Tim Parks

Medici Money: Banking, metaphysics and art in fifteenth-century Florence

1348

The plague kills more than a third of the population of Florence

1378

The revolt of the ciompi (woolworkers’ rebellion)

1389

Birth of Cosimo de’ Medici

1397

Cosimo’s father, Giovanni di Bicci, founds the Medici bank in Florence with a branch in Rome

1400

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Naples

1402

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Venice A Medici wool factory opens in Florence

1406

Florence conquers Pisa

1408

A second Medici wool factory opens in Florence

1410

Baldassarre Cossa elected Pope Giovanni XXIII

1416

Birth of Piero de’ Medici (the Gouty)

1420

Death of Baldassarre Cossa; his tomb is commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici

Giovanni di Bicci retires, leaving the bank to his son Cosimo

1424

Milanese army routs the Florentines at Zagonara

1426

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Geneva, later transferred to Lyon

1427

Introduction of the catasto , a form of direct taxation

1429

Death of Giovanni di Bicci

War with Milan over Lucca

1433

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Basle

Medici silk factory opens in Florence

September 7, Cosimo de’ Medici arrested and exiled

1434

September 29, Cosimo recalled to Florence

1435

Giovanni Benci becomes director of the Medici holding

1436

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Ancona

Dome of the Florence Duomo completed

1436–43

Restoration of the Monastery of San Marco financed and directed by Cosimo de’ Medici

1437

Christians in Florence banned from all moneylending practices

1438

Ecumenical conference between leaders of the Byzantine and Roman churches, in Florence

1439

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Bruges

1440

Death of Cosimo’s brother, Lorenzo

1442

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Pisa

1443

Closure of the Ancona and Basle branches of the Medici bank

1446

Branches of the Medici bank open in Avignon and London

1449

Birth of Lorenzo de’ Medici (the Magnificent)

1450

Francesco Sforza conquers Milan with the help of Cosimo de’ Medici

1452

Branch of the Medici bank opens in Milan

1453

Fall of Constantinople

1455

Giovanni Benci, director of the Medici holding, dies and the holding is wound up

1458

Government crisis leads to calling of a parlamento and reinforcement of Medici power

1464

Death of Cosimo

Giovanni Tornabuoni becomes director of the Rome branch of the Medici bank

1465

Tommaso Portinari becomes director of the Bruges branch of the Medici bank

Closure of one Medici wool factory

1466

Piero de’ Medici calls a parlamento and again consolidates Medici power; his son Lorenzo signs a deal with Pope Paul II that gives the bank a monopoly in the alum trade

1469

Death of Piero; his son Lorenzo marries the nobleborn Clarice Orsini; Francesco Sassetti becomes sole director of the Medici bank

1471

Florentine army sacks Volterra

1472

Birth of Piero de’ Medici (the Fatuous)

1476

Assassination of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, duke of Milan, major client of the Medici bank

1477

Death in battle of Charles, duke of Burgundy ( le Téméraire ), major client of the Medici bank

1478

The conspiracy of the Pazzi. Giuliano de’ Medici, Lorenzo’s younger brother, assassinated; Lorenzo survives; war with Rome and Naples ensues

Closure of the Milan and Avignon branches of the Medici bank

1479

December, Lorenzo goes alone to Naples to negotiate a peace with King Ferrante

1480

Turks raid Otranto on the southeast coast of Italy and take 10,000 people as slaves

Closure of the Bruges and London branches of the Medici bank and of the Medici silk factory

1481

Closure of the Venice branch of the Medici bank

1485

Lionetto de’ Rossi, head of the Lyon branch of the bank, recalled to Florence and arrested for fraudulent bankruptcy

1489

Closure of the Pisa branch of the Medici bank

Lorenzo’s second son, Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici, later Pope Leo X, becomes a cardinal at the age of thirteen

1490

Death of Francesco Sassetti

Savonarola begins his sermons on the apocalypse in the Monastery of San Marco

1492

Death of Lorenzo de’ Medici (the Magnificent)

1494

French invasion; flight of Piero de’ Medici (the Fatuous) and collapse of the bank

“With usura,”

wrote Ezra Pound,

“… hath no man a house of good stone

each block cut smooth and well fitting

that design might cover their face.”

By usura, Pound meant usury, or the lending of money at an interest. Not just an exorbitantly high rate of interest, as in the modern usage of the word usury, but any interest at all. He goes on:

“with usura

hath no man a painted paradise on his church wall….

no picture is made to endure nor to live with

but it is made to sell and sell quickly

with usura, sin against nature.”

In the 1920s Pound had come to believe, as many still do, that international banking was a source of great evil. He used the Italian word usura because it was in Italy that the story had begun. During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, a web of credit was spun out across Europe, northward to London, east as far as Constantinople, west to Barcelona, south to Naples and Cyprus. At the heart of this dark web of usura lay Florence. But in the same period, and above all in the century that followed, the Tuscan city also produced some of the finest painting and architecture the world has ever seen. Never had stone blocks been cut more smoothly, never were finer paradises painted on church walls. In the Medici family in particular, the two phenomena — modern banking, matchless art — were intimately linked and even mutually sustaining. Pound, it seems, got it wrong. With usura we have the Renaissance, no less.

This book is a brief reflection on the Medici of the fifteenth century — their bank; their politics; their marriages, slaves, and mistresses; the conspiracies they survived; the houses they built and the artists they patronized. The attempt throughout will be to suggest how much their story has to tell us about the way we experience the relationship between high culture and credit cards today, how far it informs our continuing suspicions with regard to international finance and its dealings with religion and politics.

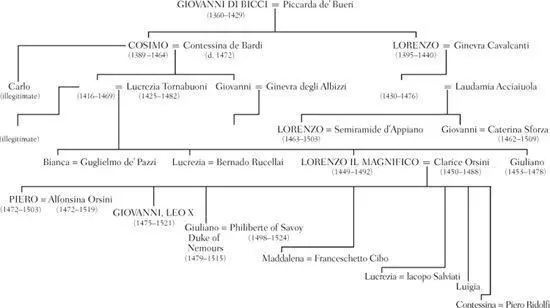

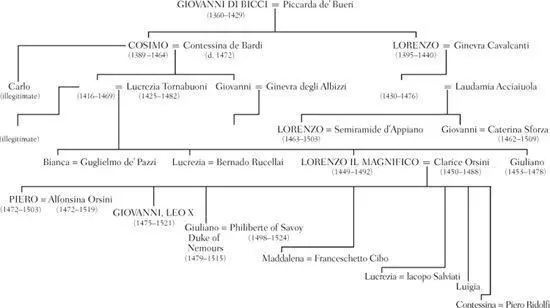

The story is complicated. There are five generations to consider. It’s important to get the main names and dates and the overall trajectory of the thing firmly in the head from the start.

The bank is founded in 1397 and collapses in 1494. Alas, there will be no centenary party. Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici starts it. That is: Giovanni, son of Bicci (inexplicable nickname for Averardo), of the Medici family. Born in 1360, Giovanni is responsible for the bank’s initial expansion and for establishing a particular Medici style. He keeps his head sensibly down among his flourishing account books before departing this life in 1429. “Stay out of the public eye,” he tells his children on his deathbed.

Читать дальше