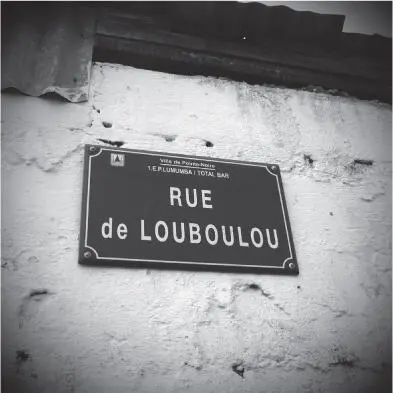

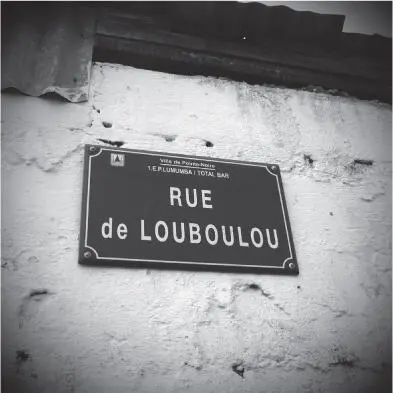

The city council agreed to Uncle Albert’s request, after he’d paid backhanders to a few of the government employees who then came and raised their glasses, shamelessly, at the renaming ceremony for the street. Every week members of the family would drop in to see Uncle Albert, and when he withdrew into his bedroom you knew he would re-emerge with some money to give the visitor. Broadly speaking, though it was not to be said out loud, you went round to Uncle Albert’s in the hope of leaving again with a few thousand CFA francs. If people arrived while he was having his siesta they would hang around in the yard, pretending to chat with Gilbert and Bienvenüe, my uncle’s twins, my cousins, with whom I spent much of my childhood. The twins understood what was going on, and sensed that their father was basically the family bank. Sometimes, so he wouldn’t be disturbed while he was resting, Uncle Albert would place a packet of banknotes on the table and leave it to his wife, Ma Ngudi, to distribute them to the various visitors.

My mother would also stop off at the rue de Louboulu. Not to pick up money, but to hand some over to Ma Ngudi, because I sometimes lived at my uncle’s for a while. Maman Pauline had requested this, ‘in the interests of Albert’s nephew’. Ma Ngudi was said to be good with children who didn’t eat enough — sometimes I would eat only the meat, and leave the fufu and manioc.

One evening my mother came to pick me up at Uncle Albert’s, and Marcel, my father’s bête noire, just happened to be hanging around close by. By pure coincidence, Papa Roger, on his way back from work, had also decided to thank my uncle and his wife for having me to stay with them, and probably to leave a little envelope for my cousins Bienvenüe and Gilbert, as he often did.

My mother and I were still saying goodbye to Uncle Albert when we heard a great rumpus out in the street. It had to be a fight, because all the kids in the neighbourhood were shouting:

‘Ali boma yé! Ali boma yé! Ali boma yé!’

It was the famous cry of the Zaireans at the ‘May 20th’ Stadium during the legendary fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. In both Congos, it had become customary to chant it at any brawl.

We all dashed outside into the street, and found a real punch-up going on, which had brought the entire Rex neighbourhood running to the rue du Louboulou. Marcel and my father were on the ground, covered in dust, and Papa Roger was on top, despite being so much smaller than the other guy, who seemed to me to be some kind of colossus, measuring nearly two metres, a good head taller than most houses in the street. Each time Marcel tried to get to his feet and catch my father off guard, the local people, including several members of our family, caught hold of his shirt or one of his feet, and he lost his balance again, to Papa Roger’s advantage. Picking a fight in the middle of this group, where we were as good as joined at the hip, was equivalent to signing his own death warrant.

My mother yelled at the top of her voice:

‘Roger! Leave the guy alone! He hasn’t done anything!’

My father wouldn’t let go of Marcel’s neck.

‘I’ll kill him! I’ll kill him!’

Buoyed up by the excitement of the group, he was leaping around, striking karate poses which he’d seen in the film The Wrecking Crew , butting him, kicking him, kneeing him, and again, till Marcel, his face all bloodied, managed to work himself free and make a run for it. The whole neighbourhood ran after him. Everyone had a piece of wood or a stone in their hands.

‘They’ll kill him!’ shrieked my mother.

‘We sure will!’ came a voice from the crowd.

You couldn’t tell who was throwing the stones and who the bits of wood, which Marcel was just managing to dodge. He had long legs and ran as though death itself was at his heels. In a few strides he crossed the Avenue of Independence and vanished into thin air in the winding streets of the Trois-Cents neighbourhood, the haunt of the prostitutes from Zaire. His pursuers knew not to go looking for him on that territory, where a fight could quickly turn into a general riot.

Back at our house, my parents were rowing fiercely. My mother was telling my father it was a coincidence that Marcel happened to be in the rue de Louboulou. My father didn’t believe her, and was convinced that Maman Pauline had arranged a meeting with him, and that Uncle Albert was in on it, as were the entire Bembé tribe in the rue de Louboulou.

‘So then why did the very people from my tribe that you’re accusing take your side?’

My father didn’t answer that. Proof, perhaps, that he realised my maternal family had been rooting for him, and he’d been carried away by suspicion and rage…

The photo’s in black and white, with a bit torn off at the bottom, on the right-hand side. It was taken at the end of the 1970s, one afternoon in the Joli-Soir district. I had come to meet my parents in this bar, where we are all sitting at a table. The two of them have glasses raised to their lips, and mine is on the table. It’s filled with beer, my mother insisted on this, she didn’t want anyone to think I was only there for the photo. We had to make it look like I had been sitting drinking with them for some time. I can still hear my mother acting like some finicky film director, to the photographer’s slight surprise:

‘Hold on, monsieur, we’re not ready! First get rid of those flies buzzing round the table! A fine way to mess up people’s photos! I’ll tell you when to press the button!’

She swept her eyes across the room, hoping she could put off the moment when he took the picture. A few people entered and were making their way to the back of the bar. She grabbed her chance:

‘What’s all this, then? Did you see that? You can’t even take a photo in this country these days, not since President Marien Ngouabi died! Tell them to stop coming in for a moment!’

Then, turning her attention to us:

‘And you two, act as though the photographer wasn’t there! Especially you, Roger, whenever someone takes your photo you look all tensed up like a snail that doesn’t know which way to turn! What way is that to behave? And you, boy, sit properly now. Sit up straight like a boy scout, like a boy who’s proud to be sitting there between his papa and mama!’

Despite all these precautions, at which the photographer’s annoyance grew, she failed to notice a fourth glass on the table, to my left, in front of Papa Roger. He had bought a drink for the photographer, who had knocked it back in one, without saying thank you, eager to get on with the serious business. Instead of moving his glass out of the way, he had left it there. He seemed completely overwhelmed by his job, which, in order for him to make any money at all, required him to go all round town, from one bar to another, persuading people to have their photos taken. He wrote down your address in an old notebook and came round to your house the next day with the picture. You had to pay him a deposit beforehand. He made sure to print several copies of the same image, since if it turned out to be a masterpiece, everyone was going to want one. He was known in most districts of Pointe-Noire by now. And that day he was blowing his own trumpet in front of my parents, saying:

‘I’m the only one in this town with a Hasselblad SWC! Even the Americans used one when they went up into space! Do the other photographers in this town have one? No they do not! Just me! That’s why they call me Mr Hasselblad SWC!’

Could anyone verify his claims? No one understood his gibberish anyway, all you saw was him pressing a button, and a flash that went off just like on any other camera. But my mother cut him short:

Читать дальше