I am convinced I shall go mad. The sense I have of constant high tension in the jaws. The nightmares. And I now have a whole file full of euthanasia cuttings. I keep them locked in the bottom drawer of my desk. A woman in Carlisle has drugged to death a four-year-old boy terminally ill with bone cancer. The judge let her off with a suspended sentence. In Truro a man and wife are fighting because the wife wants their two-year-old comatose daughter taken off an iron lung and the husband doesn’t. He’s divorcing her over the matter and wants custody of the child. She’s contesting it. She says she’s the merciful one. In Dijon, France, a man butchers his new-born mongoloid with a pair of scissors.

I read these articles on the Northern Line. Never more than a couple of brief paragraphs, they nevertheless hold me spellbound the whole journey from Hammersmith to Hendon Central. In Rotherham a nine-year-old boy with severe muscular dystrophy claws his way out of his wheelchair to throw himself from the third floor flat of the council estate where he lives with his unmarried, unemployed mother and alcoholic grandfather. Or was he pushed? And they’re actually bothering to check! Yes, full scale police enquiry. Time, tax money. Is this the public good? Medical evidence shows signs of struggle. Mother says yes but she was trying to hold him back. I miss my station.

Hilary, I think, could never be imagined to have climbed to a window.

On the other hand she can’t simply be switched off.

And I could never kill her with a pair of scissors. I love her.

This happens. I am walking back to the car in the tube-station carpark when I see a hoarding. It says: MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY: We Know The Cause, Now Help Us Find The Cure. What it shows though is three stylised green Plasticine figures. They are children. The two at each side are standing and reaching a hand down to help the third between them who seems to have stumbled and is crouching low. Tripped by the disease. Can they pull him up? Can they rescue their little companion? Buzzing open the car lock with the remote control, I burst into tears. I cover my face. This hopeless, stupid, heart-rending image of human solidarity. I feel so vulnerable. There is a Giro number to send cheques to, but I don’t write it down. The illustration has already convinced me that there is nothing to be done but turn away.

Shirley takes Hilary to church. She has converted though there have been no more dramatic scenes since the confession to my mother. Quietly and conventionally (I almost said sensibly), she goes to church, gets involved in creches, in organising the kind of charitable events I have avoided since I was fifteen. Occasionally ‘church folk’ drop round and make an inhuman effort, maybe twenty minutes, thirty, to give Hilary some attention. Occasionally I find Shirley in what can only be an attitude of prayer, usually by the cot Hilary is now too big for (but she would fall out of a normal bed). So, after all our laughter years ago at Mother’s expense, Shirley has become a Christian. Whatever that really means. But she doesn’t want to talk about it. Nor do I. Just once she says, ‘However obscure, there must be some reason for this, some plan, there has to be. I do believe there has to be a God behind it all.’ Just once I say: ‘You can’t honestly believe we’re guilty and this is the punishment. It doesn’t work like that.’ She says slowly: ‘I know. You’re right. It’s just that sometimes I feel that’s how it was. I make that connection.’ It seems pointless trying to argue the absurdity of this out logically, since sometimes I feel the pull of this explanation myself.

Typical scene. Shirley comes running, says excitedly: ‘Hilary called me Mummy today.’ ‘Great!’ But I know that if the miracle ever happened it will never be repeated. The girl may giggle when you soap her in the bath, she may randomly press those knobs I have provided her with and laugh at the electronic tunes that result, she may even be able to see just a little light and colour, but she certainly never calls her mummy, Mummy.

Dressed up she looks a plain ordinary little girl somebody has tripped up, floundering on her back. On a rare visit, Mrs Harcourt takes a photo of her against a background of Alexandra Palace flowerbeds.

And two hours physiotherapy every single day. It’s a new American method. A trip to Philadelphia to gen up. We, or rather Shirley, bend her joints, roll her head around, knead her muscles. She screams throughout.

Will she ever be able to eat on her own? Even to bring a bottle to her lips? Who knows, but it has become Shirley’s mission I sense. All the more conclusively and engrossingly, because it is a mission that can never be accomplished.

Is this the life she wanted? We wanted? Isn’t it pathetic, creepy, giving so much help to a helpless case? Like my mother with Grandfather, with Mavis. Isn’t it a way of giving up on that other, bigger life we should be living? Shirley is intelligent, attractive, valuable.

‘Is this the life you wanted?’ I ask.

‘It’s the life I’ve been given,’ she says mysteriously.

‘You sound like my mother now.’

‘What’s so bad about that? Your mum’s okay.’

I don’t say it, but I think, At least my mother’s wounded can walk. For some reason I think of the Filipino girl.

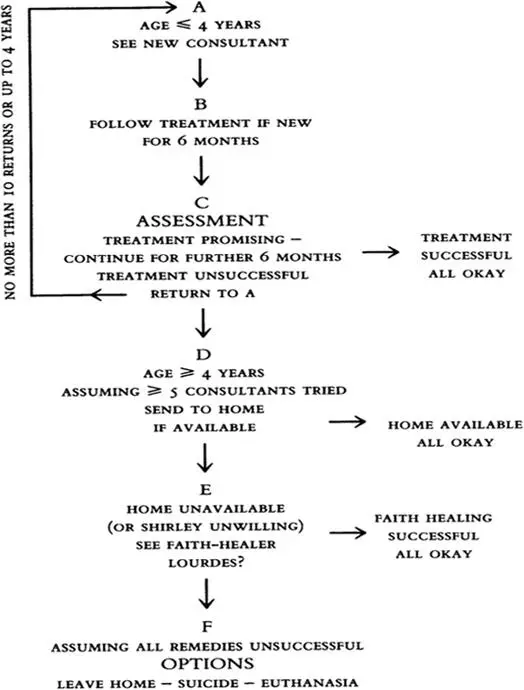

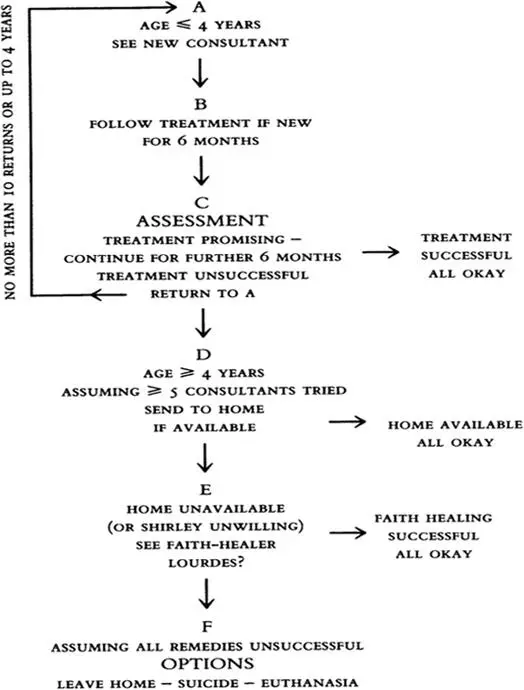

The fact is that although Mother hardly ever comes since that day I told her to leave, Shirley spends anything up to an hour on the phone with her every other day. Talking about me no doubt, and about Hilary’s ‘progress’. Meanwhile, at the office, I draw up the following flow chart:

I find it pretty funny frankly that it took an atheist like me to think of faith-healing. Still, weird things do happen. It would be foolish to pretend otherwise.

‘But you don’t believe in it,’ Shirley protests, laughing.

I remind her that we have tried all the consultants, we have flown to Houston and to Geneva. We have blown upwards of fifteen grand. It’s simply a case of trying to cover every angle. ‘That’s my way.’

She gives me her narrow look. ‘What exactly,’ she asks, ‘is Hilary preventing you from doing in life that you would otherwise like to do? Why keep hunting for a solution you know isn’t there? Come on. Tell me one thing she’s preventing you from doing. Nothing. You see. You can’t think of anything.’

I tell her: ‘Look, Shirley, if Hilary wasn’t here, I’d be happy to have another child. We could adopt one. I do believe we would be happy.’

‘What do you mean, “wasn’t here"?’

She knows perfectly well what I mean. Nevertheless, I say: ‘If she went into a home.’

‘But we’ve been over that a million times. She wouldn’t get any attention. She’d make no progress.’

‘She’s not making any progress as it is.’

‘Yes she is.’

My own inclination is to be honest about these things, however brutal it may seem. All the same, I say:

‘If she were being looked after, you could get a job.’

‘I don’t want a job.’

‘But you must want to get out of the house sometimes. Don’t you?’

‘Of course I do, but I can’t and that’s that, so what’s the point of moaning about it.’

‘You’re denying yourself.’

‘Yes.’

‘For a creature who has no hope, no future.’

She pauses. She bites her lip. ‘Not perhaps in the narrow way you define those concepts.’

‘So how does Shirley Harcourt define them.’

‘I don’t. I just get on with things, that’s life.’

‘Oh, mysterious life again.’

Читать дальше