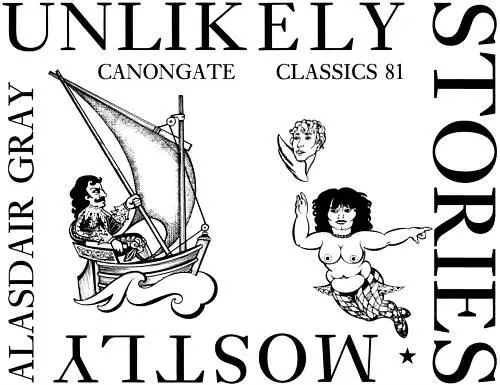

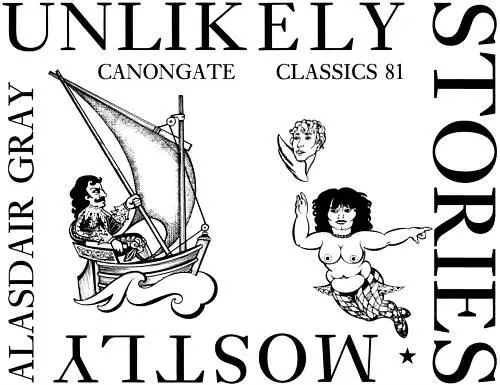

Alasdair Gray

Unlikely Stories Mostly

The Publishers apologise for

the loss of the erratum slip

UNLIKELY STORIES, MOSTLY

Alasdair Gray was

and educated

and became

residing

and remaining

and intending

then on

became in

and again

and later

and later

again.

He still is

and resides

and intends

and hopes

and may

,but

is certain to

one day.

They passed through the galleries, surveyed the vaults of marble, and examined the chest in which the body of the founder is supposed to have been deposited. They sat down in one of the most spacious chambers to rest for a whille, before they attempted to return.

“We have now,” said Imlac, “gratified our minds with an exact view of the greatest work of man, except the wall of China.

“Of the wall it is very easy to assign the motive. It secured a wealthy and timorous nation from the incursions of barbarians. But for the pyramids no reason has ever been given adequate to the cost and labour of the work. It seems to have been erected only in compliance with that hunger of imagination which preys incessantly upon life, and must always be appeased by some employment. He who has built for use till use is supplied, must begin to build for vanity, and extend his plan to the utmost power of human performance that he may not be soon reduced to form another wish.

“I consider this mighty structure as a monument to the insufficiency of human enjoyments. A government whose power is unlimited, and whose treasures surmount all real and imaginary wants, is compelled to solace the satiety of dominion by seeing thousands labouring without end, and one stone, for no purpose, laid upon another.”

From RASSELAS by Samuel Johnson

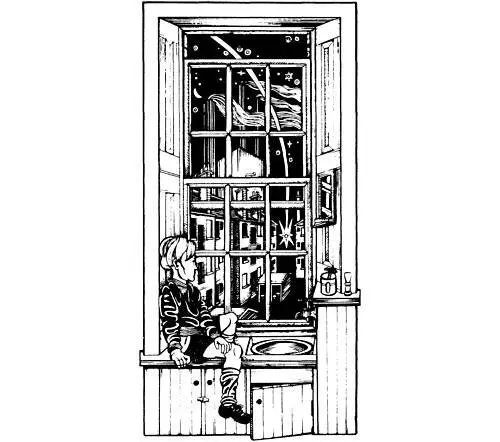

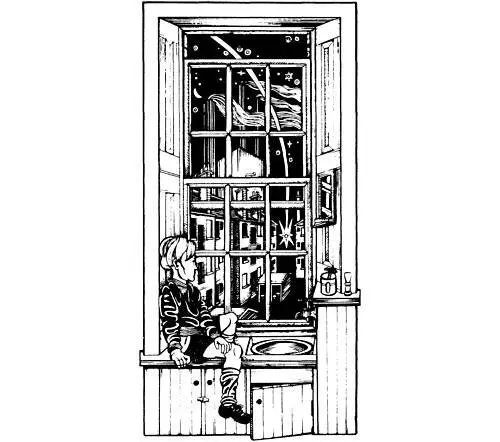

A star had fallen beyond the horizon, in Canada perhaps. (He had an aunt in Canada.) The second was nearer, just beyond the iron works, so he was not surprised when the third fell into the backyard. A flash of gold light lit the walls of the enclosing tenements and he heard a low musical chord. The light turned deep red and went out, and he knew that somewhere below a star was cooling in the night air. Turning from the window he saw that no-one else had noticed. At the table his father, thoughtfully frowning, filled in a football coupon, his mother continued ironing under the pulley with its row of underwear. He said in a small voice, “A’m gawn out.” His mother said, “See you’re no’ long then.”

He slipped through the lobby and onto the stairhead, banging the door after him.

The stairs were cold and coldly lit at each landing by a weak electric bulb. He hurried down three flights to the black silent yard and began hunting backward and forward, combing with his fingers the lank grass round the base of the clothes-pole. He found it in the midden on a decayed cabbage leaf. It was smooth and round, the size of a glass marble, and it shone with a light which made it seem to rest on a precious bit of green and yellow velvet. He picked it up. It was warm and filled his cupped palm with a ruby glow. He put it in his pocket and went back upstairs.

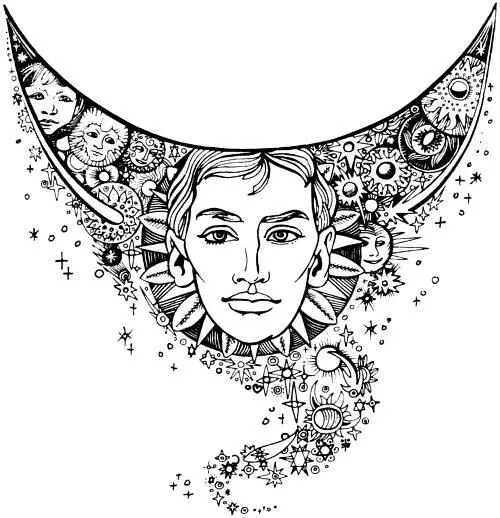

That night in bed he had a closer look. He slept with his brother who was not easily wakened. Wriggling carefully far down under the sheets, he opened his palm and gazed. The star shone white and blue, making the space around him like a cave in an iceberg. He brought it close to his eye. In its depth was the pattern of a snow-flake, the grandest thing he had ever seen. He looked through the flake’s crystal lattice into an ocean of glittering blue- black waves under a sky full of huge galaxies. He heard a remote lulling sound like the sound in a sea-shell, and fell asleep with the star safely clenched in his hand.

He enjoyed it for nearly two weeks, gazing at it each night below the sheets, sometimes seeing the snow-flake, sometimes a flower, jewel, moon or landscape. At first he kept it hidden during the day but soon took to carrying it about with him; the smooth rounded gentle warmth in his pocket gave comfort when he felt insulted or neglected.

At school one afternoon he decided to take a quick look. He was at the back of the classroom in a desk by himself. The teacher was among the boys at the front row and all heads were bowed over books. Quickly he brought out the star and looked. It contained an aloof eye with a cool green pupil which dimmed and trembled as if seen through water.

“What have you there, Cameron?”

He shuddered and shut his hand.

“Marbles are for the playground, not the classroom. You’d better give it to me.”

“I cannae, sir.”

“I don’t tolerate disobedience, Cameron. Give me that thing.”

The boy saw the teacher’s face above him, the mouth opening and shutting under a clipped moustache. Suddenly he knew what to do and put the star in his mouth and swallowed. As the warmth sank toward his heart he felt relaxed and at ease. The teacher’s face moved into the distance. Teacher, classroom, world receded like a rocket into a warm, easy blackness leaving behind a trail of glorious stars, and he was one of them.

One day Ian Nicol, a riveter by trade, started to split in two down the middle. The process began as a bald patch on the back of his head. For a week he kept smearing it with hair restorer, yet it grew bigger, and the surface became curiously puckered and so unpleasant to look upon that at last he went to his doctor. “What is it?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” said the doctor, “but it looks like a face, ha, ha! How do you feel these days?”

Читать дальше