a white trellis and, paint brush in her right hand, dripping pale paint stars in the dirt. “Yes,” she said, “I will.” Indicating only that she would see him again. “Stay where you are,” she said. An instant later she photographed him with a large, complex-looking camera. “That will be all,” she smiled.

The steamer dock, the former property of the Sugar Island Amusement Company, defunct 1911, was a long balconied pier half-slumped under water. Near the foot of the pier, abandoned in the trees, was an evocative assortment of pavilions, ticket stands and stables. There were two carved and lofty ramps that mounted, forthright, into space. And the largest building, in the same style as the pavilion, was a roller rink. This building had come to be half-enveloped in forest.

It was nighttime and the ears of Nicholas Payne were filled with the roar of his roller-skated pursuit of the girl, Ann, at speed over the warped and undulant hardwood floor. He trailed slightly because he glided down the slopes in a crouch while she skated down; and so she stayed in front and they roared in a circle shuddering in and out of the light of the eight tall windows. Payne saw the moon stilled against the glass of one unbroken pane, gasped something like watch me now and skated more rapidly as the wooden sound sank deeper into his ears and the mirrored pillar that marked the center of the room glittered in the corner of his eye; he closed the distance until she was no longer cloudy and indefinite in the shifting light but brightly clear in front of him with the short pleatings of skirt curling close around the soft insides of thigh. And Payne in a bravura extension beyond his own abilities shot forward on one skate, one leg high behind him like a trick skater in a Dutch painting, reached far ahead of himself, swept his hand up a thigh and had her by the crotch. Then, for this instant’s bliss, he bit the dust, hitting the floor with his nose dragging like a skeg, landing stretched out, chin resting straight forward and looking at the puffy, dreamy vacuity midway in her panties. Ann Fitzgerald, feet apart, sitting, ball-bearing wooden wheels still whirring, laughed to herself and to him and said, “You asshole.”

2

It was one of those days when life seemed little more than pounding sand down a rat hole. He went for a ride in his Hudson Hornet and got relief and satisfaction. For the time allowed, he was simply a motorist.

After the long time of going together and the mutual trust that had grown out of that time, Payne had occasion to realize that no mutual trust had grown out of the long time that they had gone together.

He had it on good evidence — a verified sighting — that Ann was seeing, that afternoon, an old intimate by the name of George Russell. There was an agreement covering that. It was small enough compensation for the fact that she had lit out for Europe with this bird only a year before, at a time when the mutual trust Payne imagined had grown up between them should have made it impossible to look at another man. Afterwards, between them, there had transpired months of visceral blurting that left them desolated but also, he thought, “still in love.” Now, again, George Russell raised his well-groomed head. His Vitalis lay heavy upon the land.

The affair of Payne and Ann had been curious. They had seen each other morning, noon and night for the better part of quite some time. Her parents, Duke and Edna Fitzgerald, were social figments of the motor money; and they did not like Nicholas Payne one little bit. Duke said he was a horse who wasn’t going to finish. Edna said he just didn’t figure.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Bushwacked Piano»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Bushwacked Piano» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Bushwacked Piano» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.