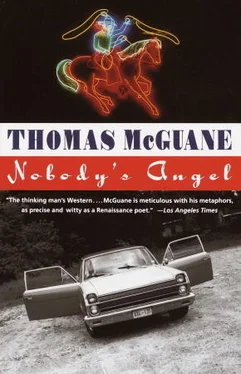

Thomas Mcguane

Nobody's Angel

This book is for my beloved Laurie,

still there when the storm passed

“I love hell. I can’t wait to get back.”

— MALCOLM LOWRY

YOU WOULD HAVE TO CARE ABOUT THE COUNTRY. NOBODY had been here long enough and the Indians had been very thoroughly kicked out. It would take a shovel to find they’d ever been here. In the grasslands that looked so whorled, so cowlicked from overhead, were the ranches. And some of these ranches were run by men who thought like farmers and who usually had wives twice their size. The others were run by men who thought like cowboys and whose wives, more often than not, were their own size or smaller, sometimes quite tiny. The farmer-operators were good mechanics and packed the protein off the land. The cowboys had maybe a truck and some saddle horses; and statistics indicate that they had an unhealthy dependence on whiskey. They were not necessarily violent nor necessarily uneducated. Their women didn’t talk in the tiny baby voices of the farmer-operator wives nor in the beautician rasp of the town wives. The cowboys might have gotten here last week or just after the Civil War, and they seemed to believe in what they were doing; though they were often very lazy white men.

The town in the middle of this place was called Deadrock, a modest place of ten thousand souls, originally named for an unresolved battle between the Army and the Assiniboin — Deadlock — but renamed Deadrock out of some sad and irresolute boosterism meant to cure an early-day depression. To many people Deadrock was exactly the right name; and in any case it stuck. It was soon to be a major postcard.

Patrick Fitzpatrick lived on a ranch thirty-one miles outside of town. He was a forth-generation cowboy outsider, an educated man, a whiskey addict and until recently a professional soldier. He was thirty-six years old. He was in good shape; needed some crown work but that was about it.

THE YARD LIGHT ERECT UPON ITS WOOD STANCHION THREW down a yellow faltering glow infinitely chromatic falling through the China willow to the ground pounded up against the house by the unrepentantly useless horses. Patrick Fitzpatrick glided under the low branches on his mare as the band circled into the corral for salt and grain and water and the morning’s inspection for cracked hooves, lameness, splints, bowed tendons, lice, warbles, wire cuts, ulcerated eyes, wolf teeth, spavin, gravel, founder and worms.

Near the light’s edge the dogs watched him pass: Cole Younger, yellow, on his back, all four legs dangling, let his eyelids fall open upside down; Alba, black, in the sub-shadow of mountain ash, ready to run; Zip T. Crow, brindle, jaw alight on parallel front legs, considered starting a stampede with his hyena voice. Thinking finally of the consequences, he fell to dreaming as the last horse, a yearling running at an angle, jog-trotted into the corral to drink in the creek alongside the other shadowy horses deployed as regularly as a picket line. Zip T. Crow slunk over behind some relic of a walking cultivator and dropped into its confused shadows like a shy insurrectionist. This was the day to ride up to the airplane.

IN VERY EARLY SPRING BEFORE THE CREEKS FLOODED, BEFORE the first bridges washed away and the big river turned dark, before the snow was gone from the rugged shadows and the drowned livestock tumbled up in the brushy banks, Patrick found the airplane with his binoculars — a single ripped glimmer of fuselage visible a matter of hours before the next flurry concealed it for another month but not before Patrick had memorized the deep-blue ultramontane declivity at the top of the fearsome mountain and begun speculating if in May he could get a horse through the last ten thousand yards of deadfall and look into the pilot’s eyes. Patrick was the son of a dead pilot.

Then in May Patrick walked up the endless sloping nose and saw the pilot quite clearly. He climbed past him to the copilot’s seat and found fractured portions of granite, parts of the mountain that had poured like grapeshot through the fuselage clear into the tail section, leaving the copilot in innumerable pieces, those pieces gusseted in olive nylon, and the skin of the aircraft blood-sprayed as in a cult massacre. Farther aft in the tapering shape where the beating spring sun shone on the skin of the plane and where viscera trailed off in straps, fastening and instruments, it stank. Arms raised in uniform, the pilot seemed the image of a man in receipt of a fatal sacrament. The oxygen hose was torn away, and beyond the nautiloid effigy, Patrick could see his mare grazing on the alpine slope. Unable to differentiate flesh and electronics, he was avoiding the long-held notion that his father had died like a comet, igniting in the atmosphere, an archangelic semaphore more dignified than death itself. For Patrick, a year had begun. The inside of the plane showed him that life doesn’t just always drag on.

PATRICK LEFT THE SIDEWALK THROUGH THE DOOR BETWEEN the two angled windows. It was cold, but when he hung his coat inside and glanced onto the street, it looked like summer. Purest optics. There was a stock truck parked at the hotel with two saddled horses in back facing opposite directions. Many saddle horses spend the day parked in front of a bar, heads hung in sleep. Can’t get good help anymore, Patrick thought. Even if you could, who wants to tell people what to do?

Two steps up at the poker table was an old man with a diamond willow cane pushing chips onto the green felt. There was a belton setter at his feet, two strangers and a girl dealing cards. Not strangers, but he couldn’t remember their names.

“Afternoon, Patrick,” said the old man, whose name was Carson. That was his first name.

One stranger said, “Hello, Captain”—Patrick had been in the Army — and the other said, “How’s the man?” Classmates with forgotten faces. But Patrick was rather graceful under these conditions, and by the time he’d gone through the room, the setter was asleep again, the players were smiling and the girl dealing was reading his name off the back of his belt.

The bar was nearly empty, populated solely by that handful of citizens who can drink in the face of sun blazing through the windows. Patrick ordered his whiskey, knocked it back and reconnoitered. Whiskey, he thought, head upstairs and do some good.

He called, “Thanks so much!” to the bar girl, put down his money and left. It was hard to leave a place where God was at bay.

He walked all the way to the foot of Main, straight toward the mountain range, crossed the little bridge over the clear overflow ditch and went into a prefabricated home without knocking. The windows were covered with shades, and once his eyes accustomed themselves to the poor light, he could see the prostitutes on the couch watching an intelligent interview show, the kind in which Mr. Interlocutor is plainly on amphetamines, while his subjects move in grotesque slow motion. They were dealing with the fetus’s right to life. On the panel were four abortionists, five anti-abortionists and a livid nun with the temper of an aging welterweight.

“Hello, girls.”

“Hello, Patrick.”

“No game on?”

“College basketball. We’re watching this fetus deal.”

“Anybody make a profit?”

“Loretta did.”

Loretta, a vital brunette with tangled hair and a strong, clean body, beamed. She said, “Trout fishermen. Doctors, I think. One had a penlight. He said he always checked for lesions. I said clap. He said among other things. I said four- to ten-day incubation. He says which book are you reading. I said I don’t read books, I watch TV. So he gets in there with this penlight. I could’ve swatted him.”

Читать дальше