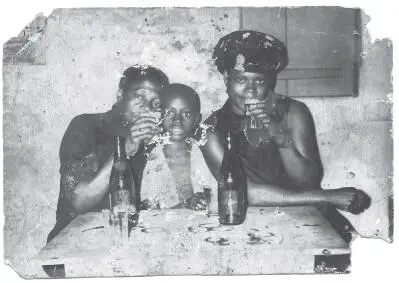

‘Stop prattling and tell us how much the photo costs!’

Mr Hasselblad SWC struck up a ridiculous pose with his camera and, in the blink of an eye, the flash exploded in our faces…

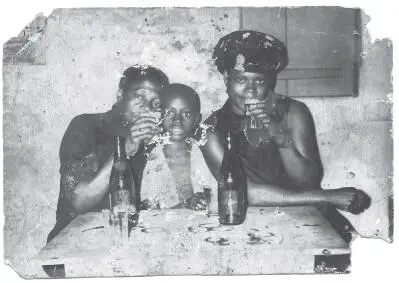

The photo looks different to me now. Perhaps because I’m looking at it in the town where it was taken. It’s as though in Europe or in America it keeps its secrets hidden. I look more closely. My mother dominates the picture. All you see, practically, is her and the scarf round her head. She seems more relaxed than my father and I, who are both trying to squeeze into the small amount of space she’s left us. She wanted to be the one people saw when they looked at the photo. We were just there to highlight her presence, the principal’s impact being very much dependent on the involvement of those playing the secondary roles. This was clearly the impression she wished to create, with the way she is leaning slightly to the right, as though my father and I no longer existed, or as though we were intruding on what she considered her moment of glory, which she would leave for posterity.

She is looking at the camera lens with a little smile, showing she has found the perfect pose. She doesn’t know I’ve got my mouth open, a blank expression, big wide eyes that seem to be asking what the point of this photo is. Normally she would have reminded me:

‘Sit up straight, look, we’re having our picture taken!’

She’d have told me to close my mouth, she didn’t like this expression, considering it unworthy and unflattering.

My shirt is hanging open — perhaps I had lost my buttons again, ‘like an idiot’, as my mother would have said. I admit that buttoning up my shirt was not a priority. I often had my shirt with all the buttons in the wrong holes.

Now I notice various details that I haven’t seen before. For example, my mother’s right shoulder seems to be crushing me, while my father’s trying to keep us propped up. That’s why his head is pressed up against mine. I can see, too, my father’s fingers on my mother’s left shoulder. I think it must be his left arm holding us up and without it we wouldn’t have managed to hold the pose. Lastly, the marks left by the bottles on the surface of the table suggest the waiters didn’t wipe them very often…

I called her ‘Grandma Hélène’, but she was really my aunt, and she lived in the rue de Louboulou, just behind Uncle Albert’s house. She went everywhere barefoot, and stopped outside every house to offer vegetables, fruit, manioc, foufou or a demijohn of palm wine. Grandma Hélène was one of those people who you think has to have been born old, toothless, white haired, hesitant in her movements, like a stray gastropod, it was so impossible to imagine her young. You couldn’t tell her age, she didn’t know herself, having lived her entire life without an identity card or a birth certificate. In her day, to obtain such documents, you had to pay a visit to the colonial authorities, who measured your height, inspected the state of your teeth and made a guess at an approximate year of birth with the famous expression: ‘Born around…’. Neither her husband, Old Joseph, nor she herself ever bothered to do this, particularly since several of the traditional chiefs, whose opposition to the colonial administration took particularly imaginative forms, spread rumours to the effect that the whites had a secret plan: anyone who agreed to have civil papers drawn up for them would have their souls carried off to Europe. These individuals would once again become slaves, and would undergo the fateful ‘voyage’ of the slave trade, which would take them, via Europe, all the way to America, where they would be sold to the highest bidder and set to work from dawn to dusk in plantations owned by their brutal masters. According to these highly placed sources, this was how the whites had created the slave trade, knowing they would never have the physical strength to confront the blacks and take them captive. Fear ruled, like the fear that gripped the villagers when the first cameras arrived in their land. At the time every possible argument — most of them outlandish in the extreme — was used to dissuade people from allowing themselves to be photographed. Just look at Europe, which only managed to keep going by hijacking souls and spirits. They spoke admiringly of their ancestors, who, when photographed against their wishes, simply didn’t appear on the image, because they were more mystical than the white man, and had taken the precaution of covering their souls with a kind of anti-flash cover.

In any case, no one would have asked Grandma Hélène or her husband their age, it would have implied they were too old and should be thinking about moving on to that distant country where, the Bembé believe, the sun never rises. Old Joseph looked so strong, people always thought he must be several years younger than his wife. A man of few words, he would sit out in the sun — source of all longevity, he believed — and thoughtfully watch time passing, just sitting on his own front doorstep. His left eye was useless, the entire surface of the pupil covered over by a large, pale tumour. He could now see only through the other eye, but even so, not one detail of the comings and goings in his yard escaped him. Some were afraid of his sickly eye, rambling on about the old man using it in the dark to find out the sorcerers’ tricks and foil them, before it was too late.

Their firstborn daughter, Mâ Germaine, seemed as old as them. There was a rumour that the couple had handed down the secret of long life to their descendants. Grandma Hélène was aware of this, and would babble crossly:

‘We’re already old, age has forgotten us, and we’ve forgotten it too. That’s the secret of our longevity…’

Old Joseph was rather overshadowed by Grandma Hélène, but she herself led a busy life, to say the least, continually checking that no one she knew wore a mask of despair. If they did, she would go over to them, lift it off, and mumble some comforting words, assuring them things would be much better tomorrow. She’d been nicknamed ‘Mother Teresa’ because though she had more than ten children under her roof she put the interests of others even before those of her own offspring. Idle gossips were quick to imply that each time you got a gift from Grandma Hélène she took a year off your life to extend her own and that of her husband and children. Hence the uncouth manner in which some people rejected the old lady’s generosity, accusing her of being a witch.

In actual fact, in all the time since she arrived from Louboulou she had never grown used to the idea that everything here was different, and that life in the city was unlike life back in the village in every way. Here an act of kindness drew suspicion. There it was a sacred duty, designed to keep the ungrateful, the selfish and individualists away from the village. In her mind, Pointe-Noire, and in particular the rue de Louboulou, was her village, it had simply been relocated, and because of this she had an obligation, as a peasant woman in possession of vast plantations in her home country, to share what she possessed with the population, whoever they were, that was the way she had been brought up.

She was so highly respected, she had become like a patriarch of the tribe, a kind of protective presence, even, watching over our family and the inhabitants of the rue de Louboulou. She would prepare food in a huge aluminium pot, then turn up in the street, grab hold of any child who happened to be passing, and sit them down in front of a large, steaming portion. Gluttons were only too delighted, along with various parasites and outright crooks, who knew you only had to drift past her house at mealtimes to get yourself a square meal. Which is probably why several adults could be found pacing up and down her yard, emerging fit to burst, like boa constrictors who’ve swallowed an antelope. We children, on the other hand, didn’t hang around her that much; to us her generosity felt like a punishment in disguise, particularly as once we had finished eating Grandma Hélène would applaud, then say, with a great big smile:

Читать дальше