“Her worst fault,” I said (Baxter at once looked indignant) “is her infantile sense of time and space. She feels short intervals are huge, yet thinks she can grasp all the things she wants at once, no matter how far they are from her and each other. She talked as if her engagement to marry me and her elopement with Wedderburn were simultaneous. I had no heart to tell her time and space forbid this. I did not even explain that the moral law forbids it.”

Baxter was halfway through explaining that our ideas of time, space and morality were convenient habits, not natural laws, when I yawned in his face.

There was daylight and bird-song outside the window. Mournful hooters were summoning workers into shipyards and factories. Baxter said a bed was prepared for me in a guest-room. I answered that I would be on duty in a couple of hours and wanted nothing from him but the use of a wash-basin, razor and comb. As he led me upstairs he said, “We have talked about Bella exactly as she foretold in her letter, so you had better live here too. I ask this as a favour, McCandless. The company of elderly women is not enough for me now.”

“Park Circus is very far from the Royal Infirmary compared with my digs on the Trongate. What would your terms be?”

“A rent-free room with free gas-light, free coal fire and free bed-linen. Free laundering of your small clothes and shirts, free starching of your collars, polishing of your boots. Free hot baths. Free meals when you choose to eat with me.”

“Your food would sicken me, Baxter.”

“You would be given the same meals Mrs. Dinwiddie and the cook and housemaid give themselves — plain fare excellently cooked. You would have the free use of a good library which has been greatly enlarged since Sir Colin’s time.”

“And in return?”

“When you have a spare moment you could help me in the clinic. From dogs, cats, rabbits and parrots you may learn much to help you mend featherless bipedal patients.”

“Hm! I will think it over.”

He smiled as if he thought my remark an empty show of manly independence. He was right.

That evening I borrowed a big trunk, packed it, paid my Trongate landlord a fortnight’s rent for notice of quittal, and came in a cab to Park Circus with all my goods, gear and chattels. Baxter received me without comment, showed me my new room and handed me a telegram wired from London a few hours before. It said M HR (am here) with no name at the end.

If hard rewarding work, interesting, undemanding friendship, and a comfortable home are the best grounds for happiness then the following months were perhaps the pleasantest I have known. All Baxter’s servants had begun life as country girls of my mother’s class, and though none were much less than fifty I believe they liked having a comparatively young man in the house who enjoyed the food they prepared. They never saw me eat because my meals were hoisted up to the dining-room on a dumb-waiter, but I often sent a cheap bunch of flowers or note of thanks down to the kitchen with the dirty plates.

I ate with Baxter at a huge table, sitting as far from him as possible. Having little or no pancreas he made his digestive juices by hand, stirring them into his food before chewing and swallowing. When I asked about the ingredients he evaded the question in a shamefaced way which suggested some were extracted from his bodily wastes. The odour at his end of the table confirmed this. Behind his chair was a sideboard loaded with carboys, stoppered vials, graduated glasses, pipettes, syringes, litmus papers, thermometers and a barometer; also the Bunsen burner, retort and tubing of a distillation plant. This last bubbled on a low gas throughout the day. At unpredictable moments in every meal he would stop chewing and stay absolutely still as if listening to something remote, yet inside himself. After seconds like this he would slowly stand, carefully carry his plate to the sideboard and spend minutes concocting messes for addition to it. On the sideboard lay a chart where every four hours he recorded his pulse, respiration and temperature, besides chemical changes in his blood and lymphatic system. One morning before breakfast I studied it and was so disturbed that I never looked at it again. It showed daily fluctuations too irregular, sudden and steep for even the strongest and healthiest body to survive. Times and dates (noted in Baxter’s clear, tiny, childish yet firm script) showed that when talking to me the day before his neural network had passed through the equivalent of an epileptic seizure, yet I had noticed no change in his manner. Surely all this apparatus and charting must be pretences, ploys by which an ugly hypochondriac exaggerated his diseases in order to feel superhuman?

Outside the dining-room life at 18 Park Circus was splendidly commonplace. After the evening meal we tended the sick animals in the operating-theatre, then retired to the study where we read or played chess (which Baxter always won) or draughts (which I nearly always won) or cribbage (where the victor was unpredictable). We resumed our long weekend tramps and all the time talked about Bella. She did not let us forget her. Every three or four days a telegram saying “M HR” arrived from Amsterdam, Frankfort-on-Maine, Marienbad, Geneva, Milan, Trieste, Athens, Constantinople, Odessa, Alexandria, Malta, Morocco, Gibraltar and Marseilles.

One foggy November afternoon came a telegram from Paris saying DNT WRRY. Baxter grew frantic. He cried, “There must be something dreadful to worry about if she tells me not to do it. I will go to Paris. I will hire detectives. I will find her.”

I said, “Wait till she summons you, Baxter. Trust her honesty. That message means she is not disturbed by an event which would upset you or me. Rather than thwart her you trusted her to Duncan Wedderburn. Better trust her to herself, now.”

This convinced but did not calm him. When the same message came from Paris exactly a week later his resolution collapsed. I went to work one morning feeling sure he would have left for France when I got back, but as I entered the front door he hailed me vigorously from the study landing shouting, “News of Bella, McCandless! Two letters! One from a maniac in Glasgow and one from her residence in Paris!”

“What news?” I cried, casting off my coat and running upstairs. “Good? Bad? How is she? Who wrote these letters?”

“The news is certainly not altogether bad ,” he said cautiously. “In fact, I think she is doing remarkably well, though conventional moralists would disagree. Come into the study and I will read the letters to you, leaving the best till last. The other one has a south Glasgow postmark, and a maniac wrote it.”

We composed ourselves on the sofa

He read aloud what follows.

41 Aytoun Street,

Pollokshields .

November 14th .

Mr. Baxter,

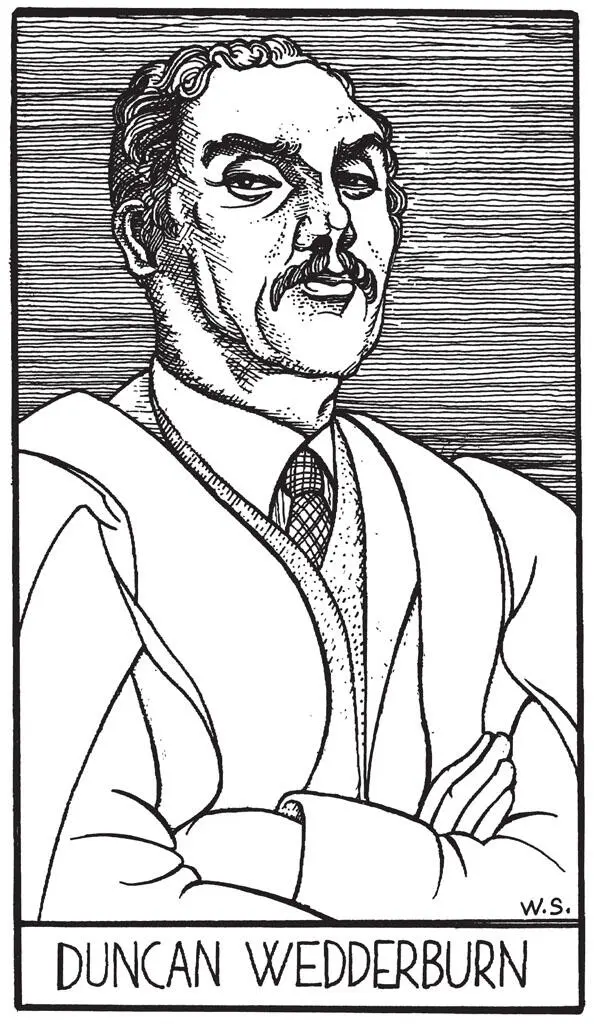

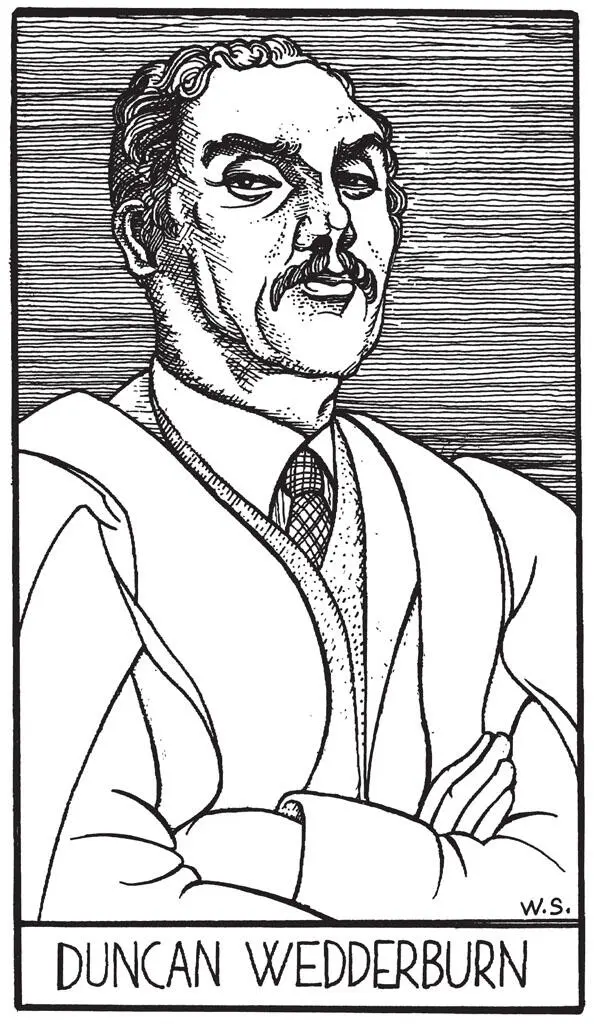

Until a week ago I would have been ashamed to write to you, sir. I then thought my signature on a letter would convulse you with such loathing that you would burn it unread. You invited me to your home on a matter of business. I saw your “niece”, loved her, plotted with her, eloped with her. Though unmarried we toured Europe and circled the Mediterranean in the character of husband and wife. A week ago I left her in Paris and returned alone to my mother’s home in Glasgow. Were these facts made public The Public would regard me as a villain of the blackest dye, and that, until a week ago, is how I viewed myself: as a guilty reckless libertine who had ravished a beautiful young woman from her respectable home and loving guardian. I now think much better of Duncan Wedderburn and far, far worse of you, sir. Did you see the great Henry Irving’s production of Goethe’s Faust at the Glasgow Theatre Royal? I did. I was deeply moved. I recognized myself in that tormented hero, that respectable member of the professional middle class who enlists the King of Hell to help him seduce a woman of the servant class. Yes, Goethe and Irving knew that Modern Man — that Duncan Wedderburn — is essentially double: a noble soul fully instructed in what is wise and lawful, yet also a fiend who loves beauty only to drag it down and degrade it. That is how I saw myself until a week ago. I was a fool, Mr. Baxter! A blind misguided fool! My affair with Bella was Faustian from the start, the intoxicating incense of Evil was in my nostrils from the moment you foisted me onto your “niece”. Little did I know that in THIS melodrama I would play the part of the innocent, trusting Gretchen, that your overwhelming niece was cast as Faust, and that YOU! YES, YOU, Godwin Bysshe Baxter, are Satan Himself!

Читать дальше