But something kept us together, at least for a time. She was honest and jaw, and I was soft and afraid, and maybe she liked the fact that I would do whatever she told me to. I was happy to oblige in any way I could, even if that meant leaving or curling up to the refrigerator for warmth while she cried out in faith in the bedroom.

Once every few weeks or so, though, the Scientist would open her bed to me and I would climb in, and she would float above me, suspended, and touch me here , and here and here . As she did, I could feel myself getting infected with whatever condition or virus she was carrying at the moment. This explained the pain in my groin. Sometimes I had trouble urinating. For a few weeks I lost all track of time.

But by that time I didn’t even really mind. I was old, and without knowing it I had carved out spaces in my life for each of these conditions. In some subconscious way, I think I wanted them.

That morning, we stood at the counter in Faces until a teenager came to the register. She had lightattoos all over her and her head was completely sized.

I told her that I was there to buy back a name which I had sold to the store years earlier. She punched some keys on the back of a transaction animal — a dog-like creature bred and modified for retail — who sat patiently on the glass countertop, staring at me blankly.

“So,” the girl said. “This was a name you leased to us?”

“I sold it,” I said. “I needed the time for a constant velocity joint for—”

“Sold it when?” The girl’s eyes were gutters.

“Fall, two thousand and three,” I told her.

The girl scrunched up her face. “We usually don’t keep our names for more than four years, even if they don’t sell,” she said. “They go out of style, see?”

“Can you just check for us?” the Scientist said, and she slid her arm around my waist. Her face was lumpy, soft.

The girl typed data into the buttons on the back of the animal. “Hm,” she said, reading the backscreen. “City Life?”

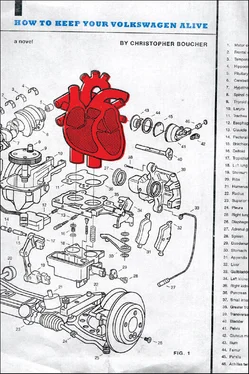

I shook my head. “I had a small child at the time, a Volkswagen?” I said.

“What’s a voke wagon?” the girl asked.

I was getting irritated. “Volkswagen. It was a type of car,” I explained. “He was about—” I tried to think back, “two, two and a half. He was very sick. I needed some quick time, and I’d already sold every moment I could spare.”

“Well, I’m not seeing any other names bought in two thousand three,” she said. “Do you remember the name — what it sounded like?”

“I don’t,” I said.

The girl spoke into her wristmike and asked for a manager, and a minute later one appeared. He looked to be about twenty, and I noticed that his ears had been altered; he’d had small black speakers installed in his eardrums. “Here I am,” he sang to her. “Hi,” he said to us.

I nodded.

“They’re trying to buy back a name that they sold us ten years ago,” the girl said.

“Not quite that long,” I said. “Two thousand three.”

“Hm,” the man said. “We don’t usually … what was the name?”

I winced.

“We’re not sure,” the Scientist explained.

“You don’t remember the name?” he said.

“I don’t. I just remember that it was fall, two thousand three, and that I had my son with me. He was ill that day and he spit up all over the carpets.”

The manager wasn’t really listening to me — he was searching through the database on the backscreen. As he did, the transaction animal shifted in place and itched under his arm, never taking his eyes off of me. These animals frightened me — I had seen footage of them chasing shoplifters down the street, their metal teeth glinting, their bellies bouncing with time.

After another minute the manager shook his head and looked up at me. “I’m not seeing it here,” he said.

“That’s what I told them,” said the girl.

“What does that mean?” I said.

“See, we’re not really in the business of selling names or faces back to their original owners,” he said. “Sometimes, if someone comes in looking to buy back their name and they remember the features, we might still have it or have records of who we sold it to. But that’s pretty rare.”

I leaned on the glass counter, which featured a few of the store’s most expensive faces. “I’ve saved up a lot of time to buy this name back,” I said.

“What if we show you another name?” the manager said.

“I don’t want another name — I want mine.”

A line of people had started to form behind us. “Honey,” the Scientist said.

“I’m really very sorry,” said the manager.

“It was long — it was long!” I said. “Four names, strung together.”

The man pressed his lips together. “That’s not really enough for us to go on,” he said.

I dug my fist against the top of the glass case and the faces beneath it rattled. The transaction animal bristled and showed its teeth. “I have the time now,” I said. “I’ll give you as much as you want.”

The manager didn’t say anything. The look on his face was the yellow lines of Route 47—both had the same hatch marks, the same pattern of wear.

The Scientist excused us and led me outside onto the sidewalk. “It’s just a name,” she said.

The sky was naked and far too wide. “The Other Side of My Mother gave me that name,” I told her.

“Then how can you not remember it? How is that possible?”

“I don’t know,” I yelled into the morning. “But I don’t.”

She took my hands. “Think back,” she said.

“Please,” I huffered. “Don’t try to tell me how to navigate my own memory. It’s like a junkfarm in there, alright? Everything is rotted and picked through.”

She let go of my hands. “Alright.”

“It’s a graveyard,” I said, “filled with the dead and the decomposed.”

“OK,” she whispered. She started walking. “Enough, alright? Can we just go home?”

“This is what I’ve been saying to you,” I said, following her down the sidewalk. “How am I supposed to communicate — to tell you how I feel — if all I have are the bones of words?”

LEAVES OF GRASS

A few weeks after we saw that vested tree at the Castaway, Goshen CityDogs picked up a hospital hitchhiking along Route 9. When they found him he was without words, completely storyless — just a shutdown, abandoned emergency room in critical condition.

The Dogs rushed the hospital to Holyoke Hospital and they fed him stories intravenously. From what I was told, he very well might have died. Four or five days after his arrival, though, his backup generators kicked on and he started talking. The Dogs bedogged him, and when he mentioned Atkin’s Farm they called me. The VW and I drove down to Holyoke and two Dogs met us at the main entrance.

“He’s shown remarkable improvements,” said a SergeantDog, leading me and my son into the elevator. “But I should warn you that he can’t really speak yet.”

“He can’t speak?” the VW said.

“He hasn’t gotten his voice back,” the second Dog told us.

“We’ve been communicating to him through writing, mostly,” said the Sergeant.

The elevator wrapped its arms around us and we were lifted.

“Has he said anything about my father?”

The Sergeant shook his head. “He’s barely awake,” he said. “At first we just thought that he was a drifter, a hitcher traveling down from Ash-field or something. Yesterday, he jotted down the initials ‘AF.’ Robert here suggested that it might mean Atkin’s Farm, and we started to put blues and greens together.”

The elevator released us and we were led past a guard Dog and into the hospital’s hospital room, where I saw a gaunt, ghost-white building with storytubes and morning cables attached to his roof and every window. He was hardly even a Memory of the starched, orderlied Cooley-Dickinson that I remember.

Читать дальше