I didn’t say anything. To be honest, I was intimidated by her beauty — by the way the light attached itself to her, passed through her multi-hued cheeks and neck and hair and sprang from it as if somehow stronger.

After a few minutes I told the VW to put the mood down. He begged me to buy it, but I said no. It wasn’t even an option for me — I just didn’t have the time with me.

“You know what?” the Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass said. “This one’s on the house. Take it.”

The VW’s eyes brightened. “Really?”

“No,” I said to him. Then I turned to her. “That’s very kind. But I can’t let you—”

“I’m not giving it to you,” she said to me. “I’m giving it to him. ”

“Yeah,” the VW said. He put the mood on and his face became very suspicious.

“Take that off,” I said to him. Then I turned back to her. “Really—”

“Too late — done deal,” she said. “He digs it too much for him not to have it.”

“Please,” I said. “That’s just too much. Can I at least give you something for it?” She continued to refuse, but as she did so I saw a very tiny wisp of interest in the glass housing behind her eyebrows. I had to stare at it for a few moments before I was even sure it was interest. But it was.

So I asked her if I could take her to dinner.

She held the question in her mind for a moment, and then looked into her hands. “You don’t need to do that — it’s not that big of a deal.”

“Even so,” I said. “Dinner.”

“No,” she said, clouding.

“I’ll go too,” the VW said.

She stared at me.

“Dinner,” I said again.

The Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass and I went on a few dates — to dinner, to a play that the VW had worked on as an understudy — and then things grew folk; she started spending nights at my place, or I went to hers. I met her mother-of-sand; she came with me when I met the Two Sides of My Mother for breakfast one morning.

We had a lot of faith in each other, and sometimes when we did there was enough light — from the candles, from the moon — for the Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass’s body to catch it, and then I could see myself inside her, see every aspect of that process, the soft and mysterious machine of her body as it moved against mine. It felt like a real relationship; the VW and I stopped going to the Castaway, even!

But these kind of stories — love stories, stories with faith — are apparently not the kind that I was built to book, either that or I haven’t yet learned how to book them. As it turned out, the Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass was too fragile for me; every time we argued or our discussion warmed, her body grew cold and brittle. If she wasn’t careful, she told me, it could crack.

One night we had a very heated argument — she wanted me to move in with her, and I was reluctant to do so because I had to run the Crescent Street apartments — and we couldn’t resolve it. We went to bed angry — she on her side of the bed, me on mine.

That night I dreamt I had all the time in Northampton.

I woke up next to a pile of broken stained glass, and my legs were all cut and pleading. I did all the screaming — the pile of glass was completely silent.

Had I done that? Had I destroyed the Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass, because her glass was fragile and I rolled over in my sleep? Or had she been so cold that she shattered?

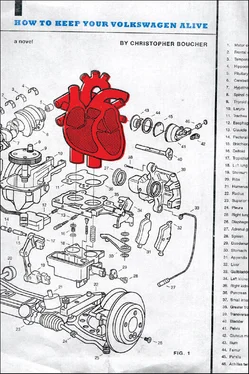

You see what I mean: The story fails, it has a heart attack, it needs something I can’t give it.

I never did get rid of that stained glass, though. A year later, when the VW was really ill, one of his eyes shattered and I used some of the stained glass to repair it. Every time I drove at night from that point on, colors from the Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass’s skin — pinks, blues, greens — were broadcast onto the roads of Northampton.

Years and years later, though, after I’d left it all behind and moved away, I saw a woman who looked exactly like the Lady Made Entirely of Stained Glass. She was dressed in a blue uniform with an orange vest, standing in one of those wooden boxed platforms in the middle of a busy intersection, directing traffic outside a fair. I was so stunned when I saw her that I stepped out into the middle of the traffic and approached her.

She saw me and pointed. “Step back to the curb!” she yelled.

The cars coming towards me slowed down. I held up my hand. “It’s me,” I said.

She put her hands on her glass hips. “Sir, step back to the curb!” she said again.

I kept walking forward.

“Sir!” she bolted.

I smiled as I looked up at her. “I don’t know if I did something wrong that night, or if I just wasn’t able to tell the story right, or what,” I said.

Now we stood in the center of the road and the traffic moved around us. Her look was a fist. “You have me confused with someone else, sir,” she said. “Now, please — go back to the sidewalk.”

“The Volkswagen?” I said. “Northampton, Massachusetts? Remember?”

Her glass hair shone from beneath her blue hat. “Sir, I’m trying to do my job—”

“It is you,” I said.

Her arms were waving madly at the traffic. “I’m not the person you’re looking for,” she said.

But she was. I saw the Memory in her mind: my own image, the pink cloud of fear attached to it.

THE VOLKSWAGEN IS MUSIC II

Sometimes you can make the tune travel, even travel in it. I don’t know if this happened in the town where you grew up (Did it? Type or speak your answer into the power — or just think it, and the book will catch the thought.), but it happens all the time in western Massachusetts. Like I’ve said, these mirkins were everywhere, cupping every aspect of our lives — the weather, our financial status, collective mood and travel conditions. They were in the walls of our homes, our books, our clothes, even! I once had a hell of a pair of musical pants, for example — the notes fit me just right. An ex-girlfriend borrowed them from me, though, and that was the last I saw of them.

In the Volkswagen, incidentally, stories and songs were the exact same thing. I’ve received several deets about this, zoffers coasting keys and rhythm. Dizzyspeak aside, though, I think it’s clear that we’re all always instrumenting — either versing and chorusing, or “His name was Sneaker” and “Later that night I called Edna and asked if we could meet”ing.

Whether you’re esking, fisking or a little of both, though, the practice is only good for so much. Music’ll get you to the store, and maybe from Northampton to Amherst. But can we reach people with it — really reach them? No. How many times, after my father’s disappearance, did I send out songs for him? I can’t even give you a number. For a while there I would leave work in the afternoons, find a place where I could dean — the campus of the old abandoned mental hospital, the Prayer Wheel at UMass — and try and build distance from those old country tunes we once shared. I yelled as loud and as strong as I could in every direction. But what good did it do me? Every tune I sent came back empty and cold. At the end of every story my father was still gone, still dead.

But what did I expect? Songs don’t have hearts —they’re just mindless vessels of notes and beats. This is why 90, 91 and other multitunes are so frightening — they’re nothing but sheer force and character. Hell, most of the time you don’t even hear a melody until you’re in it — until you notice, after some money, that your surroundings have changed, that something has shifted. All of a sudden you look through the windshield and find yourself mid-chorus, or stopped inside a note or unresolved phrase.

Читать дальше