Let’s have this quickly now: At Galveston, Ann wired for money, a lot of it, waited three hours, got it, flew to Dallas, took a room, called George and gave him the yes he had waited for so many years. Hearing his tears, his gratitude, she made reservations on Delta to fly up the next day; then, headed for Neiman-Marcus.

So that: She ran across the tarmac at Detroit-Metropolitan Airport, adorable in a little mini-caftan by Oscar de la Renta made of pink linen. Over that she wore a delicate Moroccan leather coat. The sandals were Dior; and their blocky little heels looked like ivory. Anyone who says she wasn’t darling has another think coming.

And George ran to her perfectly attired in an impeccably tailored glen plaid from J. Press. What seemed almost risky in his livery was the wild, yellow Pucci cravat that precisely counterpointed his sedate, seamless cordovans from Church of London.

See them, then, running thus toward one another: perfect monads of nullity.

They whirled in one another’s arms.

“Darling,” Ann said, “I’ve been through much.” She had caught a little cold aboard ship and George was very, very concerned. After gathering her luggage, they went directly to a hotel where George greedily massaged her chest with Vick’s Vap-O-Rub.

It is quite true that George hired the gallery. Nevertheless, Ann’s first show was reviewed legitimately; and was a success. Probably the quarterly critic, Allan Lier, of Lens magazine, represents the consensus:

… Miss Fitzgerald’s striking available-light photographs of commercial fishermen turning in for the night are the best sequence of the show. Frame after frame, we see these tired men backlit against the hatchway, heading for a long-earned rest. In their impatience and exhaustion, they are already in various stages of undress.

By way of contrast, the group of pictures called “Nicholas” introduces us to a private yet utterly communicated vision of what is lost in the conventional life. We see time and time again the same weary face of Nicholas: the ‘shy suitor,’ the spurious rodeo cowboy, the motorist. In one superb shot, in a claustrophobic laundry room, Nicholas is drubbed over the head with a toilet plunger by an attractive older woman: It is left to the viewer to speculate as to what he has done to deserve this! In another picture, he stares directly into the camera, apparently about to speak but unable to think of a single thing to say. In the most terrifying picture of them all, he rises from a toilet seeming to spring at the camera. He wears a short institutional shift and we see where his mediocrity leads. Nothing that is said here can communicate the banality which Miss Fitzgerald captures with polish and control. Thanks to her craft, humanity and attention, she has delivered a cautionary monument to the failed life.

See this show at once.

Payne headed North, making two stops in the State of Florida. One was to see Junior Place and inspect the bat cave with him; the tower bats had not been rejected by their friends and hung upside down from the roof of the cave like thousands of Indian River oranges.

He stopped on the Georgia border and bought an M. Hohner Marine Band harmonica and spent the better part of an evening failing to play Hank Williams’ “I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive.”

A truck drove by with a sign: HOLD UP YOUR PACK OF AMERICAN SPACE. The question was whether he had actually seen that. That was getting to be the real question all right.

On a lonely beach in the Sea Islands, Nicholas Payne unfolded his camp stove and began to prepare his supper. He could smell the sea and the sandy groves of loblolly pine that throbbed with uncommon birds. Turned at an angle to the homemade trailer whose floor smelled balefully of departed bats, the Hudson Hornet pointed to the interior of the continent.

Payne poised a jacknife spread with peanut butter over a rigid piece of bread and lifted his face to the sea. He felt as if he had been made an example of; and that, even now, he was part of a demonstration, an exhibit. He held the knife and peanut butter steady. The sky rose over him, round and vitreous, a glass enclosure. He smiled, at one with things. He knew the great blenders hummed in state centers and benign institutions; while he, far away, put it all together at a time when life was cheap.

But then the abrasions, all the incredible abrasions, had rendered him. The pale, final shape of Payne, like the yolk of an egg held to the light, had come to be seen.

I am at large.

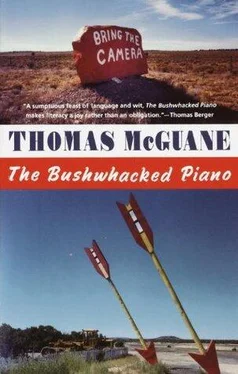

Thomas McGuane is the author of several highly acclaimed novels, including The Sporting Club; The Bushwhacked Piano , which won the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Award of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters; Ninety-two in the Shade , which was nominated for the National Book Award; Panama; Nobody’s Angel; Something to Be Desired; Keep the Change ; and Nothing but Blue Skies . He has also written To Skin a Cat , a collection of short stories; and An Outside Chance , a collection of essays on sport. His books have been published in ten languages. He was born in Michigan and educated at Michigan State University, earned a Master of Fine Arts degree at the Yale School of Drama and was a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford. An ardent conservationist, he is a director of American Rivers and of the Craighead Wildlife-Wildlands Institute. He lives with his family in McLeod, Montana.